This paper presents a “trimmed” version of the “Media Co-optation Toolbox” crafted by Freedom House to explain how President Rodrigo Duterte has kept Philippine mainstream media organizations in check by employing economic/legal and extra-legal and means to demand submission or silence from journalists. The middle part of the paper discusses how pro-Duterte bloggers and supporters in social media have undermined the credibility of Philippine mainstream media organizations by producing and spreading narratives on key issues which oppose established political norms and bodies of discourse often labelled as “fake news” or alternative truths. Finally, the paper examines some of the issues surrounding the so-called “bias” of Philippine mainstream media organization against the government in general, and the Duterte administration in particular. It will also look into the Philippine mainstream media’s attempt to co-opt government through the “eclipse of influence” by media bosses and the collusion or cooperation of newsroom personnel.

Article Sections

The Philippine Media: A briefer

lliberal democracy and the media

Duterte’s :”trimmed” co-optation toolbox

– The toolbox ‘repairs’ the media

– Government-backed ownership takeover

– Arbitrary tax investigations/ other cases

– Verbal harassment

– Smear of proxies

Is Philippine Media illiberal?

– Duterte as Philippine media’s echo chamber

– Media co-opting the government?

– “Experts” as enemies of smear proxies

Conclusion

Introduction

“We need to talk about Rodrigo Duterte,” bore the opening line of sociologist Nicole Curato’s essay 1 which carried the same title, a year after President Rodrigo Duterte came to power. It’s hard not to talk about the president these days, especially with a dynamic media closely following and recording Duterte’s move, mood, and mouth. Unlike his predecessors, the Davao City leader spared no honeymoon period with the immensely critical Philippine media. With verbal guns blazing, Duterte immediately launching a rapid-fire salvo of insults and expletives against the “biased” and “bayaran” (paid-hacked) media, for distorting Philippine reality in favor of their oligarch bosses.

For a long time, no Philippine president has openly talked about the media as a willing and convenient arm of the political elite, let alone the filthy rich among its ranks. But Duterte is on a league of his own. And we need to talk about him — and his strained relationship with the Philippine media. This paper will discuss how Duterte captured public opinion by pinning down some of the country’s top media outlets through a “co-optation toolbox” inspired by the model of international watchdog Freedom House to analyze how Hungarian president Viktor Orban and Serbian prime minister Aleksander Vučič utilized challenged and emasculated the Fourth Estate in their respective countries. Freedom House designed this model to describe the co-optation process in “illiberal” democracies such as Hungary and Serbia. Orban’s regime was deemed successful, with Vučič not far behind, in employing the co-optation toolbox, based on Freedom House’s Freedom and the Media 2019 report. The toolbox, according the Freedom House, is now “ready for export.” But not for the Philippines, which actually had a crude version of media co-optation under Ferdinand Marcos’s regime. Duterte, as a self-confessed Marcos admirer, went a notch further by running a “trimmed” yet equally potent, if not more dangerous model than that of the Orban-Vičič version.

The paper will cite instances where Duterte exhibited, or attempted to exhibit, the co-optation model against certain media entities in the first three years of his presidency. It will also show how Duterte successfully marshalled public support among Filipino social media users to fight the “biased” and “bayaran” (paid-hacked) mainstream media firms, based on Facebook data from a news organization with a moderate or neutral relationship with the administration. On the part of the media, the watchdog and muckraking principles of journalism will also be examined in relation to Duterte’s illiberal brand of democracy. Yet in order to understand the uneasy relationship of government and media in the Philippine setting, this paper will likewise highlight key historical moments that ushered in the growth and evolution of the country’s highly Westernized press and its role in a liberal democracy.

The Philippine Media: A briefer

Philippine media arguably began with the Spanish-era Ilustrados’ campaign for reforms, and later separation from the imperial government. These fine men of wealth and letters established the Propaganda Movement as scholars and journalists in Spain. Schumacher said most of them were creoles and mestizos from well-to-do families, underscoring the elitist roots of Philippine journalism. The cultured and educated Ilustrados weaponized the written word to expose the excesses of the colonial administrators and friars in the Philippines.

Among those who typified the overseas political struggle with their pens and persuasion were Graciano Lopez-Jaena, Marcelo H. Del Pilar, Jose Rizal, Gregorio Sanciangco, Antonio Luna, and Mariano Ponce. La Solidaridad became the foremost platform of the Propaganda Movement in Spain. From Lopez-Jaena as its first owner-editor, the Sol fired satirical commentaries against the corrupt and inept Spanish regime back home. Del Pilar later raised the ante when he assumed the editorship of the paper on December 15, 1889. He drew well-crafted pieces from Rizal, Luna, and the others, who primarily responded to every insult and misrepresentation the Spaniards threw at the indios. Historian and journalist Jesus Valenzuela described the Sol as a repository of “reforms advocated by the Filipinos” and as a means to air their grievances:

It disseminated information about the Philippines. It worked against the monastic order, and defended the rights of the Islands, such as their right of representation in the Spanish Cortes. It campaigned for equality of Filipinos and Spanish soldiers, secularization of parishes, expulsion of friars, civil government, and freedom of the press… La Solidaridad sowed distrust against Mother Spain and the authorities in the islands. (Valenzuela, 1933, 93)

This was arguably one of the earliest manifestations of the Western concept of press freedom which the ilistrados learned and imbibed while living in the highly liberalized 19th century Europe. In the Philippines, the Katipunan also published its own newspaper, Kalayaaan (Liberty), under the editorship of Emilio Jacinto. It basically shared the Sol’s objectives, but it cleverly involved another player – Japan. The Katipunan made it appear that the paper was printed in Yokoyama, Japan to draw the attention of the Spanish authorities. Japan at the time was an emerging regional power, and a declining Spain had to manage the Kalayaan issue cautiously, lest it risks war with the East Asian empire. With a phantom ally in Japan, the Katipunan kept Spanish persecution of the natives at bay, until the colonial government uncovered the Kalayaan ruse. The paper eventually folded, but the passion to expose the abuses of the Spanish authorities was never lost among the ilustrado writers at the time. Luna took the cudgels and mounted La Independencia on September 3, 1898 with the Filipinos already liberated from Spain, making it the “first out-and-out nationalist paper.” Politically, it was considered as the first “Philippine newspaper” because it was founded when the country was already an independent nation. Valenzuela called La Independencia as the “first paper in which the Filipinos expressed freely their own ideas, since following their victory, Spanish censorship was abolished.” La Independencia’s political goal is well ascribed in its maiden editorial:

We advocate the independence of the Philippine islands because it is the inspiration of this country which now has come of age. When a country stands up, like a man, to protest with arms against injustice and oppression, that country shows vitality to live freely by itself. The organs of injustice and government have already been functioning for three months after an arduous battle. We are treating our prisoners of war as any other civilized nation should treat prisoners of war. (Valenzuela, 1933, 101)

Press freedom, which the ilustrados so passionately demanded and fought for against the Spanish colonizers, officially became part of Philippine law under the Malolos Constitution, ratified on January 21, 1899. It was enshrined in Title IV, Article 20, Paragraph 1: “Neither shall any Filipino be deprived:Of the right to freely express his ideas or opinions, orally or in writing, through the use of the press or other similar means.” The Americans conquered the islands thereafter. But this did not stop Filipinos from engaging in journalism. A number of newspapers continued to espouse the anti-establishment but pro-Filipino legacy of journalism introduced by the ilustrados despite American censorship. They sought to offset or negate the influence of government-sponsored newspapers and its pro-American reportage during the US occupation of the country. But the most notable of the flock was El Renacimiento.

Established on September 1, 1901, the paper was deemed a cut above the rest for its scathing reports against the interlopers. Valenzuela described it as a “militant and aggressively anti-American newspaper just as La Independencia was inveterately hostile to the Spaniards.” Its most controversial work, “Aves de Rapina” (Birds of Prey) accused then secretary of the interior Dean C. Worcester of corruption for influence-peddling in big businesses despite holding a sensitive position in the Philippine Commission. The editorial alluded to him as “men who, besides being eagles, have the characteristics of the vulture, the owl and the vampire.” But the clue to the Worcester reference was the mention of “scientist” in the piece, noting that the American official was also a zoologist.

Presenting himself on all occasions with the wrinkled brow of the scientist who consumes his life in the mysteries of the laboratory of science, when his whole scientific labor is confined of dissecting insects and importing fish eggs, as if the fish eggs of this country were less nourishing and less savory, so as to make it worth the while replacing them with species coming from other climes. (Torres, 2008)

The editorial then went on to detail Worcester’s alleged self-serving and illicit business affairs at the expense of the US government and the Filipino people:

Giving an admirable impulse to the discovery of wealthy lodes in Mindoro, in Mindanao, and in other virgin regions of the Archipelago, with the money of the people, and under the pretext of the public good, when, as a strict matter of truth, the object is to possess all the data and the key to the national wealth for his essentially personal benefit, as is shown by the acquisition of immense properties registered under he names of others.

