Amir Muhammad

“Perforated Sheets,” a newspaper column

Kuala Lumpur / New Straits Times / 2 September 1998 – 3 February 1999

Sabri Zain

Face Off: A Malaysian Reformasi Diary (1998–99)

Singapore / Options Publications / 2000

Shahnon Ahmad

SHIT@Pukimak@PM (Novel Politik Yang Busuk Lagi Membusukkan)

(SHIT@Pukimak@PM: A political novel that stinks and creates stinks)

Kubang Krian, Kelantan, Malaysia / Pustaka Reka / 1999

Dr. Mahathir Mohamad, now approaching his twenty-first year in office as Malaysia’s fourth premier, has long treated politics as mostly a matter of economics, and supposedly hard-nosed economics, to correct “Malay relative backwardness” and to make Malaysia a “developed country.” For him, culture held little attraction, especially the culture of his majority ethnic Malay community which he regarded as being deficient and in need of rectification. In 1998-99, Mahathir’s regime was rocked by a Malay cultural revolt that arose after Mahathir dismissed his deputy, Anwar Ibrahim, on 2 September 1998.

Several events deepened the revolt against Mahathir’s regime. Less than forty-eight hours after his dismissal, Anwar, whom UMNO had elected deputy president in 1993 and 1996, was expelled by the ruling party’s Supreme Council. The state-controlled mass media sensationalized the “reasons” for Anwar’s fall—chiefly allegations that Anwar had committed adultery with his secretary’s wife (and other unnamed women) and sodomy with his driver, his speech writer, and his adopted brother. Perhaps Mahathir and his allies expected that the tawdry allegations of sodomy (a crime under Malaysian law and a sin against Islam), would stun Malaysian society, especially the Malay/Muslim community, into a cowed acceptance of Anwar’s guilt. If so, they miscalculated. Mahathir, who had little empathy for Malay culture, had transgressed against a “social contract” going back to the Malay Annals that forbade a ruler from shaming the ruled (Cheah 1998).

Refusing to fade away, however, Anwar called for Reformasi—for reforms that opposed Mahathir’s “cronyistic” responses to the 1997 East Asian financial crisis and that carried, in the Malay language, echoes from the Indonesian movement against kolusi, korupsi, nepotisme (collusion, corruption, and nepotism) that had toppled Suharto’s New Order regime in May 1998. On 20 September 1998, balaclava-clad, submachine-gun-toting commandos broke into Anwar’s home, arrested Anwar, and whisked him to the national police headquarters in Bukit Aman, Kuala Lumpur. There, a handcuffed and blindfolded Anwar was severely beaten by the Inspector-General of Police. Days later, an injured and black-eyed Anwar was officially charged with ten offenses in the first of two trials, which began in November 1998.

Refusing to fade away, however, Anwar called for Reformasi—for reforms that opposed Mahathir’s “cronyistic” responses to the 1997 East Asian financial crisis and that carried, in the Malay language, echoes from the Indonesian movement against kolusi, korupsi, nepotisme (collusion, corruption, and nepotism) that had toppled Suharto’s New Order regime in May 1998. On 20 September 1998, balaclava-clad, submachine-gun-toting commandos broke into Anwar’s home, arrested Anwar, and whisked him to the national police headquarters in Bukit Aman, Kuala Lumpur. There, a handcuffed and blindfolded Anwar was severely beaten by the Inspector-General of Police. Days later, an injured and black-eyed Anwar was officially charged with ten offenses in the first of two trials, which began in November 1998.

This constellation of events, briefly noted here, provoked huge, mostly spontaneous protests against Mahathir’s regime. In towns and villages, within the civil service, on university campuses, among students studying overseas, and even at UMNO’s lower levels, Malay popular opinion expressed moral revulsion at Anwar’s shaming, his family’s humiliation, and the community’s disgrace. The revulsion deepened with the media’s lurid descriptions of Anwar’s alleged homosexual acts, the secret assault on him which Mahathir initially dismissed as being possibly “self-inflicted,” and the prosecution’s almost lewd conduct of parts of the trial. Moral outrage turned into political opposition as peaceful protesters were incessantly attacked by riot police in the streets, near mosques, and close to the courthouse where Anwar was being tried.

