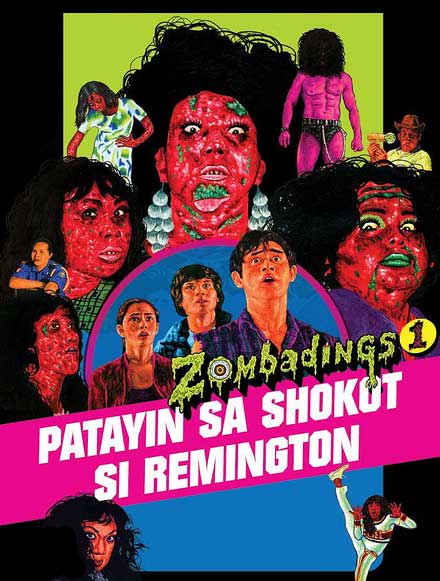

Zombadings 1 :Patayin Sa Shokot si Remington

[Remington and the Curse of the Zombadings]

Directed by Jade Castro (2011)

Zombadings (or Patayin sa Shokot si Remington) is a spoof on comics culture. It is also a fairy tale romance set in the town of Lucban. Essentially it is a coming of age comedy about a little boy, Remington (he begins very young indeed) yelling out loud whenever he notices the queer behavior of local town shokis – the historical term in the 50s and 60s for queer kids. Remington, alert to spot abnormal looks and behavior, unable to understand quirky and queer mannerisms, is the town crier who bellows “Bakla!” (Gay) instead of “Tulong!” (help) at every boy, teenager, or passer-by that crosses his gaze. In the world of fairy tales, he is the little boy in “The Emperor’s New Clothes” who pinpoints and articulates reality. He is yesterday’s gay-dar.

So it comes to pass one day, on a visit to the cemetery, Remington spots a figure in gray, bejeweled with an oversized magenta scarf, and dressed to the nines in over-the-top Rudy Dandan imitation outfit sewn by a local costurera (seamstress), grieving quietly in front of a grave. Remington, on cue, quickly hollers his juvenile mantra. The mysterious lady (played with extra relish by Roderick Paulate) turns placidly to him and spews out a cobra curse of a lifetime, stunning the poor little boy into silence: that one day, he will end up queer! Jump to the present: Remington is now a high school student. He falls in love with a visitor, or a fellow kababayan (Filipino national or town mate) on vacation from Manila, a pretty girl, Hanah (Lauren Young), who is the daughter of a recently widowed mother (Eugene Domingo), come back to take up residence once more in the province. Remington gets hired to help restore their house to living condition.

Meanwhile, the town, Lucban, is overrun with strange occurrences. The town manicuristas (beauticians) in a series of unsolved murders, are discovered, burnt by a mysterious serial-killer. The cadavers have one uniform look, electrocuted into a leprous state of shock, coiffed in rich afro hairdos. The police and town mayor are, what else, perplexed.

The main plot of the movie is Remington’s growing attraction to the city girl, Hanah. As his attraction and desire increases, the curse proportionately works on him via daydreams and images of confusion and distraction that pull his behavior into the world of bekemon, the most current patois of gay language, which used to be called sward-speak. At its current development of sophistication in vocabulary—what used to be recognizably a language of repressed neurotics inventing terms for emotional release, bekemon has become Esperanto—a new language that deserves punctilious translation into grammatically correct Cinemalaya English subtitles. It is probably meant as a joke by the producer-writers, but works against the comedy. Eugene Domingo has to explicate it when she utters, “I don’t understand it. But it is funny.” In the process, the humor is dissipated into awkwardness, and repartees are made lame, killing tempo and rhythm. Remington is drawn to speak and behave like a teenage boy gradually losing control over his maleness into queerness, climaxing in a funny fantasy love scene on a staircase with his best friend, Jigs (Kerbie Zamora). The two male lead characters, Martin Escudero and Kerbie Zamora are very good, because at this early stage in their careers, they’re fresh, unmannered, and still un-self-conscious! So they succeed in giving the impression that they’re not acting, just being themselves. Martin’s quick shifts from queer to manly is hilarious! Kudos to the director.

