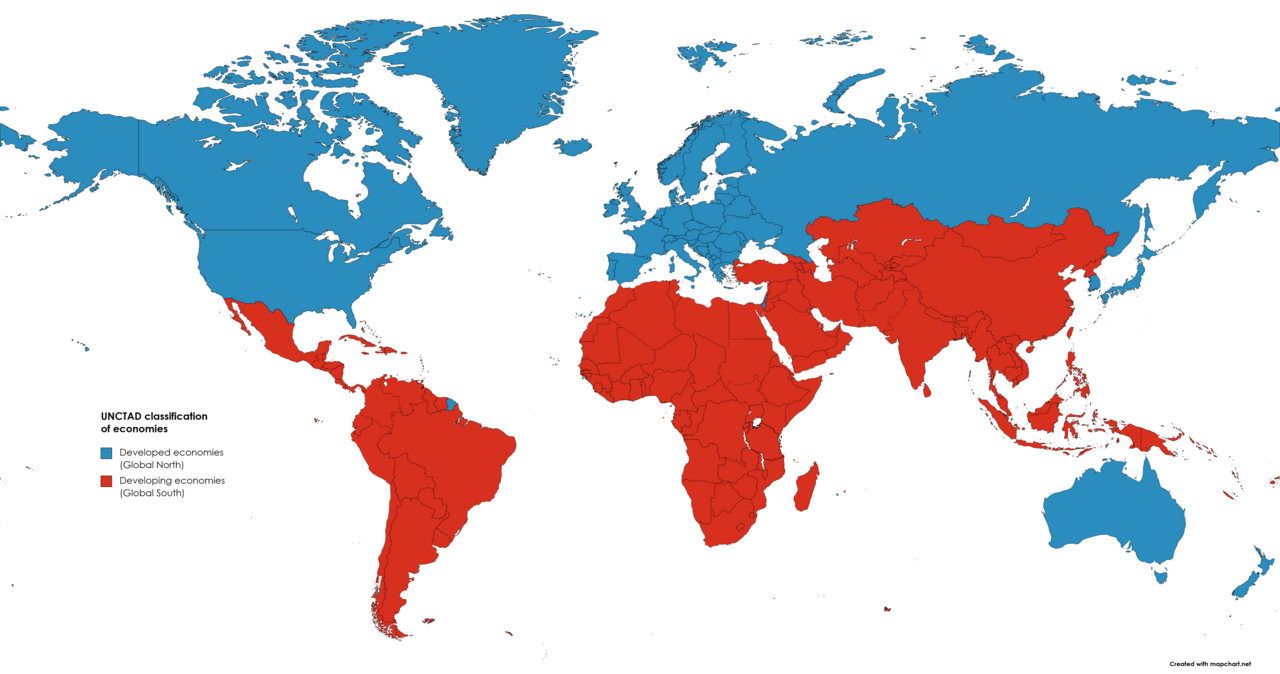

The 2020s have proven to be a tumultuous decade thus far, marked by a global pandemic and subsequent humanitarian crisis in Ukraine and Gaza. Against the backdrop, nations from the “global south” have emerged as vocal critics. In recent years, we witnessed vehement criticism against the uneven distribution of COVID vaccinations, rich countries’ culpability in exacerbating the climate crisis, and the perceived double standards employed by Western powers in international conflicts.

Countries of the “global south” are also trying to shape international relations. A notable development occurred during COP 27 in Egypt, where the establishment of the loss and damage fund, championed by the G77 and China, took center stage. Diplomatic initiatives such as the G20 summit meetings, expansion of BRICS, and Voice of Global South Summit meetings hosted by India have garnered significant attention as potential game-changers. As the influence of the “global south” grows, leaders of the developed nations are increasingly compelled to engage with these countries, particularly in the context of competition with China.

What is “Global South”?

While the “global south” undoubtedly made its voice heard, there remains a significant gap in our understanding on this diverse group of nations. Often associated with the colonial past and developing economies, the term “global south” lacks a universally accepted definition. The ambiguity is underscored by the disagreement between China and India regarding their leadership roles within the group. Despite China’s belief in a co-leadership with India, the latter did not extend an invitation to the former for its flagship Global South Summit. Furthermore, fault lines within the group are evident, as demonstrated by Argentina’s decision to distance itself from BRICS.