Promoting, through secret agents and partners, the sale to the city of worthless land at fabulous prices which the city fathers dare not refuse, from fear of displeasing the one who is behind the motion, and which they do not refuse for their own good.

Patronizing concessions for hotels on filled-in-land, with the prospects of enormous profits, at the expense of the blood of the people.

Such are the characteristics of the man who is at the same time an eagle who surprises and devours, a vulture who gorges himself on the dead and putrid meats, an owl who affects a petulant omniscience and a vampire who silently sucks the blood of the victim until he leaves it bloodless.

It is these birds of prey who triumph. Their flight and their aim are never thwarted. (Torres, 2008)

Worcester sued the paper for libel and won the case against the paper’s editor Teodoro M. Kalaw, and publisher Martin Ocampo, who were both jailed and slapped $30,000 in damages. The US and the later Philippine Supreme Courts affirmed the decision on February 27, 1912 noting that “the said editorial relating to the misconduct and bad character of the plaintiff is false and without the slightest foundation in fact.” A crucial part of the decision read as follows:

That this editorial is malicious and injurious goes without saying. Almost every line thereof teems with malevolence, ill will, and wanton and reckless disregard of the rights and feelings of the plaintiff; and from the very nature and the number of the charges therein contained the editorial is necessarily very damaging to the plaintiff.

That this editorial, published as it was by the nine defendants, tends to impeach the honesty and reputation of the plaintiff and publishes his alleged defects, and thereby exposes him to public hatred, contempt, and ridicule is clearly seen by a bare reading of the editorial.

It suffices to say that not a line is to be found in all the evidence in support of these malicious, defamatory and injurious charges against the plaintiff; and there was at the trial no pretense whatever by the defendants that any of them are true, nor the slightest evidence introduced to show the truth of a solitary charge; nor is there any plea of justification or that the charges are true, much less evidence to sustain a plea (Worcester v. Ocampo, Kalaw, et al., 1912).

But Governor Francis Burton Harrison pardoned Kalaw and Ocampo before they could even serve their sentence in 1914. The El Renacimiento case was the first of its nature in the country which served as an acid test to Act No. 277 or the Libel Law 2 enacted on October 24, 1901 by the Philippine Commission under William Howard Taft. On November 4, 1901, Act No. 292 3 which covered the crime of sedition, was passed. The American authorities transformed these laws as censorship tools to keep the Filipinos in check, even as Washington expressly upholds press freedom as a fundamental legal right. After the Malolos Constitution, press freedom remained a part of the law of the land with the passage of the Philippine Organic Act of 1902 which also created the Senate and the House of Representatives. It stayed as a basic right beginning with the 1935 Constitution (Article III, Section 1, Paragraph 8) when the Commonwealth government was inaugurated under President Manuel Quezon, who also initiated the founding of the Philippine Herald, the first English newspaper run by Filipinos, when he was still Senate president.

English was extensively taught under the Commonwealth period, subsequently replacing Spanish as the foremost second language of the Filipinos. This development marked the upsurge of more English-language newspapers that intentionally or inadvertently promoted American, if not Western, values and ideas among the reading public. Censorship was technically abolished under these laws. Professional journalists and press freedom received more safeguard with the enactment of Republic Act No. 53 which “exempts the publisher, editor or reporter of any publication from revealing the source of published news or information obtained in confidence” unless it involves national security. Senator Vicente Sotto, a former newspaper man, authored the law which was passed on October 5, 1946. The present nature of Philippine newspapers received much of its character from American journalism. The eight-column banner, physical make-up, the mechanics of headline writing, and the standard style of news presentation are characteristically American (Valenzuela, 1933, 177).

Save for a few hitches along the way, the Philippine press was also credited for bolstering the image of notable men in government; a few of them even became president. One of them was Ramon Magsaysay, who was projected by newsmen covering his campaign sorties as a man of the masses, not to mention the overseas mileage he received as Washington’s candidate under the tutelage of former CIA operative Edward Landsdale. His predecessor Elpidio Quirino was not as fortunate, with the press ratting on his administration’s alleged extravagance underscored by his supposed possession of a “golden arinola” (chamberpot), which did not exist in the first place. Diosdado Macapagal was projected by news reports as a success story, even gaining the monicker “poor boy from Lubao.” But the press later slammed his administration for allegedly covering up the Harry Stonehill smuggling issue. A number of top officials, even Macapagal himself, were reportedly in the American businessman’s payroll through a so-called Blue Book. Newspaper columnists questioned why Macapagal opted to deport Stonehill instead of facing trial in a Philippine court. The press also pitted Macapagal in a “clash of topnotchers” against Ferdinand Marcos for the 1965 presidential elections. Marcos, the 1939 bar topnotcher, defeated Macapagal, the 1936 bar topnotcher.

Marcos would then change the Philippine media landscape when he declared Martial Law on September 21, 1972. In his Letter of Instruction No. 1, Marcos ordered Information Minister Francisco Tatad and Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile to stop the operation of privately owned media facilities and communications. The president stressed the need to keep newspapers and broadcasting outlets from conspiring with anti-government forces, particularly the communists and the opposition, at the time of “national emergency.” His letter explained it in detail:

In view of the present national emergency which has been brought about by the activities of those who are actively engaged in a criminal conspiracy to seize political and state power in the Philippines and to take over the Government by force and violence the extent of which has now assumed the proportion of an actual war against our people and their legitimate Government, and pursuant to Proclamation No. 1081 dated Sept. 21, 1972, and in my capacity as commander-in-chief of all the armed forces of the Philippines and in order to prevent the use of privately owned newspapers, magazines, radio and television facilities and all other media of communications, for propaganda purposes against the government and its duly constituted authorities or for any purpose that tends to undermine the faith and confidence of the people in our Government and aggravate the present national emergency, you are hereby ordered forthwith to take over and control or cause the taking over and control of all such newspapers, magazines, radio and television facilities and all other media of communications, wherever they are, for the duration of the present national emergency, or until otherwise ordered by me or my duly designated representative. In carrying out the foregoing order you are hereby also directed to see to it that reasonable means are employed by you and your men and that injury to persons and property must be carefully avoided (Marcos, 1972).

On September 23, 1972, the military arrested media and opposition leaders critical of the Marcos administration. They were interrogated for their alleged complicity with the so-called enemies of the state, particularly left-leaning organizations and Communist rebel groups like the New People’s Army. More than a year after, Marcos issued Presidential Decree No. 36 which cancelled the franchises and permits of all media facilities allegedly involved in overthrowing the government. It also established the Mass Media Council whose sole power is to grant authority to newspapers, radio and TV companies before they could operate. With Martial Law, publications allowed to operate were limited to those controlled by persons identified with or close to the Marcos administration. Among them were the Philippine Daily Express of Roberto Benedicto, Times Journal of Gov. Benjamin Romualdez, Bulletin Today of Hans Menzi, and Evening Post of the Tuveras (Ofreneo, 1984, 136). Marcos would later explain before high-ranking officials of the Department of National Defense and the Armed Forces of the Philippines, his decision for closing a number of media outfits, particularly those critical of his administration:

The weapon of media has been used to undermine the people’s faith in the government, to destroy society by spreading rumors and speculations that will rock the foundation of any organized society. This is the reason for what you know see, for preventing media from further undermining the faith of the people in our society. This is the reason, I repeat, for taking over some radio-television stations. This is a preventive measure. (Marcos, 1972, 14)

Four months later, the president ordered to penalize “rumor-mongering” or the dissemination of false news and information and gossip which undermines the stability of government” through Presidential Decree No. 90. Marcos also lashed at the money-making schemes of some newsmen, including those whom he perceived as enemies. In a “White Paper” published by the Bulletin Today, Evening Post and Business Day on October 6, 1977, Marcos through the Philippine Council for Print Media Special Committee on Ethics led by Kerima Polotan Tuvera called out these journalists for selling their profession in exchange for a number of “blandishments,” which “include free passes, wining and dining, pocket money given during press conferences, regular “envelopes,” monthly retainers, stocks and bonds, dollars, airplane tickets, expensive gifts (including cars), money-making projects (such as the preparation of anniversary brochures in exchange for handsome allowances and per diems), jobs for relatives, unlimited access to airports, seaports, and Customs (thus facilitating the lucrative entry of highly dutiable items)” (Ofreneo, 1984, 143). From September 21, 1972 until the lifting of Martial Law on January 17, 1981, Marcos came up with 12 Presidential Decrees related to the media.