That turmoil produced political outcomes which cannot be covered by this essay. But Reformasi blossomed as a cultural movement producing writings and art forms that variously criticized, challenged, and mocked Mahathir and his regime. Reformasi came to stand for alternative media of expression, communication, and debate which were unshackled by state censorship, if not quite liberated from state retribution. A notable example was the five-fold increase in circulation of Harakah, the twice-weekly organ of Parti Islam (PAS) (to 300,000 copies from 65,000 before Reformasi), despite legal restrictions on the sale of party newspapers to non-party members. New Malay-language magazines such as Tamadun, Detik, Wasilah, and Eksklusif flourished with a steady stream of criticism. Internet Reformasi websites mushroomed. Some belonged to opposition parties and non-governmental organizations. Some sites, like Raja Petra Kamaruddin’s The Malaysian and Kini, were kept by individuals who disdained to conceal their names or goals. Many more sites were anonymously maintained but made clear their principal concerns by their designations and “links”: Laman Reformasi (Reformasi Website), Jiwa Merdeka (Soul of Independence), Anwar Online, freemalaysia, et cetera. Yet others flaunted names like Mahafiraun 2020 (Great Pharoah 2020) or Mahazalim (Great Tyrant) in derision of Mahathir.

It would, of course, take more than a short essay to adequately interpret the immense literary output of Reformasi. This essay has the limited aim of taking some sounding of Reformasi’s underlying social and political themes by offering a political reading of a set of newspaper articles, a diary, and a novel. These were written by Malay authors critical of the regime and/or sympathetic to Anwar to different degrees. All the writings were quite popular among dissident circles.

Amir Muhammad: The arms of criticism

On 2 September 1998, the Literary & Books section of the English-language broadsheet New Straits Times carried an article, “The importance of being ‘queer’,” in the fortnightly column “Perforated Sheets.” Amir Muhammad, the columnist, would no doubt have found it uncanny that his article, bearing such a headline and speculating on links between literary talent and homosexuality, should have appeared the very day the Anwar affair began.

Yet the article (which had no reference to any local person) could scarcely have had Anwar in mind, let alone have divined his fate. Amir was then, as he is now, neither a prude nor a hack but a brilliant, young, independent literary and film critic who kept his column bristling with entertaining erudition and irreverent wit. And although he was capable of clever political asides, overt politics was not the main fare of “Perforated Sheets.” That changed with Amir’s first piece published after the Anwar affair began and continued until his last article appeared on 3 February 1999. During this period, as Kuala Lumpur seethed with Reformasi fervor, Amir employed bitingly sarcastic literary criticism to make connections, or urge his readers to make their own connections, between art and life. In “We don’t need monodramas” (16 September 1998), he derided the regime’s blatantly partisan coverage of the Anwar affair as a “style of theater” mounted by “an uncharismatic monodramatist who insists on shoving all his views down my throat,” leaving him feeling “dirty, ravaged and violated.” Two weeks later came “The beginning of The Trial” (30 September 1998), which invited readers to ponder Joseph K’s fate in Kafka’s classic “allegory of totalitarian state control” and to thereby raise questions about Anwar’s impending prosecution. “Megalomaniacs don’t last” (14 October 1998) introduced Mark Leyner’s novel, Et Tu Babe, that showed the “strange and horrible things that happen when the idea of dictatorship is taken to its logical conclusion.” Two further articles (“Deny thy country, young man,” 28 October 1998, and “Our patriotism running amok,” 9 December 1998) ridiculed the regime’s claim to all manner of patriotism, which it used to deflect local and international criticism. In the latter article, Amir flayed a bureaucratic “literary nationalism” that nominated Malaysian (Malay) literature for the Nobel Prize and “the Pulitzer and Booker prizes … [forgetting] that the former is open only to American books while the latter only picks stuff published in Britain and written in the English language.” “Justice in The Crucible” (11 November 1998) drew parallels between Arthur Miller’s play about witch-hunts in seventeenth-century Salem, Massachussetts, and Anwar’s ordeal to stress that a “pernicious cycle of cold lies and hot resentment” allowed “some people [to] seize [a] trial as a chance to settle old scores or pursue their own hidden agenda.” Such a reading of The Crucible intimated associations between Umi Hafilda, one of the prosecution’s “star witnesses,” and “the scheming Abigail,” and between Dr. Wan Azizah, Anwar’s wife, and “the virtuous Elizabeth.”

