Major comic publisher Elex Media Komputindo (EMK) publishes 52 translated Japanese comics compared to just 1 locally produced comic per month. M&C, another major comic company admits that 70% of what they publish are translated Japanese works (Kuslum, 2007). The popularity of translated Japanese comics is also supported by their cross media strategies. Their presence creates an awareness of local comics amongst Indonesians (Ahmad, et.al, 2005: 1, 2006: 5, 44–45; Darmawan, 2005). The narrative of Japanese comics as a threat to Indonesian comics appears in the national newspaper Kompas (26 November 2007); and in comics exhibitions such as DI:Y (Special Region: Yourself) Comic Exposition (2007) and Indonesian Comics History Exhibition (2011).

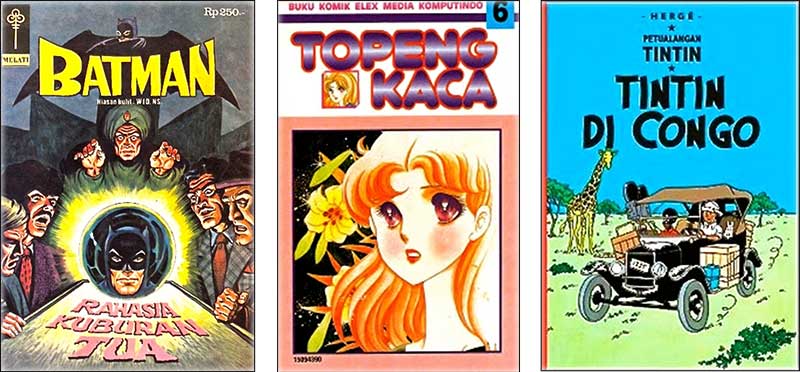

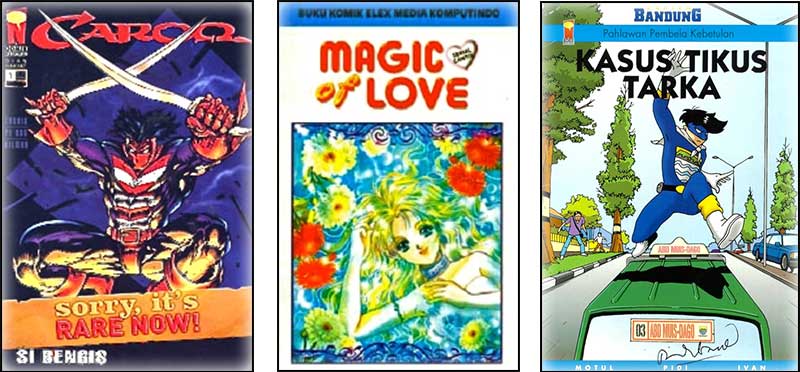

Readers have become aware of the nuances that separate local comics and how foreign comics differ from each other. A reason why readers have knowledge of these nuances is through the introduction of foreign comics publications at different periods. Superhero comics from America were imported in the 1950s, while the adventure comics of Tintin and Asterix from Europe were first seen in the 1970s. Japanese comics entered the market at the end of the 1980s. Another reason would be that the foreign comics had distinctive visuals. The combination of the two factors prompts the classification of comics based on geopolitical territory as seen in several publications (Ahmad et.al. 2005, 2006; Giftanina, 2012; Darmawan, 2005), and in the practice of comics publishing. Readers, publishers, and artists refer to local comics as being drawn with foreign styles (gaya).