But Marcos’ shackling of the press did not end there. On December 2, 1982, he ordered the military to seize the WE Forum magazine for its alleged involvement to “overthrow the government through black propaganda, agitation, and advocacy of violence.” Interestingly, the paper which has been publishing opposition-laced commentaries as well as anti-imperialist stories since December 1976, was only padlocked six years after. What really triggered the clampdown, according to some sources, was a series of articles by Bonifacio Gillego (who is identified with the US-based Movement for a Free Philippines) placing the authenticity of the Marcos war medals and therefore the latter’s much publicized war exploits in grave doubts (Ofreneo, 1984, 150). Marcos’ dismantling Martial Law emboldened a group of independent news organizations to continue the struggle, following the WE Forum incident. Collectively known as the “mosquito press,” for their biting criticisms on the regime’s abuses, these independent media players gained more public support after the assassination of former senator Benigno “Ninoy” on August 21, 1983. Less than three years after, Marcos was ousted and the country’s democratic apparatus was restored in the 1986 EDSA People Power. The press was also liberated from years of state-sponsored repression.

President Corazon Aquino immediately repealed what she perceived as Marcos’ anti-media and anti-expression laws. But Cory herself was not fond of the media. On October 1987, she filed a libel suit against journalist Luis Beltran, who wrote in his column that the lady president “hid under her bed” while renegade soldiers shelled Malacañang during a coup attempt in August. Beltran and his publisher Max Soliven, a close friend of Ninoy, were convicted of libel but before they could serve their sentence, the Court of Appeals reversed the decision on July 12, 1993.

The next biggest challenge for local newsmen would later come with President Joseph Estrada’s P101 million libel suit against The Manila Times. The paper’s February 16, 1999 report said Erap brokered a P17-billion power contract between an Argentine firm and the National Power Corporation. Times publisher Robina Gokongwei-Pe issued a front page apology and Estrada withdrew the complaint. But the issue forced the paper’s editors to resign. Estrada then trained his guns on the Philippine Daily Inquirer, with businessmen close to the president pulling their ad placements from the paper. The Palace press office also barred the Inquirer reporter from their media events for the paper’s biased reporting on Estrada. In the same year, the Manila Times was sold to Estrada’s political ally, former Manila congressman Mark Jimenez. The Times, Inquirer, and other media outlets extensively covered Estrada’s impeachment trial and eventual ouster on January 20, 2001.

Vice President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo assumed the presidency thereafter. She was initially perceived as media-friendly and accommodating chief executive. But the press had to do its job, especially at the height of the cheating scandal in the 2004 presidential elections. Media firms racked up stories about Arroyo’s controversial phone call to former Comelec commissioner Virgilio Garcilliano while the vote-counting was ongoing. The media later called this the “Hello, Garci?” tapes. Amid issues surrounding her legitimacy in office, Arroyo issued Presidential Proclamation 1017 which placed the country in a state of emergency on February 24, 2006. She also released media guidelines against the publication of “subversive” content. A day after, police raided the Daily Tribune, a renowned anti-Arroyo paper, confiscating copies of news reports and photos deemed as “destabilization materials.” The Supreme Court declared the seizure illegal and called it “plain censorship.” Under Arroyo, the single most deadly event for journalists happened in the infamous Maguindanao Massacre on November 23, 2009. Thirty-two newsmen and photojournalists were among the 58 victims of the mass killing after accompanying the relatives of gubernatorial candidate Esmael Mangudaddatu, who were about to file his certificate of candidacy against Datu Unsay mayor Andal Ampatuan, Jr. Their bodies were buried in a roadside in Ampatuan town using backhoes. To this day, the court has yet to render judgment on the multiple murder case filed against the Ampatuans and their accomplices. Arroyo’s successor Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III had a relatively easier time with the media, save for a few brickbats from some journalists who criticize his administration’s “student council” style of governance. Another factor was the hefty reputation of her sister Kris as the top multi-media talent of broadcast giant ABS-CBN.

All that changed when Rodrigo Duterte, the tough-talking mayor of Davao City, defeated a bevy of prominent political names in the 2016 presidential election.

1. lliberal democracy and the media

Fareed Zakaria put “illiberal democracy” on the global political map in a 1997 article which raised actually raised more questions than answers to its exact meaning. 4 He simply averred its definition to a rash of case studies opposite the form and/or substance of “liberal democracy.” The usual suspects lined up: Boris Yeltsin’s Russia, Carlo’s Menem’s Argentina, Alberto Fujimori’s Peru, Alexander Lukashenko’s Belarus, Abdala Bucarem’s Ecuador, Slobodan Milosevic’s Yugoslavia, and Ferdinand Marcos’ Philippines, among others. Zakaria may have missed a few more names on democracy’s “bad boys club” but there is no denying these leaders subverted and circumvented laws and institutions to shove personal interest ahead of their political mandate. This is not just plain rhetoric. Democratically elected regimes, often ones that have been reelected or reaffirmed through referenda, are routinely ignoring constitutional limits on their power and depriving their citizens of basic rights and freedoms (Zakaria, 1997).

Zakaria sees Western-style democracy 5 as liberal, predicated on an uncompromising regard for human rights and individual freedom. There is no quarrel with that. But liberal democracy as a condition of ordered rule is not just about parliamentary procedures hinged on free and fair elections, legislative channels, separation of powers, redress of grievances, and the rule of law. Its substance is as vital as its structure. The “basic liberties of speech, assembly, religion and property” under the tenets of what Zakaria called “constitutional liberalism” is a far longer row to hoe among transitioning or “hybrid regimes” and “flawed democracies” like the Philippines, based on The Economist Democracy Index in 2018. As Zakaria puts it 20 years ago, “Democracy does not necessarily bring about constitutional liberalism.” Dictators and a few straggling totalitarian regimes still persist, but increasingly they are anachronisms in a world of global markets, information, and media. There are no lone respectable alternatives to democracy; it is part of the fashionable attire of modernity. Thus the problem of governance in the 21st century will likely be problems within democracy (Zakaria, 1997, 42). But for John Street, the core tenet of liberal democracy is that since there is no uniformity of approach to how we live a good life, the definition of good life is therefore better left for the citizens to determine through voting and government should in turn respect the aggregate of choices made by the citizens through election. Liberal democracy does not require citizens to vote on all public issues as this is left for their representatives who are better equipped with skills and aptitude in the art of governance. Also, this spares the people the stress of elections on every public issue and business of running their political affairs (Street, 2001). Francis Fukuyama, who called liberal democracy as “the end of history” 6 (or the final form of government after the Cold War), admitted political myopia with the recent surge of duly-elected right-wing or populist posturing leaders across the world. “Twenty five years ago, I didn’t have a sense or a theory about how democracies can go backward,” he said in a phone interview with the Washington Post 7 in 2017.

If anything, Zakaria and Fukuyama were both right that Western-style democracy’s illiberalism lies in its proclivity for imperialism. The justifications for imperialism varied from nation to nation, from a crude belief in the legitimacy of force, particularly when applied to non-Europeans, to the White Man’s Burden and Europe’s Christianizing mission, to the desire to give people of color access to the culture of Rabelais and Moliere. But whatever the particular ideological basis, every “developed” country believed in the acceptability of higher civilizations ruling lower ones – including, incidentally, the United States with regard to the Philippines. This led to a drive for pure territorial aggrandizement in the latter half of the century and played no small role in causing the Great War. 8 Hyper-nationalism and war-mongering are likewise rife among democratic states not grounded on constitutional liberalism, Zakaria adds.

Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orban defined illiberal democracy further in a 2018 speech. He stressed that “Christian democracy” need not always espouse a liberal character, calling it “one trap – a single intellectual trap – which we must avoid.” Orban further submitted:

Let us confidently declare that Christian democracy is not liberal. Liberal democracy is liberal, while Christian democracy is, by definition, not liberal: it is, if you like, illiberal. And we can specifically say this in connection with a few important issues – say, three great issues. Liberal democracy is in favour of multiculturalism, while Christian democracy gives priority to Christian culture; this is an illiberal concept. Liberal democracy is pro-immigration, while Christian democracy is anti-immigration; this is again a genuinely illiberal concept. And liberal democracy sides with adaptable family models, while Christian democracy rests on the foundations of the Christian family model; once more, this is an illiberal concept. 9

Citing Orban as a case study, former Canadian politician and liberal party leader Michael Ignatieff couched illiberalism as “democracy vs. democracy” in an interview last April with the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs. The Hungarian prime minister would often assert that his election was democratically mandated by the people’s will whenever critics would brand his as “authoritarian.” Ignatieff agreed with Orban, but what the Hungarian leader only underscored was the procedural aspect of democracy which is chiefly hinged by elections as a political exercise . At the moment, Orban’s Hungary clearly lacked the “essence” of democracy anchored on upholding civil liberties, as Ignatieff observed:

He (Orban) uses democracy to crush democracy. He gets power and then he neutralizes the media.He neutralizes the courts, he locks up dissenters, he shuts off the universities. He’s been using democratic means to shut off democracy and that is the single most dangerous thing in the 21st century that is happening right now.If the press starts shutting down or if the press is unable to function freely that’s a bad sign that pretty soon democracy itself will be in danger. 10

Illiberalism can also be in good company with populism, buoyed by the election of a number of right-wing political leaders across the world. Populism, after all, is an outlook that emphatically claims to be democratic and that relies for its legitimacy on elections as expressions of the popular will. Yet when populists come to power, they tend to infringe upon the rule of law, the independence of the courts and the media, and the rights of individuals and minorities, as has been the case in Hungary. Moreover, these illiberal aspects of populism had begun to surface not just in countries lacking a liberal tradition but even in longstanding Western democracies (Plattner, 2019,10).

Warts and all, democracy remains a prerequisite to a free press. Liberal democracies, in particular, are expected to uphold press freedom as a civic right not only by journalists, but also by the audience they serve. Reports, editors, and TV anchors exercise this right to hold government and other stakeholders of public life accountable for their actions. In the grand scheme of things, truth and transparency become every well-meaning journalists’ rallying point. In the liberal theory of the press, private newspaper proprietorship prevents a state monopoly of the means of communication. Accurate and full information about politics is essential if polyarchic competition is to control politicians. Polyarchy is threatened when a ruling elite can control the flow of information about its action. Private owners want to make profit, so they provide newspapers which appeal to every section of the political spectrum, wherever they can accumulate readers (Dunleavy and O’Leary, 1987, 38). Yet the audience, where the once-silent majority used to retreat, does not see it that way lately. In fact, the messenger and receptor of good or bad news are not seeing eye-to-eye as they used to. There is an ongoing misunderstanding, perhaps a looming mistrust from the public with how media dispenses the truth nowadays through its multi-faceted paradigms of power. But just how liberal (or radical) can the media go?

From the traditional liberal pluralist standpoint, media is deemed to reflect rather than shape society. Media systems are open to a sufficiently wide range of voices, ideas, and opinions across society to legitimate public media’s role on behalf of society. This vision has its origins in the hard-fought liberal claim of freedom of expression. In order to serve society, the media must have a high degree of autonomy. Within a libertarian perspective, such autonomy is defined against “interference” by states whereas other liberal traditions incorporate role for the state as guarantor of communications against private interests (Hardy, 2010). Liberal functionalism, on the other hand, sees the media as a contributor to the “maintenance and reproduction of society.” To Hardy, both public and privately owned media in liberal societies carry out a wide variety of roles, cheer-leading the established order, alarming the citizens about flaws in that order, providing a civic forum for political debate, acting as a battleground among contesting elites. Media also convey messages from the people “below” to those in power “above” and thus have the role of “moral amplification” in systems of representative democracy (Hardy, 2010, 40).

The radical functionalist school of thought centers on the five filters of the Propaganda Model devised by Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky. It primarily calls out the elite domination of the media and the marginalization of dissent. It examines the dynamics of media operations in relation to its owners, reliance on advertising for profit, news sources such as government and other agents of power, negative responses to its reportage and conduct called “flak” and anti-communist (anti-Muslim, anti-Semitist, or racist) orientation as a political control mechanism. For Herman and Chomsky, the media’s unflattering ties with the powers-that-be compromises its watchdog role in the society. Leaders of the media claim that their news choices rest on unbiased professional and objective criteria… If, however, the powerful are able to fix the premises of discourse, to decide what the general populace is allowed to see, hear, and think about, and to “manage” public opinion by regular propaganda campaigns, the standard view of how the system works is seriously at odds with reality (Chomsky and Herman, 2008). Critics view the Propaganda Model as deterministic for limiting the media’s function to just reinforcing social inequality. It falls short of explaining the limitations set on the filters themselves. Media owners, advertisers, and government for one, cannot always throw their weight in the newsroom by commanding or dictating upon the “flow of news” without arousing suspicion and public backlash.

David Edwards and David Cromwell laid the groundwork for a more contemporary approach to radical functionalism, arguing that both the corporate mass media and the liberal media firms constitute a propaganda system for elite interest. This is built upon three major biases inherent in “neutral” professional journalism, such as reliance on official sources, news hooks, and carrot and stick pressures from advertisers. By news hooks, Edwards and Cromwell pertain to dramatic events, official announcement, or a publication of a report which justifies the coverage of a story, thereby favoring establishment interests and news management. The carrot and stick pressure meanwhile suggests businesses leading political parties herding corporate journalists away from social issues and towards others. Liberal revisionism, on the other hand, puts more emphasis on the autonomy of media professional to operate without undue political and economic stress from above. The radical pluralist approach meanwhile, bounds this autonomy to the structures of power regarded as “countervailing influences” such as state censorship, high entry costs, media concentration, mass market pressures, corporate ownership, advertising influence, consumer inequalities, rise of public relations, news routines and values, unequal sources, and dominant discourse. But for Nigerian scholar Ola Olateju, media freedom is anachronism in a liberal democracy. Its muted impracticality lies in the cornerstones of liberalism like competition, profit, and individualism which “compel the media to firstly be, a business venture and secondly, an instrument for the sustenance of the dominant social paradigm by the ruling elites” (Olateju, 2010).

Ramon Tuazon, former president of the Philippine Association of Communication Educators Foundation and associate director of the Asian Institute of Journalism and Communication, echoes Wolf’s correlation between wealth bolstered by liberal economic policies and media ownership, which is also evident in the Philippines. Free enterprise allows extensive access to resources for newsroom development in terms of technology and personnel. To further boost its capital outlays, big media players enlist in the stock market. For Tuazon, this policy of “let the marketplace determine the kind of media” or “let the media sort itself out” which amounts to a hands-off policy has perhaps been the single factor that has contributed to the elite orientation of media, the control of media by those who have economic and political power, and the predominance of entertainment and trivia. Data from Reporters Without Borders and Vera Files support this observation, branding as “high risk” the ownership concentration of multi-media outfits in the hands of a few people under a conglomerate set-up. The ownership concentration indicator was measured by adding up the market shares of the top media companies, notably broadcast giants ABS-CBN, GMA, and TV 5. It found out the following: “ABS-CBN Corporation and GMA Network Incorporated are without a doubt the front runners of the media market. They together gather a market share of 79.44 percent. The top 8 companies operating cross-media (which means in at least two media sectors) get almost all of the cake (96.46 percent). Even if advertising budgets was not available for all media, the trend shows that the Big Two also benefit from selling advertising space, with most money coming from TV (Nielsen, Ad Spending). Business tycoon Manuel V. Pangilinan is involved in all media sectors through his MediaQuest Holdings Incorporated that holds TV5 Network Incorporated (TV, radio, online), Nation Broadcasting Corporation (radio, TV) and Hastings Holdings (print). However, based on 2014 data, Pangilinan’s media companies are unable to keep pace with the major players financially. TV5 Network Incorporated is operating at a loss ($-82.43 million). His telecommunication companies however balance the loss as PLDT and Smart Communications have revenues of $3652 million, and a profit of around $569 million.” 11

