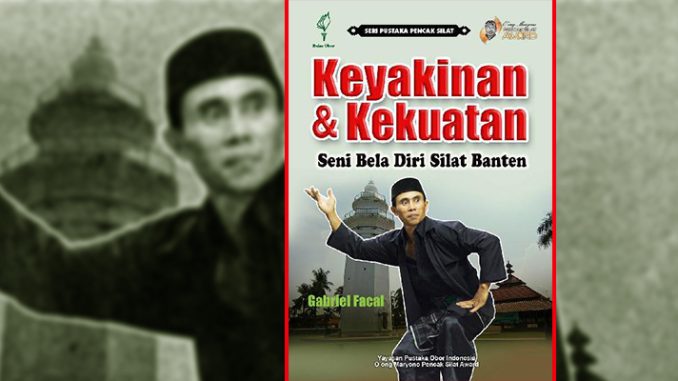

Title: Keyakinan dan Kekuatan: Seni Bela Diri Silat Banten (Faith and Force: The Silat Martial Arts of Banten)

Author: Gabriel Facal

Translator: Arya Seta

Jakarta: Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia and O’ong Maryono Pencak Silat Award, 2016

Keyakinan dan Kekuatan is developed from a Ph.D. dissertation, originally entitled (in French) “La foi et la force: L’art Silat martial de Banten en Indonésie,” written by Gabriel Facal. Facal is an ethnographer and a martial artist who has been practicing in various silat (traditional martial art) schools (paguron) in Banten, Indonesia. Nicely translated by Arya Seta, it was first published in Indonesian to target Indonesian readers.

As its title suggests, there are two unique aspects of the Bantenese Martial Arts: faith (“keyakinan”) and force (“kekuatan”). Facal argues that the interweaving of these two aspects has differentiated Bantenese Silat from other kind of martial arts, even within Indonesia’s regional martial arts traditions.

Strengthening faith is considered the first step to learn silat rituals. After this first step, faith is instrumental to be integrated in the fighting techniques/the forces of the silat. Faith and fighting techniques complement each other in order to gain physical, mental, and moral power, at the same time. Thus, in Bantenese martial arts, both religion and ritual practice are blended and in turn strengthen each other to perfection.

The first part of Keyakinan dan Kekuatan discusses the roots and spread of Bantenese Silat. There was an interplay between silats from different parts of Indonesia: Lampung, Sunda, and Betawi with Silat in Banten. This interplay could be observed from the silat rituals, movements, and breathing techniques. This part also explains the historical development of martial arts in Banten. It was developed by some prominent jawara (silat practitioners) and Kiai (local Islamic leaders) as a tool to defend themselves against the Dutch colonial forces. During the New Order period (1967-1998), many of its jawara and kiai were organized as part of the regime’s quasi-Praetorian guard in the local scene. This pattern still continues, however. In this part, Facal concludes that various rituals in Bantenese silat were influenced by Islam as adapted in local culture. As a result, for the Islamic religious men, it has become a form of devotion.

The second part of Keyakinan dan Kekuatan discusses five main silat schools in Banten: TTKDH (Tjimande Tarikolot Kebon Djeruk Hilir), Terumbu, Bandrong, Haji Salam, and Ulin Makao. These five schools are selected based on the number of its practitioners, geographical coverage, number of branches, and their roots in Banten society.

TTKDH is the most important silat school because of the strong documentation of its techniques, structure and rituals, wide dissemination and its engagement with the world of politics. The story of the TTKDH makes the largest chunk of this second part, that readers can even get a very detailed explanation of its techniques. It is because Facal is one of its members and has trained this school for over 15 years.

Two other schools, the Terumbu and the Bandrong, are the two oldest silat schools in Banten, both are traceable and claim their roots back to the Banten sultanate period. The Haji Salam school is described as a comprehensive submission martial practices and its secret activities. Lastly, the Ulin Makao school is considered as a blend between Silat and Chinese martial art. In his description, Facal explains the history (mostly, based on oral history), techniques, rituals and socio-political aspects of each silat school in Banten.

The differences between each silat school form an interesting comparison to understand its historical roots and also, institutional affiliation. For example, the TTKKDH’s annual ritual of “Keceran” (the dripping of betel water in the eyes of all students, poured through the master’s knife) is the main ritual where all members, regardless of their social class, congregate. A similar ritual is also performed in the Bandrong school, with a different name (known as popobanyu) and the water is poured through a special two-bladed knife that belongs to the Kopassus (Komando Pasukan Khusus/ Indonesian Army Special Forces). It shows the close relationship between some silat schools with the Kopassus.

The third part of Keyakinan dan Kekuatan discusses the characteristics of Bantenese Silat, including the issue of equality among the different schools. It analyzes the spatial and temporal dimensions in technique, the relationship between gender, and also on seniority, and some technical aspects of the silat fight.

The most interesting parts are the social and political aspects of the martial arts itself. The organization of the various schools, within the hierarchy of national, regional and local, has caused some social-political impacts. On the one hand, it brings uniform to all the different silat techniques. On the other hand, it has attracted various schools to build alliances with political parties, religious groups, civil militia, or those who are economically in power. During the New Order period (1967-1998), various silat schools were drawn to support the regime as their patron, so that they could gain benefits from the central government. In the current Reformasi situation, this relationship depends more on the political and economic power of the local patron.

As an anthropological study, Keyakinan dan Kekuatan has offered a deeper understanding on the subject that is important for the studies of contemporary Banten. Studies of contemporary Banten mainly discuss the social and political aspects of the life in Banten, with emphasis on local politics and its political leaders (see for example: Tihami (1992); Okamoto and Hamid (2008)).

Keyakinan dan Kekuatan locates the silat practitioners (jawara) in a cultural context that makes them understood in a more fair and positive perspective. As an ethnographer, Facal has undertaken excellent research that documented valuable information of the Bantenese Silat. Undoubtedly, Keyakinan dan Kekuatan is a must-read reference for any Indonesian who wants to study the rich culture of Banten.

Reviewed by Abdul Hamid

Lecturer at Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa, Banten, Indonesia

REFERENCES

Okamoto, Masaaki and Abdul Hamid. 2008. Jawara in Power, 1999-2007. Indonesia 86: 109-138.

Tihami, MA. 1992. Kiyai and Jawara di Banten, Studi tentang Agama, Magi dan Kepemimpinan di Desa Pasanggrahan, Serang, Banten. Master thesis. Jakarta: University of Indonesia.

How could one write about the details of spiritual, and martial art groups, with government connections? Without raising more than a few angry eyebrows!