Memory, mourning, and melancholia figure prominently in the films of Dang Nhat Minh, Vietnam’s national film director and scriptwriter. Born in Hue in 1938, Dang studied in the Soviet Union where he was introduced to filmmaking (Cohen, 2001). His state-funded oeuvre – including When the Tenth Month Comes (1984), Nostalgia for the Countryside (1995), The Girl of the River (1987), and Don’t Burn (2009) – typically promotes national communist ideology, honoring war heroes and celebrating collective social struggles for national well-being. The focus of this paper is Dang’s 1999 film, The House of Guava, which breaks rank with this oeuvre (and its sponsors), deviating from the party line (Bradley, 2001: 201-216). Entitled Mùa ỏ̂i (literally “The Season of Guava”), 1 the film is an adaptation of Dang’s own short story, The Old House (Lam 2013: 155). Dang’s film took two years to clear the red tape before filming could begin and has not been screened in Vietnam since its release in 1999 (Cohen, 2000).

The House of Guava narrates the story of a French-educated Vietnamese lawyer and his Francophile middle-class family over a period of great historical rupture: 1954 to the late 1980s. The attorney designed his own modern villa and had it built in Hanoi. The narrative centers on the attorney’s three children. Hoa, the middle child, falls while picking guavas from the tree planted by the family in their garden, and injures his head. When we pick up the story, Hoa is fifty years old. His eldest brother, Han, has emigrated to Germany and Thuy, Hoa’s younger sister, is his caregiver. Present and past collide in suspended animation: due to his head injury, Hoa’s memories and intellect are congealed in time, resisting diminishment even after the family is expelled and the property confiscated in land reforms that swept the north between 1959 and 1960 (Cohen, 2000).

I argue that Dang’s daring counter-narrative to the communist legend of collective ownership, and his filmic representation of private memories, together point up a productive fissure between national and private memories. By providing us with an alternative theatre of memory, The House of Guava highlights the wide-scale erasure of private memory and questions the tandem legitimization of the collective history and memory of the Nation, and by extension, the political regime behind that “memory,” new or old. I further demonstrate how The House of Guava magnifies the inhumanity of the Communist regime by focusing not only on the confiscation of a middle class family’s property, but also on the attempted appropriation of memory to make room for an equally corrupt and competing communist ideology of social equality and collectivity. I analyze Dang’s innovative filmic language in narrating and providing visual representations to this complex story of changing political regimes of memories through three core stages: forgetting; erasure; and deracination. Finally, I demonstrate how in Dang’s film, memory is embodied as experience.

The House of Guava opens with a 35mm close-up of a pair of feet in sandals tiptoeing along the fence of a modern villa in the city of Hanoi

This scene is followed by a distance shot of the fence from the villa’s interior. We see Hoa’s face and eyes peeping through an opening in the fence to look at a tall guava tree planted by his father in his former home. The present residents are a high-ranking government official; his spoiled daughter, Loan, a university student, and their elderly female servant who cooks and cleans for them. The rest of the family stays in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon). The fifty-year-old Hoa climbs the fence in order to revisit his guava tree, but is caught trespassing, and ends up at the police station. His sister Thuy bails him out by signing a paper confirming that Hoa is mentally ill.

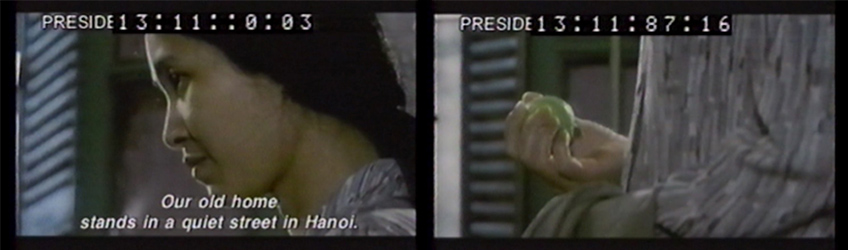

A poignant scene unfolds, and we soon learn why Hoa lives in his memories. Thuy brings Hoa home from the police station on the back of her bicycle. She helps him undress as though he were a baby, and orders him to take a shower. While emptying the pockets of his soiled trousers, she finds a green guava fruit that he has plucked from the tree that their father planted. As she holds it in the palm of her hand, the guava’s weight and tactile presence evokes Thuy’s memory of what happened to her family and especially what precipitated Hoa’s mental condition (Figs. 2 and 3).