Amir let fly his maverick imagination with his first piece for 1999: “20 books that we need” (6 January 1999). The truly funny “20 book ideas that I hope to see fully fleshed out… by the millenium’s end” covered the “talking points” of the Anwar trial. Notable examples (and their subjects in real life) included: “Clothes coordination for siblings” (Umi Hafilda and her brother’s wardrobe during Umi’s court appearances); “Out, out, damn spot!” (a semen-stained mattress brought to court by the prosecution); “The allure of the black eye” (Anwar’s bashed-up face); “An intelligent parent’s guide to sodomy and other painful issues” (testimony by Anwar’s ex-driver on Anwar’s alleged sodomy); “Excuse me, are you an SB officer?” (the role of the Special Branch police); and “Tips for terrific turn-overs” (Special Branch interrogation techniques).

Amir’s concluding lines deserve separate mention. The Kafka review exhorted: “For more answers, don’t look at me. Get up and march—to a bookstore.” The piece on “megalomaniacs” concluded: “But, hey, when he’s got to go, he’s got to go!” The article on The Crucible remarked that “Our real pity and loathing is reserved for the citizens who did not take a stand when their neighbors were victimised. By the time they realised that they were next on the list, it was already too late, since the forces of unreason had been permitted to hold dominion for so long.” And at the end of “The comedy of American Psycho” (20 January 1999): “… at the very least, you realize that the task of parodying a society that’s rapidly turning into a parody of itself can be murder.”

To poke fun at a regime in trouble is to perforate its legitimacy, which was a large part of what Reformasi meant. It was presumably why Amir’s popular column was wrapped up. But note Amir’s preference for “unreason” over, say, “repression,” which most dissidents would have seized upon, and his choice of “parody,” which few others would have used to depict the tumultous transformation of society. Amir’s irony ill-concealed his disapprobation but his prose remained polished, arguably polite. No doubt Amir had an attitude, but it was generally anti-establishment rather than deliberately anti-regime at the 1998-99 conjuncture. In that Amir perhaps wrote as if Reformasi was staring at him from the streets of Kuala Lumpur.

Sabri Zain: A shopper’s diary

I admire Amir’s work and mean him no slight by saying that Sabri Zain, on the other hand, wrote from the streets. To be precise, Sabri (usually with his “significant other”) moved between the street and the Net, between participating in “Reformasi events” and dashing home to spread the “alternative” news via his online Reformasi Diary. Sabri kept his diary and shared his insights at a time when no one in his right political mind believed the mainstream media.

