Sino-Burmese Relations During the Early Period of Diplomatic Relations (1950-1953)

Burma established diplomatic relations with China on June 8, 1950, making it the first non-socialist country to recognize the People’s Republic of China (PRC). However, bilateral relations developed slowly during the early period, with the two sides holding a skeptical attitude towards each other. Burmese leaders, having just won independence and consumed with strong nationalism, were fearful of the new China. A report submitted by the Chinese Embassy in Burma to China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs related: “The Burmese government treated our National Day celebrations here in a perfunctory manner and tried to impede our efforts, because they knew we would take this opportunity to expand our political influence, although they could not just stop them. But, for example, when we were consulting with them about the Burmese guests to be invited for the upcoming reception, they refused to give us the list of names and carefully studied the names of people who were going to be present. Difficulties also occurred with the selection of the venue of the celebration and the decoration work on the site.… They wanted very much to smell out our intentions through these celebrations.” 1

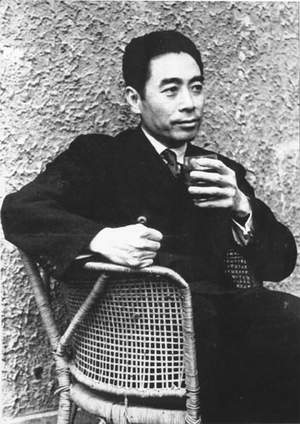

Burmese leaders also expressed openly Burma’s suspicion and fear of China on several occasions. Burmese Prime Minister U Nu once said, “I should admit, prior to Premier Zhou Enlai’s visit to Rangoon, that there had been mutual distrust between our two peoples. On the Burmese side, a considerable number of people were fearful that the PRC would set up stumbling blocks for the Burmese government, while on the Chinese side there had been serious doubt about whether Burma was a truly independent country or a pawn of the UK or the US.” 2 In 1954, Sao Shwe Thaik, head of the upper house of the Burmese parliament, said to the visiting Chinese premier Zhou Enlai, “people in the northern part of Burma are disturbed by the presence of Kuomintang (KMT) troops, fearful that the PRC government and the KMT should have military clashes in Burma.… As a small country, Burma has to maintain friendly relations with its neighbors.” 3 In December, 1957, during his meeting with Mao Zedong, U Kyaw Nyein, Burmese Deputy Prime Minister, admitted that, “prior to Prime Minister U Nu’s visit to China and his meeting with Chairman Mao, Burma was, indeed, afraid of China, because Burma is a small country while China is a big one.” 4

After it became independent, Burma pursued a foreign policy of neutrality. In the early years after the establishment of diplomatic relations with China, Burma was very cautious, wanting neither to offend the Western bloc by having close contacts with China, nor to displease China by having an intimate relationship with the West. One declassified Ministry of Foreign Affairs document analyzed Burmese foreign policy this way: On the one hand, as a close neighbor, “Burma does not want to be an enemy of China by turning to the imperialist camp for shelter. If it had conflict with imperialist powers, it would like to look to China and the Soviet Union for help.” On the other hand, “although the ruling class of Burma has a strong desire to be independent, it has unbreakable connections with the imperialist powers, depending on them to a large extent. Therefore, diplomatically, Burma is still unable to shake off the influence of the West.” 5

The lukewarm relationship between Burma and China had clear manifestations prior to Zhou Enlai’s visit in 1954. For example, meeting with the Chinese Ambassador to Burma, Yao Zhongming, the Burmese foreign minister said it was not appropriate for the Ambassador to make remarks opposing US imperialism when addressing local overseas Chinese gatherings and suggested that Yao be prudent in his wording so as to avoid trouble. 6

On October 18, 1951, Yunnan Daily published “The Burmese Struggle for World Peace,” by Thakin Lwin, Chairman of Burma Conference to Defend World Peace. This article asserted that “US imperialism, under the glorious name of ‘economic aid,’ expanded and constructed airports all over Burma” and that “the US tries to use Burma to conduct sabotaging activities against the People’s Republic of China, the vanguard in fighting imperialism.” The Burmese side, which denied all this and reiterated its neutral and foreign policy of good neighborliness, 7 demanded that the Chinese foreign ministry publish an explanatory article in the Yunnan Daily to clarify the incorrect message. 8

