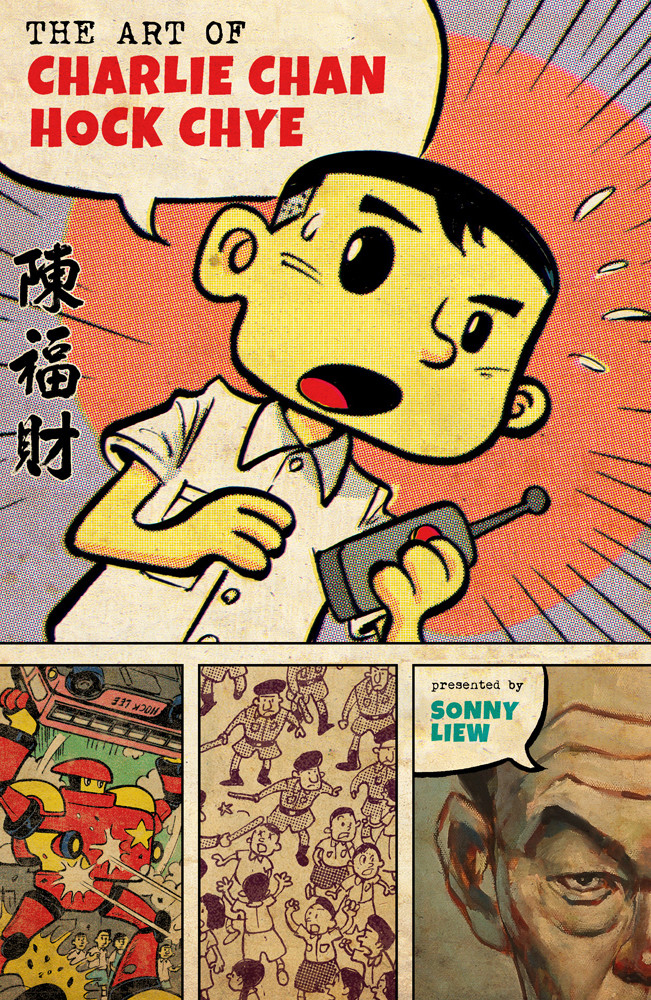

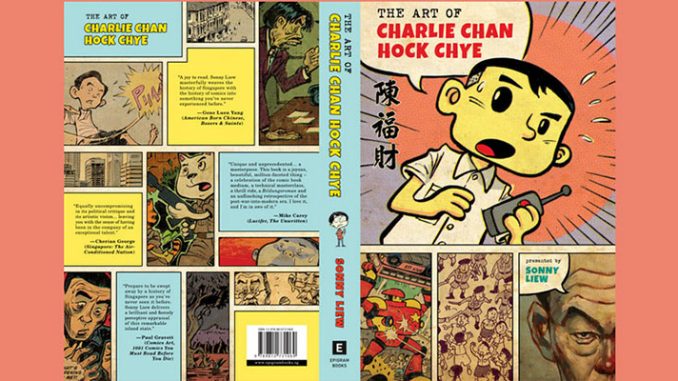

Liew, Sonny. The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye

Singapore: Epigram Books, 2015

The Singapore graphic novel, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye (Epigram Books, 2015), written and drawn by Sonny Liew, was reported in the news recently. Firstly, it was picked up by Pantheon Books for publication in the US and UK for 2016, the first Singapore graphic novel to have its rights bought by a major Western publisher. France and Italian editions are to follow. Secondly, the book was originally given a publication grant of S$8,000 by the Singapore National Arts Council (NAC). After the book was on sale for about a month in Singapore, NAC ‘degranted’ it, citing the politically sensitive content of the book and reclaimed the amount given out. This caused an uproar among the arts community and civil society groups and it was reported overseas as well. The press coverage over this matter led to more curiosity about the book, surging it up the local bestseller charts and it has since gone into its third printing within 3 months, an unprecedented event in Singapore publishing.

At the time of writing, about 3,000 copies of the book have been sold. In hindsight, NAC has done Liew and Epigram Books a favour as the press coverage about the book was worth more than S$8,000. Some cynics joked that this was the strategy to take – apply for a NAC grant and then get ‘degranted’ to receive even more publicity. Controversy sells and there is no such thing as bad news in pop culture.

The hype should not distract us from the fact that The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye is an ambitious, innovative work by an artist who has been experimenting with the medium since the late 2000s. The pudding, as they say, is in the telling. The book adopts the format of art books (ala The Art of Jack Kirby and ilk) and tells the story of the ‘greatest comic artist in Singapore’, Charlie Chan Hock Chye, who never was.

Charlie Chan grew up reading and dreaming about drawing comics. He was influenced by Osamu Tezuka, the creator of Astro Boy, and drew his own boy and robot story for his first comic story in 1954 at the age of 16. A few months later, he was an eyewitness (见证人) to the 513 incident, the student protest against conscription on May 13, 1954, which marked the start of the postwar student movement in Singapore. He drew a comic about that and teamed up with writer Bertrand Wong to create an EC Comics-inspired war comic title, Force 136, which tackled stories about the Japanese Occupation and the Malayan Emergency. Trying to emulate the success of the UK comic weekly, Eagle, their attempt to create Dragon, Singapore’s National Strip Cartoon Weekly, Dragon, did not take off. In 1959, pre-dating Marvel Comics’ revival of the superhero genre, they created Roachman, which could have inspired Spider-man. The stories took from the headlines of the day such as crime, murder, sex and landmark events like the 1961 Bukit Ho Swee fire in Singapore.

