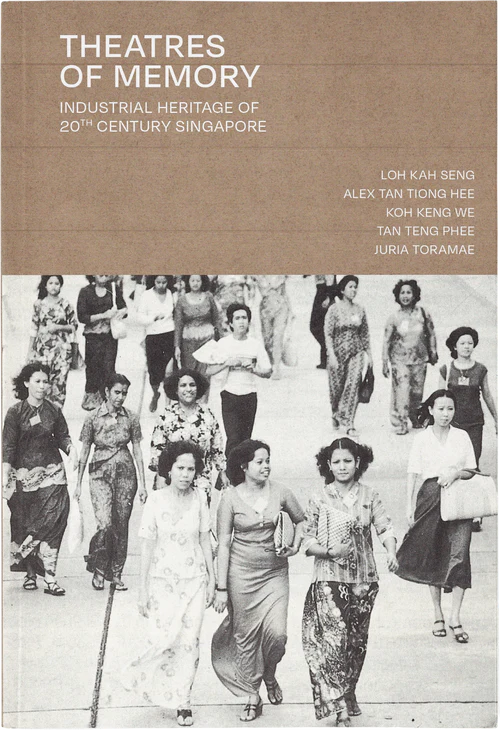

Title: Theatres of Memory: Industrial Heritage of 20th Century Singapore

Authors: Loh Kah Seng, Alex Tan Tiong Hee, Koh Keng We, Tan Teng Phee, & Juria Toramae

Ethos books, Singapore, 2021

Industrial heritage may be seen somewhat as the ugly duckling of heritage writ large. When we think of things, places or practices frequently celebrated as heritage, especially in Southeast Asia, it is not with images of machineries, factories or manufacturing lines in mind. There are many possible reasons for this. It could perhaps be because industrialisation is often seen as the ‘enemy’ of heritage, responsible for the destruction of much of what we held dear growing up. Or because industrial heritage itself does not have a particularly pleasing aesthetic. In fact, looking at the pictures of the industrial sites in the book (that are still standing) itself will not really inspire many, tourists or even locals, to go visit them personally. Third, it might be that the idea of ‘work’ goes against that of recreation and relaxation and therefore not something that is worth exploring during one’s free time.

It is not surprising therefore that there have not been many sites associated with the history of industralisation in Singapore included as sites of historical interest. These sites (and the stories attached to them) have also been given only cursory attention in the nation’s textbooks and Learning Journeys programs where students are encouraged to visit historical sites in Singapore as a way to learning about the Singapore Story, even as these industrial landscapes still lie around us, and figures associated with this moment in our history immortalised at sites like Garden of Fame at Jurong Hill. While there is literature about industrialisation in Singapore, there has not been many that considers this important part of the nation’s history as heritage per se. In this regard, Theatres of Memory, that centres on the social and official history of Singapore’s industrial (r)evolution over time, through archival materials, formal documents, old maps and interviews with relevant players, is a much needed injection into the relatively sparse scholarship related to this topic.

As a scholar of heritage and someone who conducted educational tours to sites such as Jurong Hill (and the Garden of Fame) before Learning Journeys was even introduced in 1998, there is so much I like about this book. More than the fact that it covers an important part of the nation’s history, the book emphasises the many individual actors, institutions and pioneer companies that played important roles in the industrialisation process even as many Singaporeans generally do not know much about them. The book also sheds light on the difficulties associated with industrialising Singapore, from the perspectives of the makers as well as the workers, thus complicating the oft-told story of the whole process as a ‘success’. As the book makes clear, it was one that was frequently mired in conflicts, conundrums and clashes of personalities, not to mention also the myriad challenges that were faced by the people themselves who suddenly had to adapt to a rapidly changing Singapore then.

Herein lies one of the key worth of Theatres of Memory in looking at Singapore’s industrial history not only from the points of view of historians and policy makers but also of the people themselves or the ‘‘little people’ who were deeply involved as pivotal participants of Singapore’s industrialisation, not always voluntarily, but rarely regarded as an equal partner of this remarkable journey. Drawing inspiration from Ralph Samuel’s 1994 book of the same title, that celebrates the (hi)stories of the mundane and the everyday as salient heritage, Theatres of Memory is not just a history of the nation and its formal players but also of the ‘managers, engineers, technicians, clerks and regular production workers’ (page 6). This was accomplished primarily through archival materials and oral interviews, and provides us with a window of what may be referred to as ‘heritage from below’ often written out of formal histories and heritage. In doing so, the book therefore highlights the under-rated value of oral history which does have the potential to really provide a deeper and still critical understanding of the past beyond merely through the eyes of the elite makers of history. The use of social media in the book as a method of data collection is also highly creative.

I also appreciate this book as one about places no longer in existence, and scenes and practices no longer visible. As a Singaporean, I read the oral histories with much interest about how Singapore’s industrial landscapes have evolved over time and how these were the result of changing work cultures and practices, such as through the development of machines and other industrial tools. Fortunately, as the authors mentioned, ‘though the buildings may have disappeared, people’s memories often have not’ (page 5). As I leaf through these pages, I also found myself pondering about places like the Jurong Open Air Cinema, even as I was not even born then, and how places like Teban Gardens got their names (see Chapter 3). Finally, the value of Theatres of Memory lies in its focus on groups that are often disenfranchised in national histories, in this case that of the women and industrialisation (Chapter 4) and the foreign workers in contemporary Singapore (Chapter 10). This makes the book more than just a history book; it is a call to social justice as we better hear the voices of those written out of national historiography and history books.

Theatres of Memory therefore is something I hope that everyone (especially Singaporeans) would read. This is not to say there were things I wished the book had done more of. For instance, as the authors also realised, the book focuses primarily on the 1960s to the 1990s without considering what happened before, such as from the perspective of industrial archaeology. I would have also liked to see more on what Jurong was like in the past before it was industrialised: for instance, who lived there? How were their lives changed due to the transformations of Jurong? What happened to these people? Finally, I am missing more consideration of the ethnic question. I imagined that the cultures and experiences of work for the Malays, Chinese and Indians would differ although this has not really been systematically dissected in the book. Having said that, this book was an insightful read and makes a good start on an important topic. My final hope is this will jolt more to think about industrial heritage as less of the ugly duckling it was before to the beautiful swan it truly is.

Reviewed by Hamzah Muzaini

Hamzah Muzaini is assistant professor at the Department for Southeast Asian Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, National University of Singapore.