The alienation between China and Burma in the early years after the establishment of diplomatic ties can be attributed to the following: first, unfamiliarity and mutual suspicion between the new leadership of the two countries; second, the overseas Chinese problem; third, the unsettled border issue; fourth, KMT troops in the Golden Triangle area in the north of Burma; fifth, geopolitical and historical reasons; and sixth, the Cold War. It was only after Zhou Enlai’s visit in June 1954, when the two countries initiated the Five Principles of “peaceful coexistence,” that relations between them developed rapidly. Later, the two sides held consultations and exchanged views on issues of common concern. G. William Skinner, an American scholar, believed that after the Second World War, China and Southeast Asian countries had to address four issues concerning the overseas Chinese: the dominant role of overseas Chinese in the non-agricultural sector of Southeast Asia’s economies; the education of overseas Chinese; the legal identity and dual nationalities of overseas Chinese; and the political integration of overseas Chinese into the newly independent Southeast Asian countries. 9 In the 1950s, in order to ease Burma’s concern and suspicion about the overseas Chinese, the Chinese government made efforts mainly in the areas Skinner outlined.

The Nationality of Overseas Chinese

After World War II, with the founding of the PRC, the independence of Southeast Asian countries, and the beginning the Cold War, China, in developing its diplomatic ties, had to address the unavoidable issue of defining the nationality of overseas Chinese residing in these countries. In the context of the Cold War, the overseas Chinese in the emerging nationalist countries were victimized by nationalist sentiments and ideological inclinations. The Southeast Asian countries judged the loyalty of the overseas Chinese by their nationality, especially the dual nationalities held by some. It was for this reason that the Chinese government tried to dispel Southeast Asian countries’ suspicion that the overseas Chinese were being used as a “fifth column” by China. In the early 1950s, there were 350,000 overseas Chinese in Burma. In light of the Nationality Laws of the two countries, 260,000 of them were estimated have dual nationality, accounting for 74% of the total. If not properly handled, the issue of their nationality would have an adverse impact on relations between the two countries as well as the life of overseas Chinese in their residing country.

When meeting the Burmese Ambassador on August 1, 1950, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai asked about the relationship between the intermarriage of local overseas Chinese and Burmese and the nationality of those married overseas Chinese. 10 Burmese Prime Minister U Nu paid his first visit to China in December 1954. After the meeting, the two sides agreed that “regarding the nationality of the overseas Chinese in Burma, the two governments will have consultations through diplomatic channels at an early date.” 11 On October 13, 1955, U Hla Maung, Burmese Ambassador to China, inquired whether China would approve the renunciation of Chinese nationality by overseas Chinese who had attained Burmese nationality. Burma was ready to negotiate with China on the issue of dual nationalities. 12 Soon afterwards, after some study and discussion, China drafted a joint communiqué and was ready to accept Burma’s request. 13 However, China later changed its stance, believing that the Burmese government was intending to “reach a partial agreement first, the basis of which would give the Burmese side some edge in deciding whether the negotiation for an once-and-for-all solution to the question of nationality of overseas Chinese should start, or to drag it out, whichever played in their advantage.” 14 Therefore, China did not respond to Burma’s request and had no negotiations with it. In spite of this, China showed a positive attitude towards overseas Chinese attaining Burmese nationality, believing that “as the acquisition of Burmese nationality by overseas Chinese in Burma is beneficial to our country both politically and economically, a policy should be adopted to encourage a large number of overseas Chinese to acquire the Burmese nationality.” 15 And: “It is more than beneficial to us if local overseas Chinese have obtained Burmese nationality.” 16