2. Duterte’s ‘trimmed” co-optation toolbox

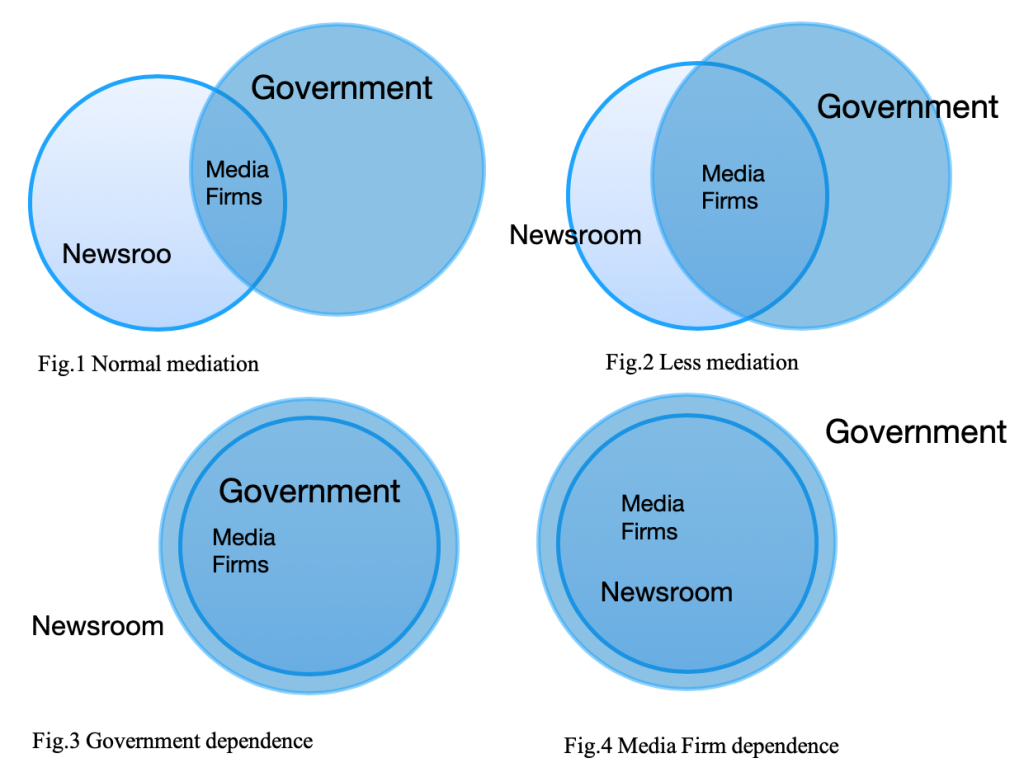

This study drew a more compact or “trimmed” version of the Freedom House Media Co-optation Toolkit to better explain Duterte’s combative demeanor toward certain media organizations, notably online news portal Rappler, print leader Philippine Daily Inquirer, and broadcast giant ABS-CBN. This will also explain how Duterte has kept the Philippine media “at bay” without deliberately breaking media laws protected by the constitutional rights of free expression, speech, and of the press. The Freedom House Media Co-optation Toolkit (Box 1) to “achieving media dominance” is divided into two segments aimed at “squelching critical outl ets” and “bolstering loyal outlets.” Each segment is subdivided into “tools” — economic, legal and extra-legal with contrasting indicators aimed at punishing the regime’s enemies among media outlets on the one hand, and rewarding its supporters on the other.

But for this study, the researcher focused on “squelching critical outlets” using a “trimmed” matrix of indicators to cover the case studies (Box 2). The “selective enforcement of laws” cannot be applied to Duterte since there are no clear-cut cases where the president set aside legal actions against other media organizations that have supposedly violated the law in the same manner with how he has viewed the Inquirer, Rappler, and ABS-CBN. The president may prefer other media companies like the Manila Times or the Philippine Star but the charge of selectivity or prejudice in favor of these outlets has yet to be unarguably proven at the moment. The “abuse of regulatory and licensing practices” is likewise inapplicable to the administration since it has yet to actually veto legislation on the franchise renewal of ABS-CBN on personal or whimsical grounds. The indicator on “permitting impunity for threats against journalists” is integrated with the “smears by proxies’ through troll farms or social media supporters which Duterte later admitted after winning the elections.

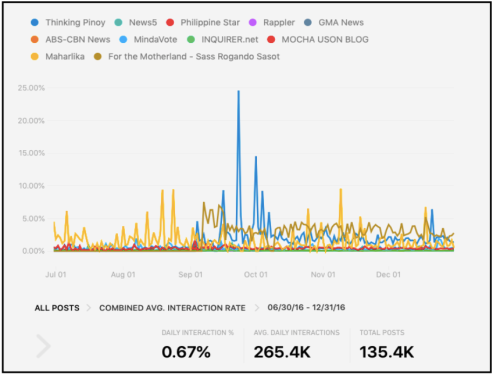

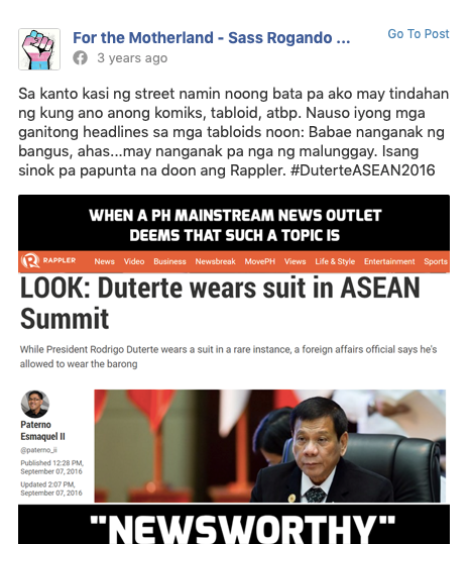

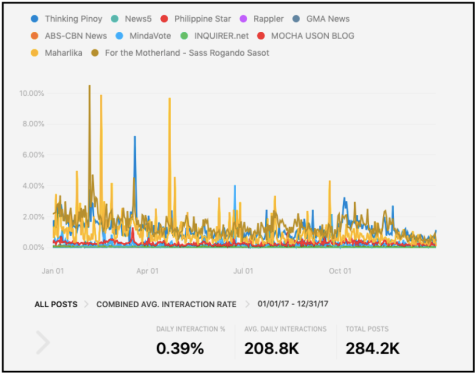

To prove how Duterte actually employed the toolbox model, this study cited cases involving the administration’s perceived mainstream media adversaries, notably online news portal Rappler, print leader Philippine Daily Inquirer, and broadcast giant ABS-CBN. Duterte’s success in capturing the news narrative from the mainstream media was remotely gauged through the consistently high interaction rate generated by pro-administration personalities in social media. Most of these interactions (comments and reactions) were noticeably in favor, or in defense, of the administration. The interaction rate and other pertinent data was accessed using the content discovery and social monitoring platform Crowdtangle. The main case studies were the following: for Rappler, the arrest of its president and CEO Maria Ressa on February 15, 2019; for the Inquirer on its sale to Duterte ally Ramon Ang on July 17, 2017; and for ABS-CBN on the issue of its franchise renewal which Duterte vowed to block, owing to the network’s failure to air his TV ads back in the 2016 elections.

3. The toolbox ‘repairs’ the media

The distortion of parliamentary democracy by big media corporations is often seen through the prism of media barons. Analysts and critics picture them as proto-monarchs in the age of democracy, information bosses who enjoy “power without responsibility” to the point where their media propaganda and string-pulling make them influential political players capable of making and unmaking government (Munhamn, 2010). Media bosses are political kingmakers. Like other businessmen trained in the grammar and philosophy of rent-seeking, they invest on political relationships with the powers-that-be by financing their campaigns or projects. Big media firms are not much interested in governmental power for mischievous personal ends. Their chief concern is to secure existing investments and to consolidate their flanks by winning bigger and better deals. That is why, if they consider it to be in their interest, they will deal with any government and enter willingly into its arrangements, even when they fall far short of the standards of monitorydemocracy (Keane, 2013). Duterte knew this from the get-go, despite being a rookie in national politics in 2016. The media for one created and propagated his “Dirty Harry” image as Davao City mayor. He was good material for journalists to pick with his crackling sound bites and simple-man attitude. But provincial Duterte was in no mood to humor Imperial Manila’s media bosses, who are directly or indirectly connected or collaborating with his political enemies and election adversaries. This can be gleaned from the media co-optation toolkit, as well as the economic/legal and extra-legal measures, he employed against ABS-CBN, Inquirer and Rapper when he assumed the presidency.

A. Government-backed ownership takeover

Born after the 1986 EDSA People Power, the Inquirer slowly earned its reputation as a crusading paper, criticizing government over certain excesses or wrongdoings. It does not balk against public officials who commit abuse of power or authority, in the same way that most of its senior editors and writers battled Marcos and his mail-fisted tactics during the Martial Law years. Duterte as a self-confessed Marcos admirer was a given target, from his defense of the infamous “War on Drugs” to issues on the West Philippine Sea, and his political alliance with the Marcoses, the Inquirer always has a story or two, giving the other side of the picture. The drug war, more popularly known as “Oplan Tokhang” 12 continues to be hounded by alleged extra-judicial killings (EJK); the West Philippine Sea had Duterte’s affinity with China as an issue, and the Marcoses for reviving, their political careers.