This style (“gaya” in the Indonesian language) refers to an abstract comics convention. In Indonesia comics discussion, gaya refers to character drawing, panel layout, or theme ― elements that are related to visual stereotypes. Prominent examples include: the large-eyes characters in Japanese comics (manga), realistic drawn American superhero comics, and the ligne claire drawn in European comics (Giftanina, 2012; Ahmad et.al, 2005, 2006: 109). Publishers can direct their artists to draw in a certain gaya. 1 Some publishers in Indonesia clearly state in their submission guidelines that they reject Japanese styled comics (e.g.: Terrant Comics) (cited in Darmawan, 2005: 261), while some accept all styles (e.g.: Makko). An editor can blatantly introduce a gaya on its back cover. One example is “Mat Jagung” (Dahana, 2009), where it stated that it was drawn with European gaya. 2

Identifying a comic’s style is practical because it can easily categorize comics readers (Ahmad et.al, 2006: 83–87). Hafiz Ahmad, Alvanov Zpalanzani, and Beny Maulana wrote in their book Histeria! Komikita (2006) on the segmentation of readers through their different preferences (Ahmad etl.al, 2006: 93–100). They stated that readers were reluctant to read comics in other gaya (Ahmad et.al, 2006: 93), thus Japanese comics readers could only be familiarized with Indonesian comics in Japanese gaya. Ahmad, et.al made a comment that style preferences were distinctive on different generations (Ahmad.et.al, 2006: 94). Since the 1940s and 1950s, imported American comics entered and started a similar boom for Indonesian superhero comics, such as Garuda Putih, Puteri Bintang, and Sri Asih (Ahmad.et.al, 2006:94). 3 The European comics entered before the Japanese wave in 1980s, when translated Japanese comics entered with their animations. Thus, each generation received influences from different comic cultures (Ahmad.et.al, 2006: 94). When these readers became writers of their own comics, they mimic the gaya they were most familiar with. They also submitted their comics to publishers that were open to gaya they were drawing. Because of this, gaya has become the comfortable standard to identify an aesthetic and preference in comics reading, writing, and publishing.

As a reader, I have embraced notions of different gaya intuitively. The descriptions by Giftanina (2012) and Ahmad, et.al (2006) cited above are as elaborate as any other common attempt to explain different gaya in discussion. 4 However, as a comic scholar, I still find it difficult to find a rationale behind the need for gaya classification by geopolitical labels. The classification has invited many controversies such as, the quest of finding a unique and different gaya for Indonesia. Giftanina (2012) provides a hypothesis that unique Indonesian aesthetics could contribute to the map of comic styles globally, while there are other measures such as those taken by MKI and another publisher (Terrant Comics) to isolate the recently popular Japanese style in effort to create a unique Indonesian gaya.

This paper will not make such claim; instead, it will expand the discussions of Giftanina (2012) and Ahmad.et.al (2006) on the problems and potential behind this classification of gaya. By discussing the Indonesian comics, Wanara, I would like to explore the blurring boundaries of the different gaya in Indonesia.

WANARA

Wanara was written and drawn by Sweta Kartika. Since May 2011, Sweta published his comic monthly online: Makko

Makko is a publisher that accepts submissions from all styles.

“We do not endorse into a single comic style. Comic does not have to be drawn in specific styles such as manga, US, Europe, manhwa, manhua, et cetera. We have our own specific standard to select comic that we are going to hire” (Makko.Co. Comic Publishing Company).

The guidelines recognize different comics styles in Indonesia and have never labeled the comics they publish with any specific style. Thus, one can start reading Wanara without assuming a foreign style is attached to their works.