When meeting with the Burmese Ambassador on June 22, 1956, Premier Zhou said, “The basic principle for China is that we are in favor of more overseas Chinese, who were born in their residing countries and are willing to stay there, acquiring the nationality of those countries.” 17 That meant China accepted Burma’s granting of its nationality to local overseas Chinese. At the welcoming gathering hosted by local overseas Chinese on December 18, 1956, Zhou Enlai made it very clear to the overseas Chinese and the Burmese side that it was gratifying that “some overseas Chinese who have stayed for long in Burma, have become Burmese citizens by having acquired Burmese nationality…. As long as they have made the choice on a voluntary basis, and as permitted by the local laws, obtained the nationality of their residing country, they are no longer regarded as Chinese citizens.” 18

Although China and Burma did not reach an agreement on the dual nationalities of overseas Chinese, Premier Zhou Enlai’s remarks in Rangoon in 1956 clearly indicated that China not only respected and understood the fact that the overseas Chinese had been in Burma for a very long period of time, but also encouraged those who had lived long enough in Burma to become Burmese citizens and opposed dual nationalities. In the early 1950s, there were some 140,000 Burmese of Chinese and Burmese parentage, the native-born descendants of the old generations of overseas Chinese totalling about 80,000. Burma naturally granted these 220,000 residents Burmese citizenship. China also supported and agreed to their becoming Burmese citizens. This group of people also identified themselves with the local communities. U Min Thein, former Burmese Ambassador to China, once remarked that “it seems that these people regard themselves as Burmese. When the Burmese government had all foreign nationals registered, they didn’t show up for it. It is true that they don’t use their Chinese names in Burma…. In Burma there are many people of Guangdong and Fujian origin. The Burmese regard them as Burmese, while the Chinese consider them to be Chinese. In fact, their wives and mothers are Burmese.” 19 Therefore, although there were about 260,000 overseas Chinese who had been assumed to have dual nationalities after Burma’s independence, 85% of them had their nationality problem settled due to China and Burma’s agreement on the nationality of overseas Chinese of Chinese and Burmese parentage and native-born descendants of old generations of overseas Chinese, as well as these people’s own self-identification.

It was significant for the two countries to reach a consensus on the nationality of overseas Chinese. It was, however, far more important to solve the issues of political identification and economic role of the overseas Chinese with the changed nationality so that the Burmese government’s suspicion of the overseas Chinese as a pawn of red China could be dispelled.

The Political Issue of Overseas Chinese

During the Cold War, overseas Chinese in Southeast Asian countries were seen as a “fifth column” in their residing countries to be used by China for the purpose of infiltration and expansion. More often, overseas Chinese were the target of nationalism and ideology. The Burmese government was very much concerned about the involvement of overseas Chinese in its politics, for fear that the Chinese government might take advantage of them to interfere in Burma’s internal affairs.

When meeting with Premier Zhou Enlai, U Ba Swe, Ambassador to China, raised the issue of overseas Chinese in Burma sponsoring the election campaigns of candidates from the National Front: “They do business with Burmese partners and spend some of their earnings sponsoring the election. While campaigning for the election, the ‘National Front’ candidates can get financial assistance from local overseas Chinese with a letter of reference.” Zhou Enlai responded, “China’s position is that if the overseas Chinese do not have the citizenship of their residing countries, they are not entitled to participate in local political activities…. We keep to this. If the overseas Chinese who are not Burmese citizens are involved in what you said, we will support the Burmese government in stopping them from doing so. That is to say, we hold the same position as the Burmese government. It is wrong for the Burmese government to assume that we side with the overseas Chinese in Burma. As for the business cooperation between overseas Chinese and Burmese and the way their money is spent, the Burmese government has the right to make an investigation into it.” Later, after exchange of views and with the effort of the Chinese side, U Nu “on several occasions denounced the accusation against China as groundless.” The issue from then on was not brought up again. 20