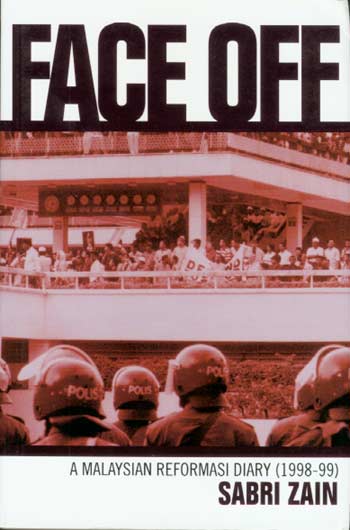

Face Off is the print version of Sabri’s original (and longer) diary. The book contains forty “entries” covering the year between 20 September 1998 and 19 September 1999, as well as an introduction and epilogue. Here, in the jottings of an “Internet journalist,” one encounters the very stuff of politics as drama—protests in the streets, rallies in Merdeka Square, escapes from police attack, candlelight vigils outside prisons, trekking in mud to ceramah (political talks) under dark, queuing to enter the courthouse, and the launching of the National Justice Party (led by Wan Azizah) in a hotel. From Sabri’s “participant observation” the reader gets a dissection of the dynamic of “face off” between ordinary, unarmed, peaceful protesters and baton-wielding “Red Helmets” (Federal Reserve Unit riot police) and plainclothes Special Branch personnel backed by water cannon. Here, with sincere and light-hearted humility, is a moving tribute to the nameless heroes and heroines Sabri met—“elderly men, middle-aged men and women, young girls… senior managers in the private sector… executives or civil servants, teachers, businessmen, laywers,” and “Rockers in leather jackets.” In their ranks were hundreds of Orang Kena Tuduh (legalese for “the accused”), people who had been detained by the police for “illegal assembly.” To them Sabri’s book is dedicated. Their varied backgrounds reveal Reformasi’s broad social front along which the regime’s legitimacy was lost.

Face Off is the print version of Sabri’s original (and longer) diary. The book contains forty “entries” covering the year between 20 September 1998 and 19 September 1999, as well as an introduction and epilogue. Here, in the jottings of an “Internet journalist,” one encounters the very stuff of politics as drama—protests in the streets, rallies in Merdeka Square, escapes from police attack, candlelight vigils outside prisons, trekking in mud to ceramah (political talks) under dark, queuing to enter the courthouse, and the launching of the National Justice Party (led by Wan Azizah) in a hotel. From Sabri’s “participant observation” the reader gets a dissection of the dynamic of “face off” between ordinary, unarmed, peaceful protesters and baton-wielding “Red Helmets” (Federal Reserve Unit riot police) and plainclothes Special Branch personnel backed by water cannon. Here, with sincere and light-hearted humility, is a moving tribute to the nameless heroes and heroines Sabri met—“elderly men, middle-aged men and women, young girls… senior managers in the private sector… executives or civil servants, teachers, businessmen, laywers,” and “Rockers in leather jackets.” In their ranks were hundreds of Orang Kena Tuduh (legalese for “the accused”), people who had been detained by the police for “illegal assembly.” To them Sabri’s book is dedicated. Their varied backgrounds reveal Reformasi’s broad social front along which the regime’s legitimacy was lost.

Sabri’s accounts of landmark Reformasi events are unsurpassed for their accuracy, balance, and spirit. His choice of simple words often befits the occasion admirably. For example, when “not wishing to break the law Reform movement organizers ‘invited’ Malaysians to join them ‘shopping’ in downtown Kuala Lumpur”; Sabri accepted the invitation and afterwards wrote “Shopping For Justice.” The title phrase at once captured the spontaneous, fluid, and inchoate character of early Reformasi protests. Queuing in a forlorn attempt to get a seat in the packed courtroom of Anwar’s trial inspired “Waiting For Justice,” while “An Evening With Justice” recorded the equally packed Breaking of Ramadan Fast with Wan Azizah at the Renaissance Hotel on 16 January 1999. And, finally, “The Eye Of Justice” summed up several motifs in the founding of the National Justice Party: its logo was an eye formed of two blue crescents, its cause célèbre had suffered a black eye, and its first president was an opthamologist!