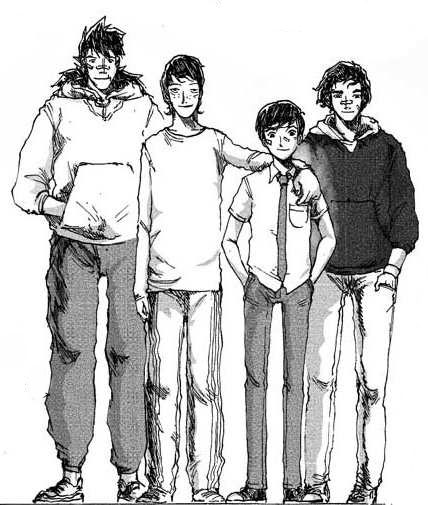

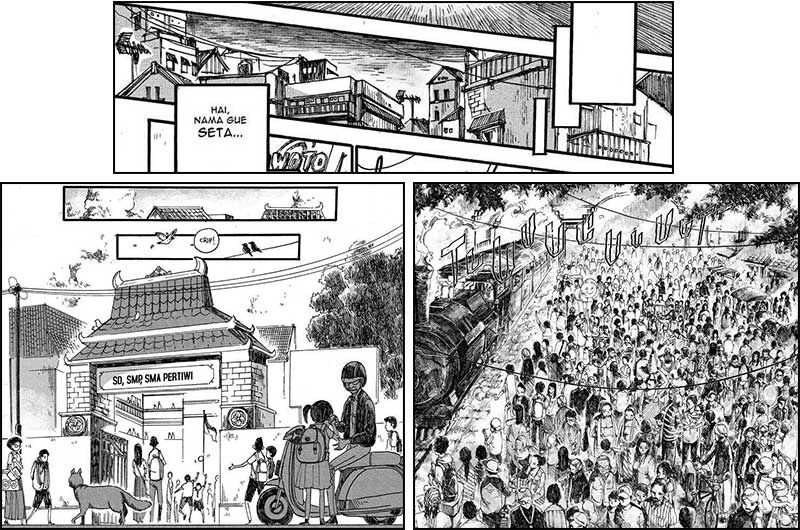

Wanara featured the adventures of an ordinary high school student named Seta. Seta is a martial arts practitioner and superhero enthusiast, who tries to save a veteran superhero. This elderly superhero, Panca, was kidnapped by an organization called P.CO, led by Panda. Brata, a disciple of Panca, was also on his way to rescue him. Seta and Brata met other young heroes with the same goals and created a new league of superheroes, Wanara. Wanara continued the legacy of previous generation of heroes to defeat the evil.

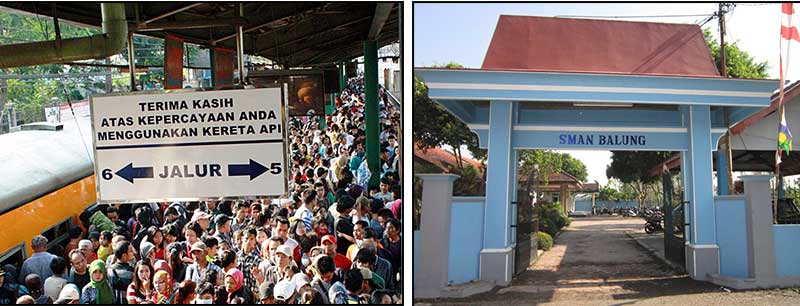

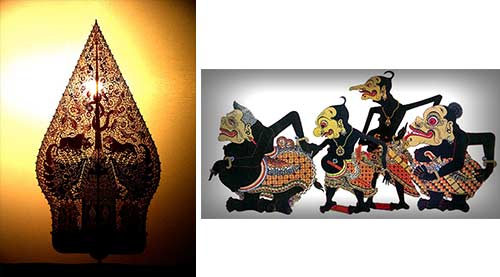

Wanara is set in modern day urban Indonesia. As a high school student, Seta wore a government-issued uniform or normal clothes any teenager would wear. The landscape was rooted in Indonesian reality with a touch of science fiction through the presence of anthropomorphic animals, inhumanly shaped characters, futuristic technology, and supernatural actions. This landscape was contrasted with the depiction of traditional Javanese and Sanskrit elements.

Examples of such were the use of contemporary Javanese royalties in the storyline, and illustrations of ancient Javanese temples and designs. They also used the keraton, royal houses of Yogyakarta.