Former Prime Minister U Ba Swe told Zhou Enlai in 1960 that “during the 1960 general election campaign, the leftist overseas Chinese financially supported the ‘Clean’ faction of the AFPFL, enabling them to spend money like dirt. We hope your Excellency could do something to stop this. The leaders of the ‘Clean’ faction of the AFPFL across Burma asked for financial support from the overseas Chinese businessmen in their own names and the businessmen did not hesitate to give it to them.” Zhou Enlai answered, “The Chinese government has an explicit policy that overseas Chinese who haven’t obtained Burmese nationality are not allowed to take part in Burmese political activities. I have told them several times. Our embassy also educates the local overseas Chinese based on this policy.” The Chinese Ambassador to Burma also said, “Before the election, our Embassy specially summoned overseas Chinese who have not acquired Burmese nationality, telling them not to participate in Burmese political activities. 21 In response to Burma’s accusation that the Rangoon Branch of Bank of China was involved in supporting U Nu, Zhou Enlai said that the Burmese government had the right to check the accounts of the branch in Rangoon, and “we are opposed to the practice of some parties who demanded donations from businessmen. But some businessmen may contribute money under the influence of others”. 22

In fact, when China and Burma began high-level mutual visits in 1954, China made clear its position on and attitude to the political issues of overseas Chinese in a clearcut manner. During Burmese Prime Minister U Nu’s first visit to China, Mao Zedong told him, “We will not set up communist organizations among overseas Chinese in Burma. All branches that were there have dissolved. We have done exactly the same in Indonesia and Singapore. We told the overseas Chinese not to take part in political activities in Burma. They are only allowed to participate in what the Burmese government permits, for example, celebrations. Otherwise, they would be put in a very embarrassing and difficult situation…. There are extremists among overseas Chinese. We persuade them not to meddle in Burma’s internal affairs. We tell them to abide by the law of their residing country and not to get in touch with any party that goes against the Burmese government through armed struggle.” 23

At the welcoming gathering hosted by overseas Chinese in Rangoon on December 18, 1956, Zhou Enlai stated China’s attitude in a more systematic manner: an overseas Chinese “should do what he is supposed to do, try to be a good resident, a law-abiding resident, and above all a model resident.” He said that who have obtained Burmese citizenship should distinguish themselves from those haven’t. The former should not join any overseas Chinese organizations and the latter should not participate in Burmese political activities. “Overseas Chinese are not allowed to join any Burmese parties, take part in elections or any other political activities. They should stay away from these…. In addition, we will not develop the organizations of the communist party or other Chinese democratic parties. We must draw a clear line here. Some may join the parties after returning to China, but are never allowed to do so here in Burma. 24 During this visit, Zhou Enlai stated explicitly that, “politically, we hold that those who have attained suffrage in Burma should be regarded as Burmese citizens and will no longer have Chinese nationality, and are therefore not allowed to join overseas Chinese organizations and activities. Similarly, if some overseas Chinese still maintain their Chinese nationality, they should keep themselves away from any Burmese political activities. 25 The author has been told by a senior overseas Chinese in Rangoon that, in addition to expressing his attitude and giving instructions, Premier Zhou said “on almost every public occasion that overseas Chinese should not get involved in local political activities” during every one of his nine visits to Burma.

Although the 1950s saw some twists and turns in the political issue of overseas Chinese, generally speaking, the Chinese government’s attitude and commitments and the fact that overseas Chinese stayed away from local politics, assuaged Burma’s deep concern.

The Economic Role of Overseas Chinese

The economic strength and importance of overseas Chinese was another reason for the emerging nationalist countries to be suspicious and to pay vigilant attention. For a long time, local political elites, nationalist extremists, and some interest groups had stirred up anti-Chinese campaigns, accusing overseas Chinese of “controlling the economic lifelines of Southeast Asian countries.” Economic nationalism was one of the core aspects of postwar nationalist movements in Southeast Asia. After winning political independence from 1945, Southeast Asian countries adopted measures to seek economic independence. Before Burma’s independence, its economy was controlled by British colonialists, Indians, and overseas Chinese. After independence in 1948, economic Burmanization became a key policy. 26 In the 1950s, Burmese economic nationalism mainly targeted land, banking, mining, and commerce. Because the overseas Chinese community was commerce-oriented and mostly engaged in trade and retail businesses, it was greatly affected by the economic nationalization policy, which “gave priority to Burmese in terms of commerce and trade.”