The Inquirer mounted a running tally of drug war victims on the first few months of Duterte’s bloody anti-narcotics campaign. But Inquirer associate editor John Nery clarified the tally, which was already removed from the publication’s website, was not a “kill list.” It was a “listing of the names and other particulars of people killed” in the drug war. 13 From July to September 2016, the Inquirer recorded 1,027 drug-related deaths, including 273 unidentified persons. The Philippine National Police (PNP) said some of the drug suspects were classified as “nanlaban” or were killed after engaging the arresting or pursuing officers in a gun-fight.

“It’s very difficult to see the difference between a thousand deaths and two thousand deaths and it becomes just a mere statistic. So, the idea for the kill list was to identify as much as possible the people who are killed in both police operations and vigilante-style operations,” Nery said in a Senate probe back in 2016.

Since Duterte assumed power in 2016, the Inquirer published at least 36 editorial related to the war on drugs and its relation to extra-judicial killings, which would later include the deaths of minors such as Kian Delos Santos, Carl Angelo Arnaiz, and Reynaldo “Kulot” De Guzman, among others. Most of these were critical pieces on Duterte’s centerpiece anti-crime program. One editorial 14 recalled how “Oplan Tokhang” was used by rogue cops to kidnap and kill Korean businessman Jee Ick-joo inside the main police headquarters in Camp Crame on October 2017. Oplan Tokhang was then suspended and anti-drug units under the PNP were disbanded. The Inquirer blasted former PNP chief Ronald “Bato” Dela Rosa for calling as “police whims” the wave of unexplained killings done by the police force in the first and second phase of the “tokhang” operations, which Duterte described as “collateral damage,” to wit:

“Police whims” is a strange explanation for the violent conduct of the first stages of Oplan Tokhang. Dela Rosa himself testified in the Senate that thousands of drug personalities had been killed in police operations (Kipo), while thousands more were killed in mysterious or unknown circumstances (the label the police use is DUI, for deaths under investigation). He justified police action that led to the Kipo as done under threat, because the suspects fought back. (“Nanlaban,” the Filipino term for that, which the police themselves use in describing the reported encounters, has also become an all-too-familiar word.)So if the suspects fought back, in the majority of Kipo cases, what police whims is he talking about?

The case of 17-year-old Kian delos Santos, who was recorded on camera being dragged by plainclothes policemen to what turned out to be his place of execution, shook the country because it offered incontrovertible proof of police cruelty.

And yet the police have defended the actions of their men who grabbed Kian, even describing the young student as a drug runner. Is this determined circling of the wagons a police whim?

The truth is: The PNP has not come clean about its dirty policies and its dirty cops. No less than the President thundered that as much as 40 percent of the police was corrupt, or in the control of drug lords and operators.

What has the PNP done since the President said that a year ago to bring these corrupt cops to justice, to root out the causes that lead to corruption within, to discipline the rest of the force?

Unless this rot is cured, the “true spirit” of tokhang may grow strong again, but the “flesh” of the PNP will remain weak. (Inquirer, January 2018)

Another editorial 15 stressed the extra-judicial killing angle by parsing through a Social Weather Station (SWS) survey which showed 68 percent of Filipinos saying the police are involved in the illegal drug trade and 66 percent believing they orchestrated the EJKs of alleged drug suspects despite repeated government denial of any state-sponsored killings under the pretext of the war on drugs. The most striking statistic was 78 percent of 1,400 surveyed adults fear they could be victims of EJK, a five-percent increase from the June 2017 figure of 73 percent. The Inquirer also took Duterte to task for claiming the number of drug users in the country reached 7 to 8 million, way further than the 1.8 million figure of the Dangerous Drugs Board in 2016 and twice the president’s 3 to 4 million estimate. PNP chief Oscar Albayalde admitted he was not privy to the president’s drug-war data which may have come, he said, from “unlimited sources.” It said:

In other words, the President was making up numbers, in a bid to intensify his war. After declaring, on Feb. 20, that the campaign will be “harsher in the days to come,” he was asked if that meant a “bloodier” war. “I think so,” Mr. Duterte replied. He was the President, he said, and “I will not allow my country to be destroyed by drugs. I don’t want my country to end up as a failed state… it behooves upon me to see to it that my country is safe.”

But how safe is a country that has seen tens of thousands of deaths of its own citizens, and millions more in the grip of anxiety that they would suffer the same bloody fate, not in the hands of criminals, but in the hands of the police themselves?

As (SWS president Mahar) Mangahas pointed out, “The collateral damage of the deadly war on illegal drugs includes the people’s loss of trust in the police.” (Inquirer, March 2019)

But a few days after the “war on drugs” commenced upon his orders, Duterte hit the Inquirer in his first State of the Nation Address (SONA) for publishing the photo of a dead drug suspect depicting Michaelangelo’s famous “Pieta” which originally portrayed a grieving Mary holding the body of Jesus Christ. The photo, taken by award-winning lensman Raffy Lerman, riled the president for putting the PNP in a bad light, although the Inquirer did not say the police actually gunned down the “Pieta” suspect named Michael Siaron.

“Eh, tapos nandiyan ka nakabulagta and you are portrayed in a broadsheet na parang Mother Mary cradling the dead cadaver of Jesus. Eh ‘yan yang mga ‘yan magda-dramayan tayo dito,” 16 Duterte said, a day after the photo was published.

A year later, Malacañang officials would claim that Sairon was killed by drug syndicates. Former Presidential Spokesman Ernesto Abella defended the PNP, which took the blame for the killing: “The relentless attribution of such killings to police operations was both premature and unfair to law abiding enforcement officers who risk life and limb to stop the proliferation of illegal drugs in our society.” 17 The Inquirer would take further tirades from the president and his allies, branding the paper as a peddler of lies or “fake news” against the government.

On July 17 of the same year, the Inquirer owners surprised the Philippine media industry by announcing the sale of their majority stocks to billionaire Ramon Ang of the San Miguel group. It was no secret that Ang was a Duterte supporter and the president liked him. But the Prieto family which owned 85 percent of the Inquirer group for 25 years said it was a “strategic business decision” to “maximize growth opportunities” amid talks that the paper’s management wilted under government pressure. Ang, who has been in talks with the Prietos for the acquisition deal since 2014, assured the paper he would “continue to uphold the highest journalistic standards and make a difference in the society it serves,” denying accusations that he was a Trojan Horse sent by the administration to turn the Inquirer into a Duterte mouthpiece.

Inquirer employees were both shocked and saddened by the turn of events. Some couldn’t help but worry that Ang’s entry into the company may compromise its editorial independence, given the power play that entailed the acquisition deal. One employee said: “We had a number of meetings where we were told to be brave, to soldier on. Never did we think we’d be sold off to a Duterte campaign donor at that. Just imagine our disbelief.” 18 Malacanang distanced itself from Ang’s venture. But Inquirer employees, composed of some of the most grizzled newsmen in the country, knew the political concession with one of Duterte’s top supporters was already settled beyond the public eye. The power of elites always thrives on secrecy, silence, and invisibility (Keane, 2013, 41). Keane calls this “mediacracy” which “delves critically into a hidden world not normally covered by journalists, or spoken about by politicians or seen naked with public eyes. It is a new form of political oligarchy, top-down power that is heavily unedited, especially through the press, radio, television, a new method of governing through invisible webs of backchannel contacts and closed information circuits (Keane, 2013, 174). But media bosses only step into the newsroom when their business interests are compromised.

Take the case of Manny V. Pangilinan, who has stakes in power and water utilities, mining, logistics, and telco industries. But MVP (as he is known in business circles) also has controlling stakes in Cignal TV, TV 5, the Philippine Star, and Business World, aside from owning 15 percent of the Inquirer. He and his top executive do not meddle on media operations during “neutral” news days or when there are no stories or issues that could directly or indirectly distort their corporate reputation. Yet when controversies drag his business interests into the mud, Pangilinan makes sure his company’s rejoinder or demurrer will be heard but not without going through the proper vetting of his media managers, just like any other reaction stories. However, the angle or slant to give the media boss a more favorable coverage is another matter. 19

Vergel Santos, a veteran editor, journalist, and CMFR board member, partly subscribes to this observation by recalling a conversation he had with ABS-CBN owner Geny Lopez when they re-opened the family-owned Manila Chronicle after Marcos was deposed: The older Lopez told him: “Run the paper as you like. I will not get in the way,’ he told me. “All I ask is that if you have bad news about me or my family or our businesses, print our side in it.’ In other words, he asked for no more than any other news subject deserves and each time his word was tested it proved good.” 20