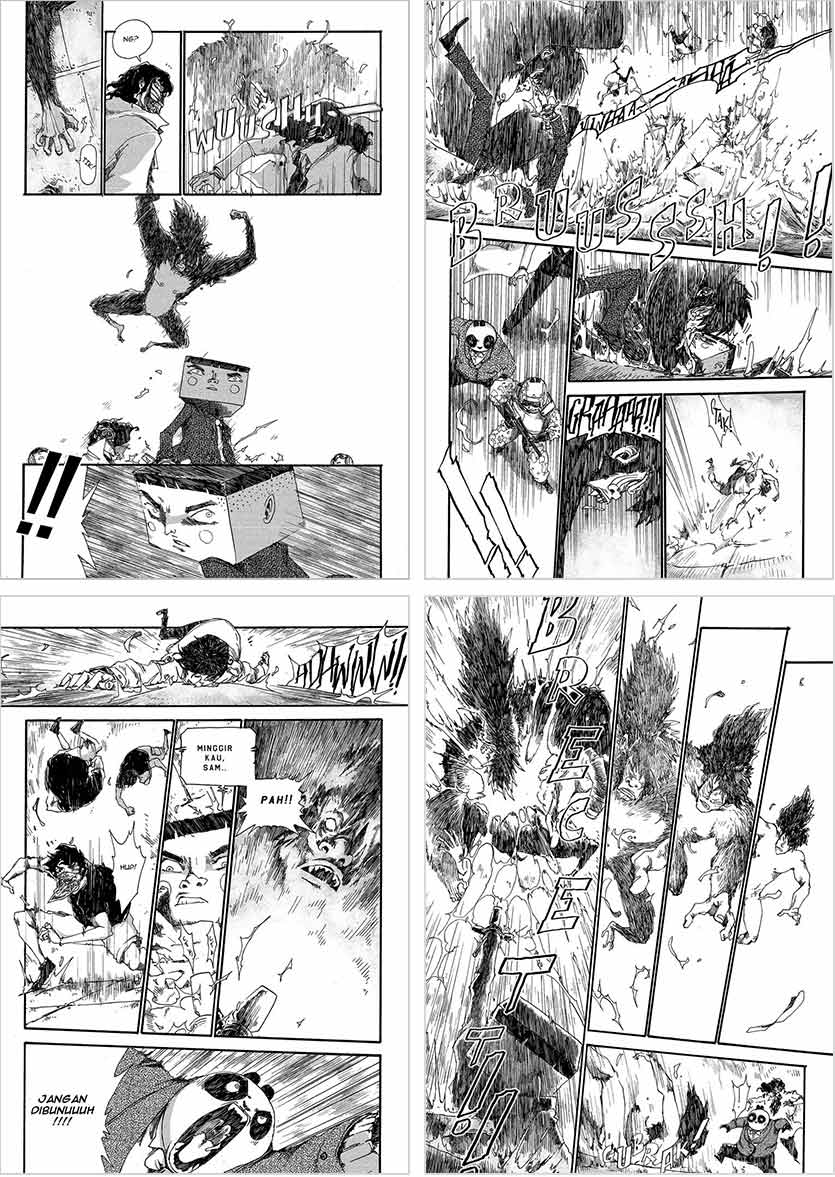

Readers enjoy Wanara’s interesting story packed with thrilling action. The action scenes are vividly depicted through a series of consecutive panels.