China believed these changes in Southeast Asia boiled down to “the conflict between the commercial economy of overseas Chinese and the local national economy.” The rapid development of Southeast Asian national economies required a start-up in the sector of commerce. In this sense, the commercial business of overseas Chinese would naturally become a target for containment. Local governments resorted to legal means by adopting national assimilation policies in all industries to control their economies. “We suggest part of the capital of overseas Chinese be transferred to industry so that we can gain a better position in taking the initiative politically and finding a solution to the conflicts between overseas Chinese and the people of their residing country, and between the economy of overseas Chinese and the local economy.” 27 While taking a limited number of economic Burmanization measures which mainly focused on commerce and the import and export trade, the Burmese government encouraged overseas Chinese to invest in Burmese industry. During Premier Zhou Enlai’s visit to Burma in 1956, Prime Minister U Ba Swe told Zhou that “since Burma has nationalized the pawn trade, there might be some idle funds in the hands of overseas Chinese. If this money is invested in the development of industry, the Burmese government, instead of opposing to it, will help with the capital transfer.” 28

During his 1956 visit, Zhou Enlai told the overseas Chinese that if they want to be settled in Burma, they’d better have a long-term plan. Engaging in commerce may sometimes be risky, while investing in industry was a good prospect: “The investment returns from industry are slow but steady. Entrepreneurs of vision should engage in this field, putting their idle funds into Burma and cooperation with the Burmese. Developing industry and handicraft industry with the approval of the Burmese government is a far-sighted long-term plan. By doing so, we can make our share of contribution to Burma’s development.” 29

The Chinese government not only gave policy incentives to overseas Chinese to transfer from commerce to industry, but also provided substantial support in technology and equipment. For example, when Burmese overseas Chinese intended to establish a joint paper mill in the mid and late 1950s, the Chinese Foreign Ministry, Ministry of Foreign Trade, and Ministry of Light Industry, after careful study, suggested that in terms of profit sharing, settlement of foreign exchange earnings, duration of operation before being nationalized, refund of equity capital, and management training, the overseas Chinese investors “should not demand too much, for fear that these may lend more suspicion to the Burmese government. Our readiness to provide assistance and support to the Burmese side in machinery and technology demonstrated the willingness of the Chinese government to guide and support overseas Chinese in their transfer from commerce to industry.” 30 The Chinese Embassy also said that “the industry owned and operated by overseas Chinese has a short history and a weak foundation, but as an emerging force, it moves hand in hand with efforts to integrate Burma’s whole economy. This is the only way out. It conforms not only to the needs and interests of the Burmese economy, but also to the long term interests of overseas Chinese. The economy of overseas Chinese must be oriented towards the local community and local people and integrated into the Burmese national economy, contributing to Burma’s economic prosperity and playing a positive role in improving the living standard of Burmese people”. 31

Meanwhile, a small number of overseas Chinese businessmen’s unscrupulous way of making profits enraged local governments and peoples. Burmese Prime Minister U Ba Swe told visiting Premier Zhou Enlai, ”The majority of overseas Chinese are good. But some overseas Chinese businessmen speculate in the black market and have a negative impact on the market. The Burmese government hopes that overseas Chinese could transfer their capital into developing industry.” 32 In response, Zhou Enlai instructed that “overseas Chinese, either engaged in business or industry, should abide by the Burmese law and refrain from doing what is illegal and immoral.” They should not drive prices unjustifiably high or engage in black market business which undermines the interests of the general public. “Rather, they should be model businessmen of high morality and integrity.” 33

The economic issue of the overseas Chinese was not as prominent as the political issue due to the correct guidance of the two governments and the shift of overseas Chinese from business to industry. Another important reason was that the economic strength of overseas Chinese in Burma was far weaker than that of overseas Indians, which drew more attention.