Any good diary must capture changing moods, colors, and sentiments. Face Off does exactly that. It not only records the fears, pains, and anger felt at street level. It also catches the broader cynicism via spoofs which Sabri created in the mold of lengthy internet jokes: “Malaysia’s top brains answer the call for a PM ‘replica’,” “A brief (but helpful) guide to reading the Malaysian press,” “Protecting your child from politically-explicit online material,” and “The Reformasi aptitude test.” Above all, Sabri himself registers surprise at the rapid change in social and political attitudes. Almost unimaginable before Anwar’s fall and Reformasi’s emergence, elderly Chinese read Harakah, the Selangor Chinese Town Hall Civil Rights Committee forum features an all-Malay panel, Malays in large numbers attend the “Chinese” Democratic Action Party (DAP) forums, Malays keep a vigil for DAP’s Lim Guan Eng whose defence of an underaged Malay girl led him to prison, and the oft-arrested and severely bashed Tian Chua becomes a hero to predominantly Malay protesters. There was also this perceptive sense of solidarity noted in the entry for 2 February 1999:

“The four of us posed for the camera and, as the flash dazzled my eyes for a moment, it suddenly dawned on me. Here were four people, from four different political parties—Keadilan, PRM, DAP, and PAS. We were standing arm in arm, not giving a damn about our political or ideological differences, but just united in celebrating the birth of yet another force for justice, and joined by a common desire for change in our country.”

Sabri cryptically added, “I hope the picture turns out right.” I don’t know about the quality of the photograph, but six months later, the four opposition parties formed a coalition, Barisan Alternatif (Alternative Front).

Shahnon Ahmad: By virtue of profanity

In fact, by the time Anwar was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment upon his conviction on “Black 14” (14 April 1999), Malay popular opinion and dissident sentiment had stiffened. Reformasi supporters no longer reveled in “alternative media.” They now exulted in the possibility of electing an “alternative government” in the next general election. The most explicit literary exposition of this mood swing came in the form of a novel written by National Laureate Shahnon Ahmad, first published in April 1999.

The full title of the novel is SHIT@Pukimak@PM (A political novel that stinks and creates stinks). The novel is an allegory located, as it were, in the bowels of the human body where bodily waste—in lumps (ketulan), piles (longgakan), and heaps (lambakan)—forms a “shit front” with one powerful lump, “PM,” at its head. Malodorous emanations rise from the body to raise a terrible stink that permeates every nook, cranny, and crack. The way to end the unbearable stench is to expel the turds or to have them leave of their own accord, in either case via the normal “blessed hole” (lobang keramat). But both options are prevented by “PM,” whose followers do nothing but continue “nodding” (angguk) in acquiescence, fearful that recalcitrance will bring swift punishment. As the situation deteriorates, one courageous lump (Wirawan, from wira meaning hero) opposes “PM,” in particular the latter’s “mega project MKKM” (Masuk-keluar keluar-masuk, in-out out-in). So “PM” fixes Wirawan in a conspiracy that ejects him from the sheltered zone of power (kawasan kekuasaan) to be left to the mercy of the “people turds” (ketulan rakyat jelata) composed of the “wind, rain, earth, sun, trees and people.” At that instant, Wirawan, though long alienated from the “axis of popular struggle” (paksi perjuangan rakyat), is cleansed of foulness by the gathering rain, finds popular support, and interjects “a term that he had hitherto kept to himself”: Reformasi! Then comes a Wirawan-led expedition (“Anabasis”) that succeeds in ejecting “PM” to face the popular wrath, leaving Wirawan with the duty of working with the people to pave “a new highway” with “beauty, faith, justice and sincerity” (keindahan, keimanan, keadilan dan keikhlasan).

In the Reformasi milieu, the direct link between the novel’s plot and Malaysia’s tension and turmoil pre- and post- 2 September is immediately recognizable. No savvy reader, Malay, non-Malay, or non-Malaysian, can overlook Shahnon’s barely disguised allusions: the antagonists, “PM” and “Wirawan”; a “stinking and stink-creating administration”; a sycophantic polity inhabited by nodding “yes shits”; the “Zenith Council”; and so on. The text is full of now titillating and thrilling, now offputting and tedious, descriptions of body parts, wastes, fluids, and movements. About the tone of the story, not much needs to be said other than this: it is viciously cynical before becoming, in hindsight, hopelessly wishful. But to read the novel politically is to grapple with its most controversial element, that is, Shanon’s language, and specifically his excessive if not obsessive use of obscenities.