While many observers say the “global south” lacks coherence and exhibits diversity, their behaviors are often explained by similar motivations: they take actions to maximize economic gains; they prioritize ties with arms suppliers; they resist taking sides in the great power rivalry. 1

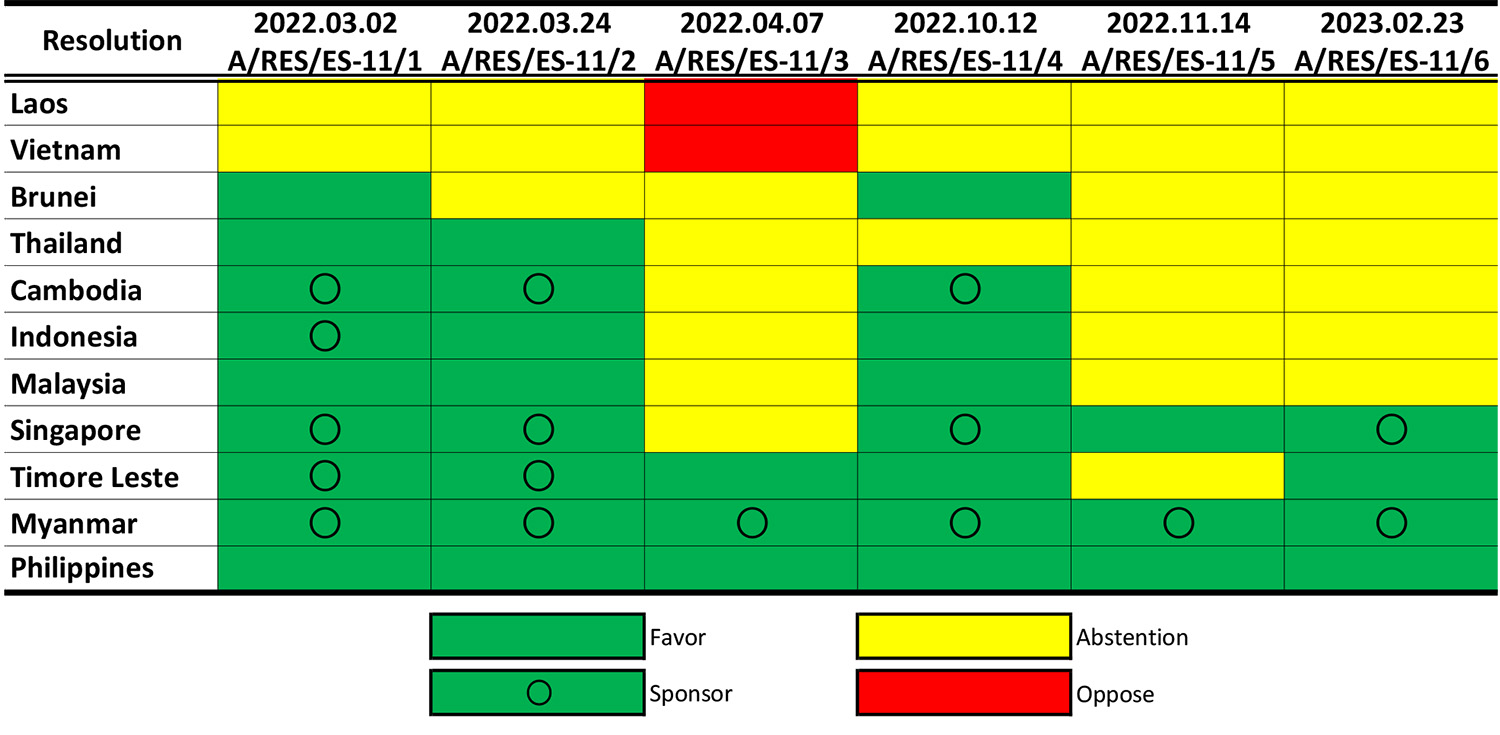

The voting behavior of the Southeast Asian countries in the six UN General Assembly resolutions on the situation in Ukraine appears to defy such simple explanations or categorizations of “not taking sides.” Vietnam and Laos’ heavy dependence on Russia for arms procurement may explain their consistent abstention and opposition. However, this factor does not explain the positions taken by other countries in the region. Similarly, economic ties do not serve as a reliable explanatory factor, as the trade share of Russia and Ukraine is minimal across the region, except Brunei, which imports crude oil from Russia.