The Relationship Between Ethnic Groups

Friendly and harmonious relations with local people constitute an important prerequisite for the life of overseas Chinese in local communities, easing the tension resulting from nationalism, protecting their own interests, and facilitating communication between their residing country and their mother country.

To get on well with local people and become integrated into the mainstream of society, it is necessary for overseas Chinese, as immigrants, to have a positive, reasonable, and cooperative mentality. Premier Zhou Enlai once told overseas Chinese to stay away from chauvinism and egotism. “Instead, prefer an attitude of modesty and prudence, which is essential for fostering a sound relationship whether between people or between nations.” 34 Commenting on the remarks of Zhou Enlai, Mr. Li Jun, former chief editor of Rangoon People’s Daily, said, “I was present when Zhou Enlai made these remarks, which exerted a huge impact later on. And it was from then that the overseas Chinese began discarding their Han chauvinism” 35

Burma is a country of Buddhism, with its followers accounting for the majority of its population. Buddhism represents the foundation and core of Burmese culture. Customs and habits, as part of culture, are formed in the long course of historic development in such fields as diet, clothing, housing, marriage, funeral, festive celebrations, and entertainment. Customs and habits are a reflection of each ethnic group’s historic traditions, psychology, religious beliefs and so on, thus constituting an important aspect of each ethnic group’s traits. Therefore, respecting and accepting local people’s religious beliefs and customs determines, to some extent, the closeness and integration with local mainstream culture and the acceptance and recognition of overseas Chinese by the Burmese people. To this end, Chinese leaders instructed that “overseas Chinese should respect the residing country’s customs and religious beliefs. We hold that overseas Chinese should build up friendships and even kinship with local people, which are instrumental to securing a peaceful permanent settlement of overseas Chinese in the residing country.” 36

Zhou Enlai encouraged intermarriage between overseas Chinese and Burmese. He believed that “intermarriage is helpful. When meeting Burmese friends, we are very proud that many of them have a blood bond with Chinese and that we have so many kin and relatives in this country….. It is worth celebrating that overseas Chinese marry Burmese. Some of you or your relatives have married our Burmese friends, to whom I send my best wishes.” 37 As for the purpose of encouraging intermarriage between overseas Chinese and local people, Zhou Enlai stated it explicitly as early as August 1951, at the 99th meeting of the Chinese State Council: “There are over 10 million overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia. We should encourage them to intermarry with local people rather than restrict it. Only by doing so can they be assimilated into the locals and move forward with them.” 38

As language is both a symbol of culture and a tool of communication, a mastery of local language is one of the preconditions for overseas Chinese, as immigrants, to be assimilated into local society and to build a good relationship with the local community. Zhou Enlai instructed that overseas Chinese in Burma should have a good command of Burmese so that they can communicate with Burmese people freely and directly. “It is a shame for you not to learn a foreign language well. Some people, who have stayed abroad for decades, still do not understand a single sentence of the local language…. I suggest that overseas Chinese learn the foreign language well. And still more should the young generation of overseas Chinese in Burma understand Burmese…. It is good for overseas Chinese newspaper to have pages in Burmese added. Overseas Chinese should read both Chinese and Burmese. At overseas Chinese school, Burmese must be a compulsory course.” 39 Guided and supported by the Chinese government, Burmese overseas Chinese “began to enhance Burmese teaching and learning starting in the mid 1950s. And it proved helpful after years of effort.” 40 In September 1957, the Burmese Overseas Chinese Teachers’ Association, the top regulator of Chinese Education in Burma, adopted a resolution requiring all Chinese schools to intensify Burmese teaching and incorporate Burmese courses into the curriculum. Some Chinese school even implemented a policy of “one school, two curricula (Chinese and Burmese).”