Thuy now narrates their family history and Hoa’s life-story as voiceover, against flashback images of the house as it was furnished and inhabited thirty years ago.

“Our old home stands in a quiet street in Hanoi. Daddy had it built to his own design. It’s over thirty years since we moved out. All I remember of it is that accursed guava tree that wrecked the life of my brother, Hoa. One day, he fell out of it and hurt his head so badly that he went on growing physically, but not mentally. When daddy died, our elder brother had to emigrate to Germany. He asked me to take care of Hoa. He said to me, ‘Dad gave all his love to the unluckiest one.’ That’s what I am doing. He is two years older than me, but to me, he will always be my thirteen-year-old kid brother.”

Hoa is now fifty, his middle-aged body housing a teen-age mind. Intellectually/cognitively disabled, he contributes to the collective ideal of a socialist society through his work as a model for the art school in Hanoi. In painting and drawing classes, Hoa often poses as a young heroic soldier fighting at the front, and is thus simultaneously conscripted by the state into the larger national projects of modern art and propaganda art (Taylor, 2001: 109-134; Buchanan, 1999). Neighbors capitalize on Hoa’s naïveté and kindness, taking advantage of his labor. A model of filial piety whose time-frozen mind has presumably remained impervious to the very anti-Confucian, anti-ancestral propaganda of whose project he is now part, Hoa always remembers the anniversary of their parents’ death and performs rituals accordingly. In brief, Hoa behaves like a good-natured, innocent thirteen-year-old kid. Hoa’s mind and memories belong to a life and time long gone, a time under a previous political regime while his skinny, aging body belongs to the labor force of the current regime that is in keeping with the socialist ideology. Hoa’s mind and body signify a lost time.

Another poetic scene from the film shows how a time and place not only haunt the characters, but also embody memory. Cultural geographer Yi Fu Tuan posits that a place is often associated with security while a space signifies freedom and thus adventure into the unknown (Tuan 1977: 3). Indeed, this familiar place called home in its physical or imaginary sense compares both culturally and symbolically to the space of a mother’s womb; home is where the child is protected.

“Home” further triggers Hoa’s memories of his childhood when Loan, the daughter of the new residents, establishes a connection with Hoa, inviting him back to visit despite his intrusion. We see a close-up shot of Hoa’s and Loan’s feet as they climb the stairs together and at times, they step on their own shadows. Pairs of feet walking become leitmotifs that Dang uses not only to link the narrative thread in the film, but also to make visible the centrality of the human body as sites/sights where memories reside, especially repressed memories (Fig. 4).

The tracing and retracing of one’s footsteps or footprints suggest a return to the place/space where happy and traumatic memories simultaneously reside—we witness the embodiment and experience of muscle memory.

Loan acts as if she is the curator of a museum of memories; she opens the door to each of the upper floor rooms for Hoa. As soon as he sees the bedroom, the haunted space evokes the sadness of his mother’s death when he was a young boy. Loan then opens the door to the living room, and the sound of the young Thuy’s piano practice comes to Hoa. He also remembers how he used a pencil to trace his mother’s shadow on one of the white walls in the room (Fig. 5).

The pencil portrait of his mother has long been painted over by the new owner, but like the traces of his footsteps and the footprints of his old home and the city of Hanoi, the sketch of his mother’s portrait remains indelibly inscribed in his memory. Moreover, the muscles in his body have their own memories of places and spaces that his body has visited and experienced. Hoa touches the white wall with his hand (Fig. 6).

This tactility and texture of memory reminds us of his sister, Thuy holding a guava fruit in the palm of her hand. Through such gestures memory, whether trod underfoot or literally handed down, becomes a profoundly embodied experience in Dang’s film.

Hoa’s embodied memories of childhood in his old home, like the guava tree and its fruits, nurture and sustain Hoa’s daily life. However, not everyone understands these needs or supports the possibility of living one’s life in the past. Hoa’s brother in-law remarks: “The crazy thing about Hoa is that he lives in his memories.” When Thuy responds: “What’s crazy about that?” we see that her empathy for Hoa stems from her own repression of memories. By encouraging her to remember, Thuy enables Hoa to make sense of her family’s history.