Ang previously sought to acquire the majority shares of the Guzom family in GMA 7 but talks collapsed in 2015. He was also rumored to have a stake in Nine Media, which carries the CNN Philippines brand. But unlike Pangilinan or the Lopezes, Ang’s takeover of a perceived Duterte enemy speaks volumes, given his actual or apparent closeness to some Palace officials, and the president himself. The amiability between Duterte and Ang was underscored by the president’s own admission back in December 2016 that his new-found billionaire friend pitched in “not a lot, but not too little” in his campaign. Ang however was not included in the president’s Statement of Campaign Expenditures (SOCE). San Miguel Corporation, which Ang manages as president and chief operating officer, also helped in the Duterte administration’s anti-drug campaign by donating P1 billion for the construction of drug rehabilitation facilities. Short of expressing gratitude, the Duterte administration awarded a number of government infrastructure project to San Miguel Corporation, where Ang is president and chief operating officer. One of these was the $15 billion Bulacan international airport which had San Miguel winning the Swiss challenge 21 of the Department of Transportation as the only qualified bidder and developer. Ang is also proposing to build an elevated ramp along EDSA with dedicated lanes for the government’s bus rapid transit system. The project costs P3 billion but Ang said he is willing to foot the bill to help the government address Metro Manila’s traffic woes. With the foregoing, it is viewed that Ang as owner may exercise internal or self censorship to keep the paper’s hostility towards the government in check and stay in the good graces of the administration. This however remains to be seen, as the transfer of ownership is yet to be finalized with the Philippine Competition Commission (PCC), which is mandated by law to review acquisitions and mergers valued over P1 billion. 22 Ang however refused to disclose the amount of the brokered deal with the Prietos. In essence, Duterte’s political sleight of hand, is well evident in the Ang takeover. For one, there is no evidence that Malacanang actually ordered the Inquirer acquisition with Ang as intercessor, but the political affinity between Duterte and Ang is undeniable. And to keep the political capital which the president’s friendship accorded him, Ang is expected to pacify the Inquirer. Yet that won’t be easy, given the bridge of “anti-Marcos, anti-government abuse” sentiment linking the opposition and majority of the Inquirer’s leaders since 1986. It becomes more telling against a president, who openly admires the old Marcos and subscribes to Marcosian tactics like alleged summary executions, various human rights violations, martial law declaration (in Mindanao), and media suppression, among others. That Ang is a former righthand man of a known Marcos crony like Danding Cojuangco is enough fodder to burn the political roast on the Duterte government’s unholy alliance with the enablers and gainers of the Martial Law years. Curiously enough, this narrative is now being protected by the shield of public opinion in favor of the president.

B. Arbitrary tax investigations/ other cases

Rappler stands in the middle of a unique and vexing ownership issue. According to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the online news portal violated the Constitution, the Anti-Dummy Law and other related corporate codes by belatedly registering as “donation” the Philippine Depository Receipts (PDR) it issued to Omidyar Network sans the SEC’s approval. This suggestively gave the foreign entity owned by American billionaire entrepreneur and eBay founder Pierre Omidyar to have a controlling stake in a media company which ought to be 100 percent Filipino-owned. Article XVI, Section 11 of the 1987 Constitution provides: “The ownership and management of mass media shall be limited to citizens of the Philippines, or to corporations, cooperatives or associations, wholly-owned and managed by such citizens.” The insurer Rappler Holdings Corporation admitted owning 98.84 percent of Rappler. But the SEC ruled revoke Rappler’s certificate of incorporation:

Rappler stands in the middle of a unique and vexing ownership issue. According to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the online news portal violated the Constitution, the Anti-Dummy Law and other related corporate codes by belatedly registering as “donation” the Philippine Depository Receipts (PDR) it issued to Omidyar Network sans the SEC’s approval. This suggestively gave the foreign entity owned by American billionaire entrepreneur and eBay founder Pierre Omidyar to have a controlling stake in a media company which ought to be 100 percent Filipino-owned. Article XVI, Section 11 of the 1987 Constitution provides: “The ownership and management of mass media shall be limited to citizens of the Philippines, or to corporations, cooperatives or associations, wholly-owned and managed by such citizens.” The insurer Rappler Holdings Corporation admitted owning 98.84 percent of Rappler. But the SEC ruled revoke Rappler’s certificate of incorporation:

The Foreign Equity Restriction is very clear. Anything less than One Hundred Percent (100%) Filipino control is a violation. Conversely, anything more than Zero percent (0%) foreign control is a violation.It does not matter what capacity or device gives the foreigner control, as stockholder or holder or otherwise, there must be none. It does not matter if control is only available in certain occasions, there must be no occasion. 23

Omidyar Network described the SEC decision as an “unfortunate interpretation of Filipino law that reduces press freedom and independent news coverage in the Philippines.” It argued that PDRs do not provide the holder any ownership of shares in the underlying entities,” while stressing the SEC did not flag the PDRs when it was first issued in 2015. Omidyar also insisted Rappler did not violate the Constitution:

In accordance with the Constitution and laws of the Philippines, Omidyar Network does not own any shares in either Rappler Holdings Corporation or Rappler Inc., nor does it have any voting rights, management responsibilities or any other form of control in either company, nor any editorial input in Rappler.Rappler Inc., which operates an independent, social news network, is wholly owned and controlled by Filipino citizens and entities that are wholly owned and controlled by Filipino citizens. 24

The Court of Appeals upheld the SEC position that Rappler erred by belatedly registering the PDR donations made by Omidyar Network and another foreign investor, North Base Media. But it held the view that the revocation was too much, and putting the media firm out of business should have been the “last resort” since the SEC procedures, based on law, allows corporations “reasonable time” to correct acts of non-compliance. The appellate court also stressed that the PDR donations made by foreign investors to Rappler did not affect its standing as a Filipino-owned enterprise as the “negative foreign control” clause which supposedly gives Omidyar and North Base “voting power” over company policies and issues was never exercised at all before the PDR donation was made. In a media forum in London, Ressa dismissed claims that she was an Omidyar lackey but admitted to receiving a multi-million dollar investment from the global media mogul. “Let’s take a look at the full range of investments. There’s a (inaudible) of about four and a half million dollars that went into Rappler. Only four and a half million dollars. Only. And we’ve been able, that seven years of doing hard hitting investigative reporting … Of that, probably less than five percent came from Omidyar,” 25 she said.

Compounding Rappler’s legal troubles were four tax-related suits which the government slapped on the online media platform, in relation to the Omidyar PDRs, which the Bureau of Internal Revenue believed had generated taxable income that Rappler Holdings Corporation failed to declare. Three of these charges were lodged before the Court of Tax Appeals (CTA). Rappler president and CEO Maria Ressa pleaded not guilty on the charges: one count of tax evasion and three counts of alleged violation of Section 255 of the Tax Code or failure to supply correct information in the Income Tax Return (ITR) for 2015, and Value Added Tax (VAT) returns for the third and fourth quarters of 2015. 26

Rappler also faces a fifth tax case at the Pasig Regional Trial Court (RTC) for not declaring P294,258.58 of taxable income in the second quarter of 2015. But since the amount involved was below the P1 million minimum requirement for cases at the CTA, the justice department filed the case at the Pasig RTC Branch 265. Ressa posted a P60,000 bail on December 3, 2018 to avoid arrest.

The online media platform was also charged for violating the Anti-Dummy Law and the Securities Code as an off-shoot of the PDRs gaffe which allegedly involved foreign entities in the Rappler management. Six of the seven Rappler board members posted a P216,000 bail each. Four of them were arraigned and pleaded not guilty before the Pasig RTC Branch 265 on April 10 this year. The case was later transferred to Branch 159 after Judge Rowena San Pedro inhibited, citing her friendship with Ressa.

Ressa was later arrested on February this year, following a cyber libel complaint filed by businessman Wilfredo Keng from a story that implicated him to the late Chief Justice Renato Corona, who was facing impeachment at the time. The arrest was live-streamed by Rappler. The story, published in May 2012, claimed Corona used a vehicle owned by Keng, who had alleged links with illegal drugs and human trafficking syndicates. Keng reportedly requested Rappler to take down the malicious story against him, but the media firm refused to and did just minor revisions on February 2014. Keng charged Ressa and former researcher Reynaldo Santos, Jr. on October 2017 but the National Bureau of Investigation dismissed the complaint on February 2018, saying the one-year prescription period for libel had lapsed in 2013. But the justice department reviewed the complaint after finding out the article can still be accessed on the internet and is now covered by the Anti-Cybercrime Law enacted on September 2012.Insisting the law cannot be applied retroactively, Rappler filed a motion to quash, which the court junked. Ressa and Santos were arraigned on May 14 this year.