The Zombading murders are hinged on an invention by a scientist from Los Banos, who creates a gun-radar that can diagnose hermaphrodites in pigs and other animals. The gun is stolen and used on unsuspecting beauticians. (Strange, no couturiers are victims!) The story telling is at best unwieldy with numerous subplots and detours on town characters. Its labyrinthine narrative will one day be probably termed stylishly Pinoy, but one wished the director and writer were less lost in their material and more focused in the telling. The rhythm and tempo of the whole enterprise suffer from excessive kwentuhan (chatting) and parenthetical “by-the-way” episodes. The comedy would really benefit from more focused editing and tightening of the plot. Perhaps the producer, director, and writer were wary of the fact that their plot is so thin and insubstantial that they opted for palabok (flowery speech or unnecessary detours in story-telling) and endless digressing to create a sleight-of-hand effect. After all, this is not a film about truth, but a movie about having fun on the way to becoming an adult. The boy becomes a man by experiencing the thing he fears most: turning queer. But he indulges in queerness as a way to shake off his cursed demon/paranoia. Simple lang (It’s that simple!).

The Zombading murders are hinged on an invention by a scientist from Los Banos, who creates a gun-radar that can diagnose hermaphrodites in pigs and other animals. The gun is stolen and used on unsuspecting beauticians. (Strange, no couturiers are victims!) The story telling is at best unwieldy with numerous subplots and detours on town characters. Its labyrinthine narrative will one day be probably termed stylishly Pinoy, but one wished the director and writer were less lost in their material and more focused in the telling. The rhythm and tempo of the whole enterprise suffer from excessive kwentuhan (chatting) and parenthetical “by-the-way” episodes. The comedy would really benefit from more focused editing and tightening of the plot. Perhaps the producer, director, and writer were wary of the fact that their plot is so thin and insubstantial that they opted for palabok (flowery speech or unnecessary detours in story-telling) and endless digressing to create a sleight-of-hand effect. After all, this is not a film about truth, but a movie about having fun on the way to becoming an adult. The boy becomes a man by experiencing the thing he fears most: turning queer. But he indulges in queerness as a way to shake off his cursed demon/paranoia. Simple lang (It’s that simple!).

The film has no mission. It neither works out character with any real depths or breadth. They all remain essentially cardboard characters. It is not a gay libbers’ opus to help society become more tolerant. The town of Lucban is portrayed in the end as a home of zombies (zombadings)—all queers zapped into a new state of being. In their newfound state of life, they are even organized into a community factory of hat weavers giving competition to the world famous Cabuncals, who as hat makers, are worldwide suppliers of buntal hats. It is a confusing statement. Are the producers saying all gays in this town are ugly but productive when zapped out of neurosis? What will the Freudians and Marxists say? What will Professors Danton Remoto and Neil Garcia say ex-cathedra? I dread fearsome intellectual repercussions.

Zombadings does not pretend to reflect truth or reality by way of character delineation. It is instead a celluloid kundiman (Filipino love songs) on cinematic clichés and comics mythology as appropriated Hollywood folklore. It is a contemporary attempt at reinventing juvenile folk art from fast disappearing in the avalanche of 21stcentury internet-game culture.

Reworking clichés is not necessarily a bad thing. It is fun, fun, fun. And the efforts of Raymond Lee (producer/writer), Michiko Yamamoto (writer), and Jade Castro (director) are rewarded with a box office jackpot. It confirms a formula that the cinema is not for the burgis (the middle class). Neither is it for the “C & D audience” (low I.Q. audience). Rather it targets (just like current Hollywood blockbusters) everyone with a nine year old mental capacity—all the Peter Pans who wish to indulge in local nostalgia, re-living the Hollywood B movies of the ‘40s and ‘50s as reflected in comics imagery of the Mars Ravelo school.

When local columnists rave about this production, proclaiming that it is a runaway hit that kept them laughing from beginning to end, one pauses with a double take. Unless they are investors in the production and are doing a hard-sell, one asks: Was it all that hilarious? Seriously now! There were many charming moments, and selected episodes prompting chuckles, but the confusion in the story telling especially in the latter part of the movie refused to accelerate into a roller coaster ride of screwball comedy that it so promised to deliver.

The climax for all the intellectuals, in case you missed it is, is, IZzzzz… the scene where the boy gets girl. “Nashokot talaga akrils! Akala ko talagrace di mageching ni Remington si Hanah!” (In hysterical tone: I was absolutely terrified! Really, I thought Remington would end up without his darling Hanah!) Was this a gay movie? As gay as Onnagata!

Reviewed by Nonon Padilla

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 12 (September 2012). The Living and the Dead