After Wong dissolved their partnership in 1962, Chan continued drawing comics (many unpublished) in his spare time while making a living as a security guard. He self-published a few satirical mock posters making fun of government campaigns in the 1980s, but largely his output was unseen by the public.

In 1988, at the age of 50 and after the death of his father, he attended the San Diego Comic Con to seek affirmation from his tribe. He was to be disappointed by the lukewarm response to his portfolio of comics. He returned to Singapore to continue working on his science fiction epic, an alternative Singapore where Lim Chin Siong (the opposition leader of the 1960s) was the prime minister. In 2014, at the age of 76, he continues to work on a new series on Singapore’s position as a financial centre, Dato Duck in Singapore, which is also a tribute to the great duck artist, Carl Barks.

Since the book was published, some academics and comic artists have asked me where is Charlie Chan now and where to find his early books. I shared that Charlie has retired to a small town in Canada, currently undergoing his second divorce. But the good news is that Drawn & Quarterly will be republishing all his books in deluxe editions, edited and with notes by Adrian Tomine.

But that’s a fib. As much as Charlie is a fib. 1 Charlie Chan is a fictional character cleverly used as a framing device to tell the history of Singapore and the struggle of being an artist. Reviews of the book have revealed that some reviewers do not know their country’s own history. Or rather, people are learning history from comic books now. Having researched on the history of comics in Singapore and Southeast Asia, often it is the case that political cartoons and comic strips would appear first in newspapers and magazines. Comic books would come later as it is a commercial enterprise which requires publishers to invest in publishing a monthly title. This would very much depend on the market size, the financial viability of publishing monthly comic books and the maturity of the comic readers to support local titles.

In Singapore, comic books only came about in the 1980s with short-lived titles like Pluto Man and Captain V (although there were single issue examples like Malayan Comic#1 from 1949). The first graphic novel of short stories was Eric Khoo’s Unfortunate Lives and the successful titles were Mr Kiasu and The Celestial Zone in the 1990s and 2000s. Educational comics like Otto Fong’s Adventures in Science series also sell well in the school book circuit. I have written about how most comic artists could not make a full-time living drawing comics in Singapore, and the story of Charlie Chan reflects their plight. 2 Liew himself is an exception as he is published by American comic book companies and he makes most of his money from the West, which affords him the luxury of spending a few years to craft a hefty volume like The Art of Charlie Chan.

The book works at several levels – for the causal reader, for the Singapore history buff and for those who know their comic history. To engage the causal reader, much is invested in building the life story of Chan, a portrait of the artist as a failed man. As a character, Chan is complex as he is flawed – rather obnoxious in his later years (dismissing new comics and yet wanting to read them for free by removing the protective plastic wrapper of graphic novels in bookshops – you know the type), and at times arrogant and delusional in seeing his life in parallel to the political fortunes of opposition leader, Lim Chin Siong. One suspects he is an unreliable narrator in describing the events that happen to him; often he portrayed himself as a victim of circumstances as the world was not ready for his talent.

Chan was someone who could draw in the style of Tezuka, EC Comics, Eagle Weekly, Walt Kelly’s Pogo strip, Jack Davis (MAD) and Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns, and his Roachman comic even pre-dated Spider-man. That should be a clue to the reliability of his claim to be the ‘greatest comic artist in Singapore’.

As for the different comic styles employed, anyone who knows his comic history would know this is a very clever display on Liew’s part to showcase his knowledge of the comic canon for the last 70 years, which leads to the question of the chosen medium. Why use comics and the different comic styles to tell the story of Singapore? I believe the shifting style is intentional – to create an disorienting effect when reading through the text (this is a narrative technique which Liew has previously employed in The Hunt for Mas Selamat in Liquid City Vol 2). It is as if the book is challenging us not to take its text for granted, or any text for that matter. In that sense, having Charlie Chan as an unreliable narrator makes sense. We should not take any text or narrator as a given. Narratives can be destabilized and revised, and for those of us who study Singapore history, we should question our assumptions in the light of new evidence.

Having worked on new aspects of Singapore history, 3 the question for us is how do we present our findings to the public (beyond the academic context) and make it accessible. Liew has shown one way in the unexpected success of The Art of Charlie Chan, helped in some ways by the NAC degranting. When I asked him at a talk in Kuala Lumpur about the potential of comics to shape public opinion, he replied that he hope the book would change people’s views of Lim Chin Siong. This answer shows that so much of the book works because of the resonance it has for readers in Singapore and also in Malaysia. It will be interesting to see how it will be received when it is released in the West next year.

Reviewed by Lim Cheng Tju

Issue 18, Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, September 2015

Read more about the Singapore comic scene in Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, issue 16: Comics in Southeast Asia

Notes:

- Liew first told me about this story idea in 2008 at the first Singapore Toys and Comic Convention. I told him people would be confused by his fake history of comics in Singapore and true enough, that happened. I tried setting him on the path of the straight and narrow by sharing with him my research and archival materials and introducing him to the old cartoonists. But obviously I failed. See: http://www.goethe.de/ins/id/lp/prj/mic/cth/enindex.htm ↩

- See https://kyotoreview.org/issue-16/current-trends-in-singapore-comics-when-autobiography-is-mainstream/ ↩

- http://www.iias.nl/books/university-socialist-club-and-contest-malaya-tangled-strands-modernity ↩