Reasons for non-support

Deduction from empirical conditions exhausts. We need to delve into a cognitive domain. Individual states possess unique historical narratives that shape their perceptions of the world and themselves. These narratives imbue their behaviors with specific meanings that cannot be deduced solely from empirical observations. 2 Speeches on the countries’ voting at the UNGA enable us to peep into their ideational perceptions.

For instance, Thailand expressed concerns about the UN becoming an arena of power politics rather than maintaining its intended role as a “transparent, impartial and inclusive … multilateral regime” (A/ES-11/PV.10). In abstaining from the UNGA resolution titled “Principles of the Charter of the United Nations underlying a comprehensive, just and lasting peace in Ukraine” passed on February 23, 2023, Thailand criticized the UN for having become “a part of the morality play that turns very complex situations into simple binaries of good and evil” (A/ES-11/PV.19).

In another instance, the draft resolution “Suspension of the rights of membership of the Russian Federation in the Human Rights Council” (April 7, 2022) received 24 oppositions and 58 abstentions. Countries such as Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia, which abstained from the resolution, argued that an Independent International Commission of Inquiry established under the Human Rights Commission should be allowed to investigate without prejudice. Malaysia, a long-time advocate for the democratization of the UN Security Council, also criticized the Council for its inability to perform the “primary responsibility to maintain international peace and security.” (A/ES-11/PV.19)

Pot calling the kettle black

The draft resolution “Furtherance of remedy and reparation for aggression against Ukraine” encountered 14 negative votes, with 78 countries abstaining. The harshest criticism came from South Africa denouncing “exceptionalism” exhibited by Western nations for having previously opposed “calls for reparations for slavery, colonialism, apartheid.” When Vietnam and Laos emphasized their sufferings in the process of independence, they joined the cries of the countries once dominated and oppressed to seize the opportunity to underscore the historical baggage of the Western nations (A/ES-11/PV.15).

For Muslim nations, the swift actions of Western countries against Russia served as a reminder of their longstanding discontent. Indonesian representative, abstaining from the resolution in February 2023, stated that we “must not apply double standards in addressing situations of conflict…, whether it be the war in Ukraine, in Palestine or in any other part of the world. (A/ES-11/PV.19)

How to deal with the specter of past domination

Countries from the “global south” have expressed their decades-long discontent with the dominance of major powers and the inequality prevalent in international institutions. They have also condemned what they see as moral deficiencies on the part of developed countries. With the growing economic and political influence of the “global south,” these grievances will likely intensify. In its pursuit of support from developing countries, China is poised to leverage these sentiments to its advantage. Over time, this discontent can potentially unite the “global south,” despite its inherent lack of coherence.

Developed countries must acknowledge and address their history of domination more seriously. Otherwise, even the sincerest call to uphold the rule of law by them would be construed as an effort for a status quo, further fuelling discontent and widening the gap between the West and the rest.

SUZUKI, Ayame

SUZUKI, Ayame teaches at Rikkyo University, Japan.

References:

Shidore, Sarang (2023) “The Return of the Global South: Realism, Not Moralism, Drivers a New Critique of Western Power,” Foreign Affairs, August 31, 2023.

Spektor, Matias (2023) “In Defense of the Fence Sitters: What the West Gets Wrong About Hedging,” Foreign Affairs, May/June 2023.

Spryut, Hendik (2020), World Imagined: Collective Beliefs and Political Order in the Sinocentric, Islamic and Southeast Asian International Societies, Cambridge University Press.