Conclusion

Victor Purcell, the renowned historian of Southeast Asian studies, asserted that after WW II, the withdrawal of colonialists and the start of communist party rule in China signified that the two forces overseas Chinese used to depend upon changed at the same time. 41 The change in the destiny of overseas Chinese brought about by the change in the times is mainly reflected in the issues of legal identity, political recognition, economic role, and relationship with the local people. Although overseas Chinese in emerging Southeast Asian nationalist countries were faced with the same challenges, their situation varied from country to country due to differences in the size of the local overseas Chinese population, their economic strength, their level of assimilation, and the relations between China and their residing countries. Compared with overseas Chinese in other Southeast Asian countries, the overseas Chinese community in Burma was smaller, economically weaker, more assimilated into the local community, and had a better relationship with the locals. This accounts for the fact that the issue of overseas Chinese did not become prominent in Sino-Burmese relations. A more important reason, however, is the policies the two countries adopted towards each other.

In the 1950s, Burma, located at the convergence of South and Southeast Asia, expressed on several occasions its worry that the New China might undermine its national security and the necessity and importance of maintaining friendly relations with China and other big countries: “The Burmese government was fully aware that geopolitics is something that can not be changed…. Burma’s policy of neutrality is a policy choice based on its fundamental national interest. In other words, the national interest dictates non-confrontation with Communist China.” China considered Burma as a breaking point to counter western strategic encirclement and blockade. Reviewing the overseas Chinese question in Burma against such a backdrop, one can clearly see that the solution conforms to the national interests of both countries, which is the top priority in bilateral relations. The Burmese government would not offend China for this reason. 42 China pursued a policy of safeguarding the rights and interests of overseas Chinese and and the overall interests of Sino-Burmese relations, but when the two collided, the former had to give way to the latter. Consequently, for the overseas Chinese, the Burmese government adopted a policy combining restriction with utilization. The overseas Chinese faced pressure from Burmese nationalism while still enjoying some degree of living space. China’s policy on nationality, politics, economy, and the relationship of overseas Chinese with other ethnic groups always served the purpose of assisting their peaceful permanent settlement and dispelling the suspicion that overseas Chinese were a “fifth column.” In so doing, China assured that the issue of overseas Chinese would not pose an obstacle to bilateral relations.

Fan Hongwei

Lecturer, Centre for Southeast Asian Studies, Xiamen University

This article was first published in Southeast Asian Affairs 2007, no. 1, and was translated for KRSEA by Ding Hao.

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia Issue 10 (August 2008): Southeast Asian Studies in China

Notes:

- “Summary on the National Day Celebrations at Embassy in Burma,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No.117-00038-02(1). ↩

- “Premier Zhou Enlai Holds Banquet in Honor of Prime Minister U Nu,” Xinhua Biweekly, 1957 (9). ↩

- “Burmese Government Officials and the Media’s Response to Premier Zhou Enlai’s Visit to Burma,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No.105-00259-03. ↩

- “Account of Chairman Mao Zedong’s Talk with Visiting Burmese Deputy Prime Ministers, U Ba Swe and U Kyaw Nyein,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 105-00339-01(1). ↩

- “Situations in Burma,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 102-00055-04(1). ↩

- “Burmese Foreign Minister’s Opinion on Chinese Ambassador’s Remarks at Local Overseas Chinese Gathering and China’s Response to It,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 105-00067-02(1). ↩

- “First Secretary Denies the Establishment of Military Bases by the US in Burma,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 105-00174-02(1). ↩

- “Burmese Embassy in China Demands Chinese Foreign Ministry to Publish an Explanation Article on Yunnan Daily to Clarify the Incorrect Message in Thakin Lwin’s Essay,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 105-00078-01(1). ↩

- G. William Skinner, “Overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 321 (January 1959). ↩

- “Brief Account of the Talk between Premier Zhou Enlai and Burmese Ambassador U Min Thein,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 105-00002-01(1). ↩

- “Talk Between the Chinese Premier and the Burmese Prime Minister,” People’s Daily, December 13, 1954. ↩

- “Brief Account of the Talk between Foreign Minister Zhang Hanfu and U Hla Maung, Burmese Ambassador to China (at half past ten, October 13, 1955),” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 105-00175-03(1). ↩

- “Advice on the Nationality of Burmese Overseas Chinese,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 105-00510-03(1). ↩