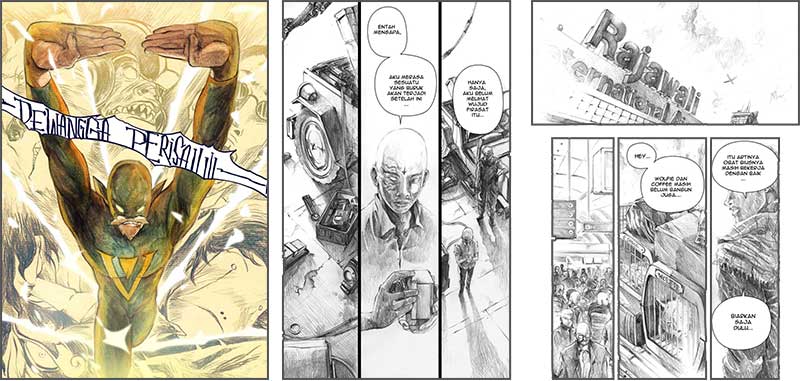

These four pages not only consisted of panels that detail one action after the next, but also bring to life the speed of the action taking place. The vertical lines represent the velocity of falling and diagonal lines behind Mr. Q represent Monster moving in superhuman haste. Reading through the panels I thought, “Wanara was drawn with a Japanese gaya”. Despite the realistic depiction of an Indonesian school environment and the constant reminder of the Javanese culture (every Wanara issue cover is illustrated with a mascot drawn with Javanese traditional decorations), the paneling and the movements in the comic immediately associates Wanara with Japanese gaya.

Even though Wanara was not labeled as a Japanese styled by the publisher, the familiarity with the Japanese style did not surprise me. I realized that Wanara had visual elements in common with Japanese comics such as the compositions of un-uniformed panels showing detailed actions that are common in shōnen comics—the shape of speech bubbles, the usage of onomatopoeia (the formation of a word from a sound associated with what is named), the black and white drawings with screentones and the two different bodies of the same character (the deformed bodies of characters that appears in comedic situations).

Despite the consistency with Japanese visual stereotypes, interspersed with these are several color pages which accentuate actions scenes:

The drawings in these occasions were more realistic with symmetrical panels and dramatic angles. On these occasions, the notion of Wanara as a Japanese style comic to the gaya of American superheroes comics.

My need to associate Indonesian comics with particular gaya reflects how this classification has been ingrained in my mind. The change of gaya in Wanara proved the proficiency of Kartika’s drawing skill so that he could manage to master different gaya. It was also a vexing reminder of how easy it was to associate particular images to geopolitical gaya which were prevalent in Indonesian comics.

Wanara had a distinctive depiction of two generations of superheroes: the older generations and the younger generations. The import of European and Japanese genres in 1980s introduced the concept of non-muscular body types participating in action-packed scenes (keseharian, Ahmad, et.al., 2005: 18, 58). The older generation was drawn in the American style, while the younger generation were depicted with smaller frames, lacking costumes, and only wore normal clothes to battle. The presence of two generations represented the different comic cultures prominent in the two generations.

Through the reading of this work, Wanara had the potential to reconcile the different comic aesthetics present in Indonesian comics.

The Limitations and Potential of Geopolitical Classification through Wanara

The presence of foreign comics is massive that geopolitical classification has become a standard. This classification started some extreme tendencies to exclude certain gaya in order to find an exclusive aesthetic domain (such as Terrant comics policy to prohibit submission in Japanese gaya). The main problem of geopolitical classification lies in its exclusivity. It implies that a comic drawn, written, and published in Indonesia but drawn with foreign styles could not be considered Indonesian. However, Sweta Kartika broke those rules by writing Wanara.

Through Wanara, a comics reader recognizes as Japanese comics, interspersed with elements that is associated with other foreign gaya. Wanara showed that one comic never can exclusively belong to one gaya; thus blurring the distinctions of different gaya. This classification hampers the development of future works that could combine different gaya. It limits the creativity of an author from borrowing, and combining the creations of their peers. Wanara is a clear example of the fluidity of comic aesthetics, that gaya have potential to expand beyond any definition. Thus, in order to expand the aesthetics of comics, nothing should be isolated by rigid classification nor definition.

However, the notion of gaya should not be dismissed right away. In the case of Indonesia, the awareness of gaya is triggered by a history of foreign comics influences, which created trends of different aesthetics. Seno Gumira Ajidarma (2011) showed that Indonesian comic Panji Tengkorak was remade three times with different aesthetics. (1965, 1985, 1996). The same example is seen from Wanara, where there is an incorporation of two different visual gaya from two different comic generations.