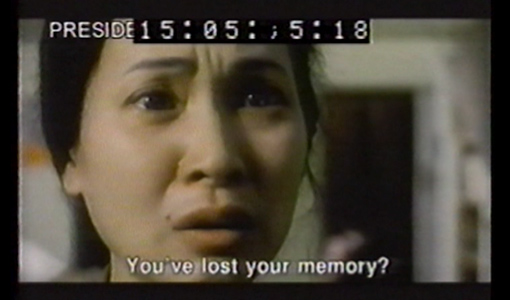

Loan’s father, a senior Communist party official, judges Hoa most harshly of all. When Loan invites Hoa to stay in a room of her home while her father is away on business, he accuses Hoa of bringing prostitutes into the house on his return, and has him committed to a psychiatric hospital. Hoa is medicated to suppress his impulse to remember and to speak. When Thuy brings Hoa home from hospital, and asks whether he remembers their old home, Hoa replies: “What old home?” Thuy panics and runs to a nearby market to buy guava fruits to stimulate Hoa’s childhood memories, but her attempts are futile (Fig. 7).

Thuy breaks down in tears and cries, ”My gods, you have lost your memory!” (Fig. 8)

Conclusion

The House of Guava explicitly critiques the land reform implemented by the Communist government of North Vietnam in the 1950s by highlighting both the displacement of upper and middle class families in Hanoi, and the erasure of their descendants’ memories of genealogy and ties to geographical and cultural place. Dang’s film also addresses how this deliberate erasure of memories has kept the children of Communist party leaders ignorant and thus oblivious to the violent events that took place in houses that they occupy. For example, after having heard Hoa’s biography from Thuy, the young Loan replies, “What a strange story; I can’t figure it out.” Is this learned ignorance? Willful ignorance? We are left to guess, but an altercation between Loan and her father at the end of the film suggests that it is she—the daughter of a senior Communist official—who is now the defender and curator of Hoa’s memories of his childhood.

Loan: “He used to live here. He has memories of it.”

Father: “Memories? What does that mean?”

Loan: “How can I explain? Things you never forget.”

Father: “He’s insane, you mean. Memories! Memories!”

Loan: “He’s not insane!”

Finally, Dang’s film exposes the corruption and hypocrisy of senior officials in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam whose chauffeurs drive them around in fancy cars, and who live in villas confiscated from the elites of the ancien regime and staffed by servants and cooks. In Dang’s film, these hypocritical officials and their children are represented as parasites. Two scenes from the film capture this metaphor succinctly. First, when Hoa peeps through the fence, Loan is shown reclining on her chair reading, with a plate of guava fruit near her feet. There follows a close-up shot of Loan chewing on a guava fruit picked from the tree planted by Hoa’s father (Figs. 9 and 10).

A second scene shows Hoa catching a caterpillar eating away the leaves of his guava tree; Hoa kills it by smashing it with his foot (Fig. 11).

Both scenes show the occupants of the house and elite members of the new regime as parasites who devour and spoil the fruits of others’ labors. This is not only a paradise of the blind, but also a parasites’ paradise.

The film concludes with the violent sound of an electric chain saw chopping down the guava tree (Fig. 12).

Loan does her best to protect the guava tree, but fails. Her family moves away, and the house is rented to a foreign company. Doi Moi is here, and Vietnam has begun to welcome foreign investment; we are witness to the violence implicit in this slow transition from a socialist to a free market economy.

Dang’s film offers a politically subversive and powerful critique of the inhumane treatment of educated elites by a new regime whose cruelty extends beyond a deliberate erasure of memories, to the denial, deracination, and physical destruction of the family tree. The lingering poignancy of The House of Guava resonates with similar situations elsewhere in Southeast Asia, where regime change wreaks trauma on the writing, rewriting, and representations of history and memory, and on the body.

Boreth Ly

Associate Professor, Department of History of Art and Visual Culture

University of California, Santa Cruz

Issue 20, Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, September 2016

Notes:

- I would like to thank Luong Tran, Hung Meng Nguyen, Thi Nguyen, Ellen Takata, Resmeiy Chhuy, Mirren Theiding and Penny Edwards. An additional thank you to Dang Nhat Minh for granting permission to reproduce the film stills in this article. ↩