- “Files on the Dual Nationalities of Burmese Overseas Chinese Compiled by the Department of Asian Affairs of Ministry of Foreign Affairs,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 105-00510-10(1). ↩

- “Files on the Dual Nationalities of Burmese Overseas Chinese.” ↩

- “Advice on the Nationality of Burmese Overseas Chinese.” ↩

- “Account of the Talk between Premier Zhou Enlai and Burmese Ambassador to China, U Hla Maung (on August 25, 1956),” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China,No. 105-00307-02(1). ↩

- “Remarks by Premier Zhou Enlai at the Welcoming Gathering of Overseas Chinese in Rangoon, Burma,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 105-00510-08(1). ↩

- “Account of the Talk between Foreign Minister Zhang Hanfu and U Min Thein, Burmese Ambassador to China,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 105-00002-02(1). ↩

- “Brief Account of the Talks between Premier Zhou Enlai and Burmese Leaders,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 203-00019-02(1). ↩

- “An Account of the Talk between Premier Zhou Enlai and Former Burmese Prime Minister, U Ba Swe,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 203-00036-04(1). ↩

- “A Brief Account of Premier Zhou Enlai’s Visit to Burma,” Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 203-Y0036. ↩

- Works of Mao Zedong, vol. 6 (Beijing: People’s Press, 1999), pp. 376-77. ↩

- “Remarks by Premier Zhou Enlai at the Welcoming Gathering of Overseas Chinese in Rangoon, Burma.” ↩

- Chronicle of Zhou Enlai 1949-1976, vol. 1 (Beijing: Central Compilation Press, 1997), p. 647. ↩

- Frank H. Golay, Underdevelopment and Economic Nationalism in Southeast Asia (Ithaca, NY and London: Cornell University Press, 1969), pp. 211-262. ↩

- “On Overseas Chinese Affairs,” Archives of Office of Overseas Chinese Affairs, The State Council, 1992. ↩

- “Brief Account of the Talks between Premier Zhou Enlai and Burmese Leaders.” ↩

- “Remarks by Premier Zhou Enlai at the Welcoming Gathering of Overseas Chinese in Rangoon, Burma.” ↩

- “On the Joint Paper Mill between Burmese Overseas Chinese and the Burmese Government,”Archive of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, No. 105-00339-07(1). ↩

- “Survey on Overseas Chinese Economy in Rangoon by Chinese Embassy in Burma,” October 15, 1958 (publisher unknown). ↩

- “Brief Account of the Talks between Premier Zhou Enlai and Burmese Leaders.” ↩

- “Remarks by Premier Zhou Enlai at the Welcoming Gathering of Overseas Chinese in Rangoon, Burma.” ↩

- “Remarks by Premier Zhou Enlai at the Welcoming Gathering of Overseas Chinese in Rangoon, Burma.” ↩

- Author’s interview with Li Jun, Burmese Overseas Chinese Returnee, Kunming, China, December 6, 2003. ↩

- “Remarks by Premier Zhou Enlai at the Welcoming Gathering of Overseas Chinese in Rangoon, Burma.” ↩

- “Remarks by Premier Zhou Enlai at the Welcoming Gathering of Overseas Chinese in Rangoon, Burma.” ↩

- Chronicle of Zhou Enlai 1949-1976, vol. 1 (Beijing: Central Compilation Press, 1997), p. 647. ↩

- “Remarks by Premier Zhou Enlai at the Welcoming Gathering of Overseas Chinese in Rangoon, Burma.” ↩

- Author’s interview with Feng Lidong, Burmese Overseas Chinese Returnee, Xiamen, China, April 23, 2003. ↩

- Victor Purcell, “Chinese Society in Southeast Asia,” in Southeast Asia: The Politics of National Integration, ed. John T. McAlister, Jr. (New York: Random House, 1973). ↩

- The June 26th Incident in 1967 was an exception in that special period of time. For related research into it, please refer to “The June 26th Incident in 1967 and Studies of Burmese Society,”Taiwan Southeast Asian Studies Journal, vol. 3 (2006): 47-72. ↩