In the lexicon of the novel, “shit” (taik) is arguably the least offensive term, at any rate for squeamish readers. The most offensive word, though perhaps deliciously apt to other readers, is PukiMak. What does the term mean? Neither Sumit Mandal, who observed that “Shit is not easy bedtime reading” (Mandal 1999), nor Farish A. Noor, who considered “Shahnon’s tale [to be] a riot of metaphors, allegories and similes so confused that the reader is left clueless at times to understand what the message of the text is” (Farish 1999), referred to the word at all. Amir Muhammad, predictably too irreverent to ignore the “blistering display of iconoclasm and earthy hyperbole”—“it would take an ass not to respond to the life-affirming humour”—but perhaps limited by the morals of the regional press, called it “a common but harsh Malay expletive referring to female genitalia” (Amir 1999). Yet an unflinching reader would say, “Cunt”—in the tone one uses to say “Motherfucker!”—and be done with it.

Well, one cannot be done with it yet. SHIT was an immediate best-seller: an initial print run of 15,000 copies was quickly sold out. Whatever one thinks of the novel qua novel, its popularity spoke to its effectiveness as an allegory specific to the political circumstances of the day. Part of the sub-title of the novel, busuk dan membusukkan, has been translated as “stinks and creates stinks.” More to the point, Shahnon’s scatological imagery, which relentlessly brings to mind pictures of filth, stench, and waste, evokes a miasma of corruption that has so defiled the body politic that all its institutional organs must be turned inside out for a public cleansing. That Shahnon quite happily spews out some of the most vulgar Malay swear words is partly explained by the author’s admission of a “repressed side” to his personality (Amir 1999). But amidst the rising tide of disgust at the unrestrained media and testimonial revelations of anal penetration, semen, and masturbation, perhaps one National Laureate’s catharsis—what other solution to repression is there?—offered cultural release to a community oppressed by aib (shame).

So along the “alternative information” superhighway Shahnon’s profanity sped and was swiftly, angrily, or joyously adopted as an anti-regime code. PukiMak, sometimes decorously given as P***M**, whether written with or without its aliases, became a favorite word in Reformasi cyberspace (along with “DSAI,” an abbreviation for Dato Seri Anwar Ibrahim). With UMNO’s severe loss of support in the “Malay heartland” in the November 1999 general election, it would seem unnecessary to argue whether a mass Malay readership was “clueless” about the “message” of SHIT.

Khoo Boo Teik

Khoo Boo Teik is an Associate Professor in the School of Social Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, and author of Paradoxes of Mahathirism: An Intellectual Biography of Mahathir Mohamad (Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, 1995).

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 1 (March 2002). Power and Politics

REFERENCE

Amir Muhammad. 1999. “Raising a Stink.” Asiaweek, 7 May. http://www.asiaweek.com/asiaweek/99/0507/feat1.html

Cheah Boon Kheng. 1998. “The Rise and Fall of the Great Melakan Empire: Moral Judgement in Tun Bambang’s Sejarah Melayu.” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 71, pt. 2, no. 275 (December): 103-21.

Farish A. Noor. “From the ‘Taj us-Salatin’ to Shahnon Ahmad’s ‘Shit’: Malay Political Discourse Leaps To A New Radical Register.” http://www2.jaring.my/just/Art_Farish.htm

Mandal, Sumit. 1999. “A Brief Review of Shit.” Saksi 6 (July). http://www.saksi.com/jul99.sumit1.htm

Sabri Zain’s Reformasi Diary. http://www.geocities.com/CapitolHill/Congress/5868