The standard gaya term in Indonesian comics publication shows the importance of recognizing the presence and practicality of categorizing different aesthetics in Indonesia in the technicalities of publication, for instance submission guidelines. Researchers should not only address how problematic the notion is, but should address its function and potential. Scholars must be aware of any political implications in the question of identity in their discussions; and how it can disengage the fluidity of comics aesthetics.

Febriani Sihombing

Ph.D. Candidate

Graduate School of Tohoku University

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 16 (September 2014) Comics in Southeast Asia: Social and Political Interpretations

References

Ahmad, Hafiz, Alvanov Zpalanzani, and Beni Maulana. 2005. Martabak: Keliling Komik Dunia. (Jakarta: Elex Media Komputindo).

_____2006. Martabak: Histeria! Komikita. (Jakarta: Elex Media Komputindo).

Ajidarma, Seno Gumira. 2011. Panji Tengkorak: Kebudayaan dalam Perbinacangan. (Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia).

Bonneff, Marcel. 1998. Komik Indonesia. Jakarta: KPG (Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia).

Darmawan, Hikmat. 2005. Dari Gatotkaca Hingga Batman. (Yogyakarta: Orakel).

Dwinanda, Reiny. 2007. “’Gerilya’ Komik Indonesia” in Republika, March 11th, 2007

Giftanina, Nanda. 2012. Hilangnya Identitas Kultural dalam Perkembangan Komik Lokal Indonesia

Indonesia Today. 2012. “Dunia Perbukuan Indonesia di Ujung Tanduk” in Indonesia Today, June 29th, 2011

Kartika, Sweta. 2011 ~ 2013. Wanara

Kuslum, Umi. 2007. “Masih dalam Dekapan “Manga”” in Kompas, November 26th, 2007.

McCloud, Scott. 1993. Understanding Comics. (New York: Harper Perennial)

_____. 2001. Memahami Komik [Indonesian translation of McCloud 1993]. Jakarta: KPG (Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia).

Interview with Seven Art Land Comic Studio artist, Rie, held in Cilandak (September 18, 2010).

Notes:

- Interview with Indonesian comics artist Rie, September 18th, 2010. ↩

- “Mat Jagung is a role model that is worthy of praise. This anti-corruption themed comic strip with European comics style are successfully attracts readers every week.” (Dahana, 2009) ↩

- The discussion on how foreign comics made an influence in the creation of Indonesian comics starts at the first significant publication on Indonesian comics Komik Indonesia (1998) based on comic scholar Marcel Bonneff’s publication on Indonesian comics Les Bandes Dessinnes Indonesiennes (1976). In the dissertation, Bonneff stated that the first genres of Indonesian comics received influences on many Indonesian comics. For example: the martial arts genre (silat) was based on the Chinese comics (sic.) popular at the 1960s in Indonesia (Bonneff, 1998: 24). ↩

- Author and journalist Seno Gumira Ajidarma, in his dissertation of Indonesian comics PanjiTengkorak (2011) writes the three different aesthetics in Indonesia through the three remakes of classic comics Panji Tengkorak (1968, 1985, 1996). His writings are the only publication that has never attempt to classify the aesthetics in geopolitical classification of gaya as commonly discussed elsewhere in Indonesia. Through the visual differences of threePanji Tengkorak, he stated that the reproduction of culture are construction of the ideology popular of each time. Author Hikmat Darmawan also attempts to discuss on foreign comics, including their ideological and cultural journal in Dari Gatotkaca hingga Batman (2005), and their influences on Indonesia. He concludes with encouraging Indonesia to create its own unique comics icon and production model. These two publications are not commonly known outside the comics scholars in Indonesia. Meanwhile, Ahmad.et.al’s is a popular book can be obtained in major bookstores. ↩