Despite being a signatory to the 1951 UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, increasing domestic anti-immigration sentiment has shifted Australia’s policies towards preventing refugees from arriving in Australian waters before they could claim for asylum.

Indonesia, on the other hand, has not signed any international asylum law, although it had cooperated with the UNHCR in assisting Vietnamese refugees up to the mid-1980s. Indonesia has for long proved to be a weak spot from Australia’s perspective, given evidence by the growth of ‘people smuggling’ syndicates that operate vessels into Australian waters from Java’s and East Nusa Tenggara’s southern coasts. While this implies that the Indonesian government could practically arrest any asylum seeker right away as immigration offenders, the underfunded immigration authorities have become overwhelmed to fund the deportation of increasing numbers of asylum seekers. At another level, most immigration officers interviewed wouldn’t be too bothered, saying that “we don’t have specific laws or orders in handling asylum seekers, so we just send them away to the UNHCR or IOM offices in Jakarta. If we detain them, who would cover their food?”

As a result, at least until 2010, asylum seekers were received very differently depending on the immigration offices throughout the country. In a number of cases, asylum seekers are left to sort out their own onward journey plans, or are referred to the UNHCR or IOM offices. Even a minority were allowed to work, as in the case of a Vietnamese Khmer Krom (ethnic Khmer) family stranded in Batam where females were employed for eight years as housemaids while their husbands converted to Christianity and worked in a local Church. In other cases, Tamil refugees from Sri Lanka were looked after by the local Tamil community in Medan while waiting for their asylum request to be granted. The majority of Afghan and Iraqi refugees, however, employ a two-track strategy that includes submitting a formal asylum request to the UNHCR while simultaneously arranging for ways to enter Australia ‘illegally’ by vessels in case they are not under detention. Many of the latter manage to blend themselves into the burgeoning Arab community in West Java’s Puncak region, not very far from the anchored vessels headed for Australia.

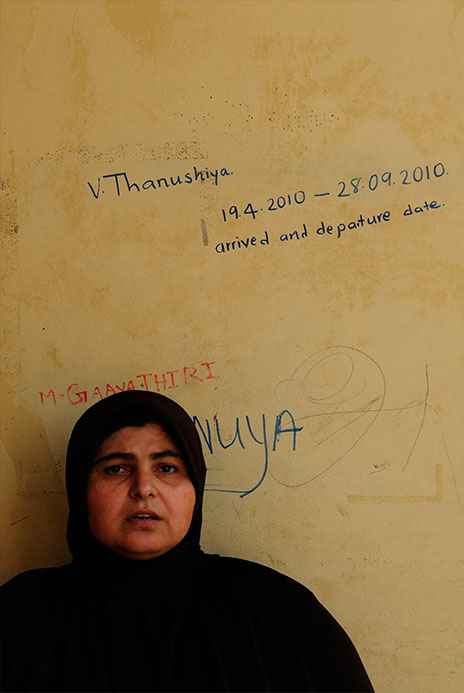

The detention of asylum seekers by immigration offices has been on the increase in conjunction with increased Australian aid in setting up immigration detention facilities. The overcrowding of Indonesia’s low-capacity immigration detention centers in Jakarta and Medan resulted in the additional construction of a new detention center at Tanjung Pinang in the Riau Islands.

Those under detention depend on the duration of the UNHCR asylum request investigation process that may vary from only a few months to a process that may take years. Another problem is the bureaucratic technicalities of categorizing refugees. For example, the Vietnamese Khmer Krom family were not considered by the UNHCR as legible asylum seekers given Vietnam’s current no-conflict status. A large number of young Hazara refugees are closely investigated given that many were actually born and raised in Pakistan’s Balochistan region from parents who have already fled from the first Afghan war in 1979.

The long detention process also brings social consequences. The locking up of large numbers of males is akin to a prison that breeds hierarchy. Young males are sometimes exploited and fall into servitude (including for sex). Being isolated from any information on their eventual release causes many detainees to suffer from psychosomatic symptoms of stress.

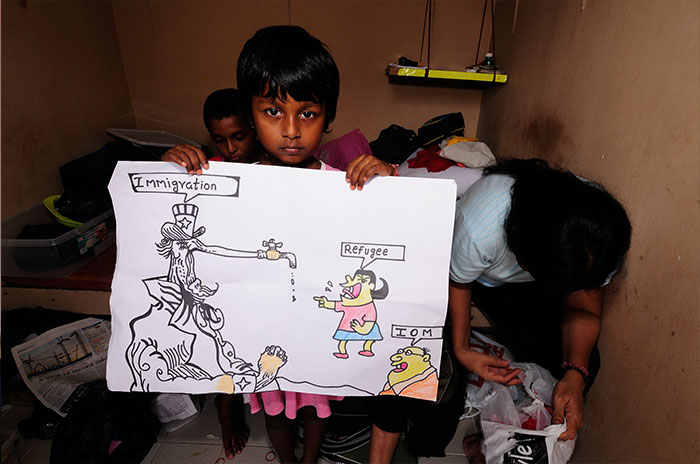

A number of children are raised inside detention centers since their infancy. Having only fellow kids from other nationalities to play with, these youngsters quickly adopt Indonesian language, picked up from Indonesian immigration officers, as their lingua franca.

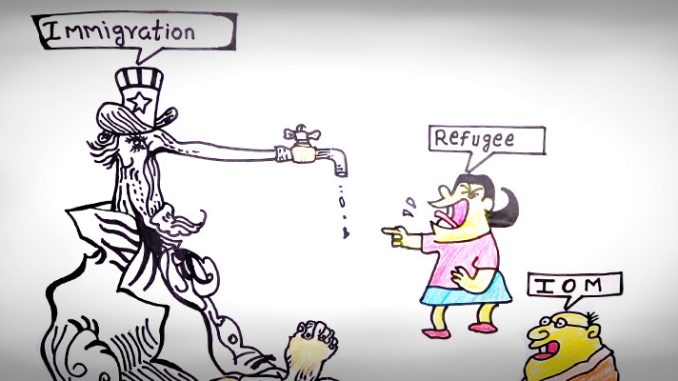

Indonesia is grappling, institutionally, with its new role as an outsourced border regime for a neighbor that is now backtracking its own decision as an asylum-friendly country.

Dave Lumenta, Ph.D.

(Department of Anthropology, University of Indonesia)

[youtube id=”_dPTf2wcgBo” mode=”thumbnail” align=”center”]