But Rappler is not alone in the government’s legal leash. The Inquirer is also embroiled in several court battles, notably the Mile Long case involving the government and the paper’s owners since 2009. Duterte pounced on this issue, accusing the Prieto and Rufino families’ Sunvar Realty Development Corporation of cheating the government for the non-payment of taxes amounting to P1.8 billion. On the same day the Inquirer sale to Ang was announced, the president threatened to turn the 6.2-hectare Mile Long property to socialized housing units. “I will recover the property for the Filipinos. Everybody who has a tax obligation must start to talk now. Within six months time, I will go after them. I will get back. Inquirer, you have to let go of that property. It is not yours,” the president said in a news conference on April 27, 2017.

“‘Yung mga crusaders na mga newspaper, bakit sila corrupt rin? Answer me. That Mile Long. Who owns it? Rufino. Who is Rufino? He is married to Prieto… I assure you, after all of these things here, I will start to recover what is government’s property, including that Inquirer. The loudest, one of the loudest of it all. Crusader kuno, ‘yun pala crony rin.” 27The Manila Times said the president’s pronouncements came a few days after one of its columnists, former ambassador and press secretary Rigoberto Tiglao wrote about Mile Long’s unpaid obligations. 28 He also claimed that the Prietos also owed the government P.15 billion in taxes for the other company it owned, Dunkin Donuts. All told, he said the unpaid taxes would amount to “nearly P3 billion, putting them in the league of Chinese-Filipino tycoons notorious for being tax evaders.” Tiglao, a known Duterte supporter, also exclaimed: “No wonder President Duterte himself angrily said in a recent speech that he will investigate the case, which was reported to him as having been a ‘sweetheart deal’ when it was leased by a state firm to the Rufino/Prietos’ firm Sunvar Realty Development Corp.” Duterte followed up that stern warning with a harsher remark in July: “These newspaper owners, who do they think they are? The way they editorialize people in government saying they are thieves. You have hostaged a government property for so long a time and collected the rentals there. That is swindling,” the president said.

On July 19, the Court of Appeals affirmed its January decision junking the Makati RTC Branch 59’s injunction against the evection order on the Mile Long tenants for the lack of jurisdiction on the case. The appellate court also remanded the proceedings to Branch 141 which originally heard the case. Nine days later, Solicitor General Jose Calida demanded Sunvar to vacate the property while hitting the Prietos for using the Inquirer to “shield your shenanigans.” The president’s took the cudgels anew in an August 2 event, telling the Prietos that the will sue them for “economic sabotage” if the family continues to occupy the Mile Long property with its 273 tenants. On August 15, Calida personally served the Notice to Vacate to the Mile Long tenants, alongside the CA resolution authorizing the Makati RTC Branch 141 to implement the vacate order. The following day, Sunvar vacated the property with the Prietos, sans fireworks from the Inquirer, staying silent on the matter.

The government pinned the Prietos anew in 2018 after the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) filed a P1-billion tax evasion complaint before the Department of Justice against the family-owned Golden Donuts, Incorporated (GDI), the local franchisee of Dunkin Donuts. The BIR discovered that GDI have an outstanding tax deficiency amounting to P1,118,331,640.79 while under-declaring sales by 36 percent back in 2007. A Business World report summarized GDI’s tax deficiencies as followed: P840.82 million in income tax, P270.42 million in value added tax (VAT) and P7 million in expanded withholding tax (EWT). 29 GDI denied the charge, saying it has already settled its tax liability in 2012. Paolo Prieto, the president of Inquirer.net was recently charged with tax evasion, along with GMA Network Inc. chairman and CEO Felipe Gozun over INQ7, a former joint venture of the two companies in the early 2000s. The BIR said the venture failed to pay the corresponding tax liability of P23,479,467.13, inclusive of increments or penalties, in 2006, the same year it was disbanded.

ABS-CBN was practically in the same boat, but it did not wait for Duterte to unleash more vitriol on the broadcast giant, opting to settle its P152.44 million tax deficiency in 2009, as part of a compromise agreement with the BIR. The Court of Tax Appeals (CTA) approved the stipulations in a February 27 resolution this year, saying the BIR has “accepted the amount equivalent to 40 percent of the basic tax assessed for deficiency income tax, value-added tax and documentary stamp tax and the amount equivalent to 100 percent of the basic tax assessed for deficiency expanded withholding tax, compensation withholding tax, and final withholding tax.” 30 The network entered into another compromise deal with the BIR in August to patch up the P30.952 million tax liability of its subsidiary company ABS-CBN Film Productions, Inc. The (CTA) approved the compromise which allowed ABS-CBN to pay only P16.105 million from the original amount the BIR previously charged to the network.

ABS-CBN was practically in the same boat, but it did not wait for Duterte to unleash more vitriol on the broadcast giant, opting to settle its P152.44 million tax deficiency in 2009, as part of a compromise agreement with the BIR. The Court of Tax Appeals (CTA) approved the stipulations in a February 27 resolution this year, saying the BIR has “accepted the amount equivalent to 40 percent of the basic tax assessed for deficiency income tax, value-added tax and documentary stamp tax and the amount equivalent to 100 percent of the basic tax assessed for deficiency expanded withholding tax, compensation withholding tax, and final withholding tax.” 30 The network entered into another compromise deal with the BIR in August to patch up the P30.952 million tax liability of its subsidiary company ABS-CBN Film Productions, Inc. The (CTA) approved the compromise which allowed ABS-CBN to pay only P16.105 million from the original amount the BIR previously charged to the network.

Media firms at the receiving end of these legal suits would naturally hit back and question the motive of the government. But the Duterte administration can either ignore the political noise or invoke its role as agents of the public good, mandated to go after individuals or entities which commit major infractions against the state and its laws. What is political blackmail for media hardliners is simply political will for the government. These cases become more potent, not in the legal docket, but in the court of public opinion as it primarily targets the media’s credibility. It cannot be denied that a media company’s main political capital is its credibility, which translates to trust (or the lack of it) as determined or framed by its audience. An eroded credibility is vulnerable to charges of hypocrisy. Just like what he did to the opposition, Duterte had successfully painted Rappler, Inquirer, and ABS-CBN as hypocritical organizations which have long deceived the public by projecting themselves as purveyors of truth and justice, but were actually no different from the crooks and corruptors in government, basing on their cases of tax evasion and other similar issues. To stop the government’s credibility attacks, media firms are forced either to kow-tow or conform to the words, whims and wishes of the sitting power. But that cannot be said of Rappler, which continues to engage the government, both in the court of law and that of public opinion.

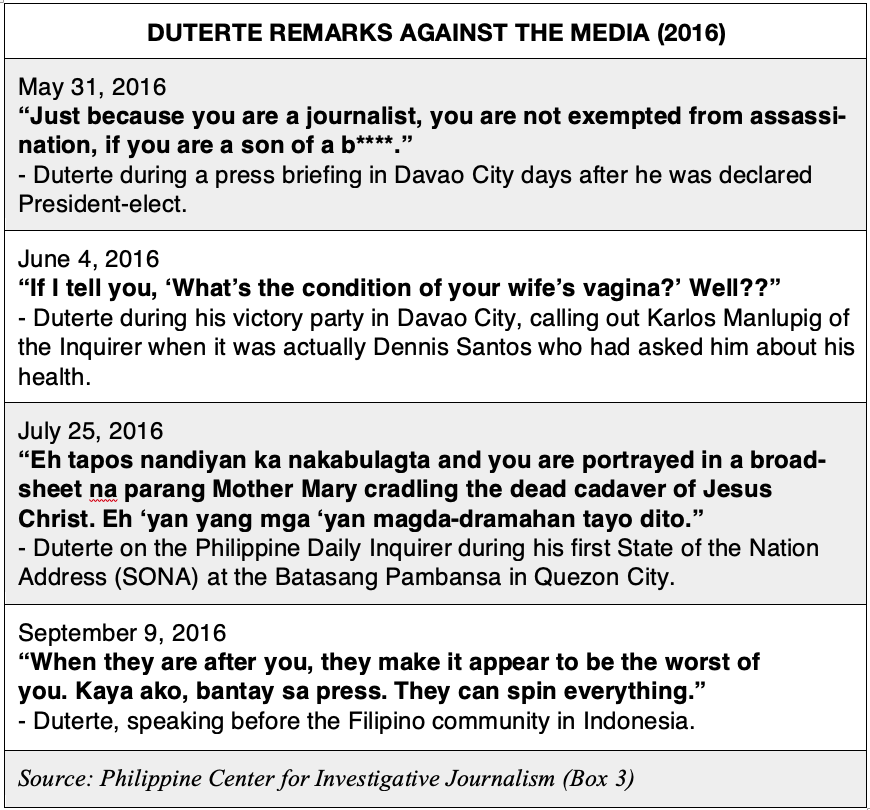

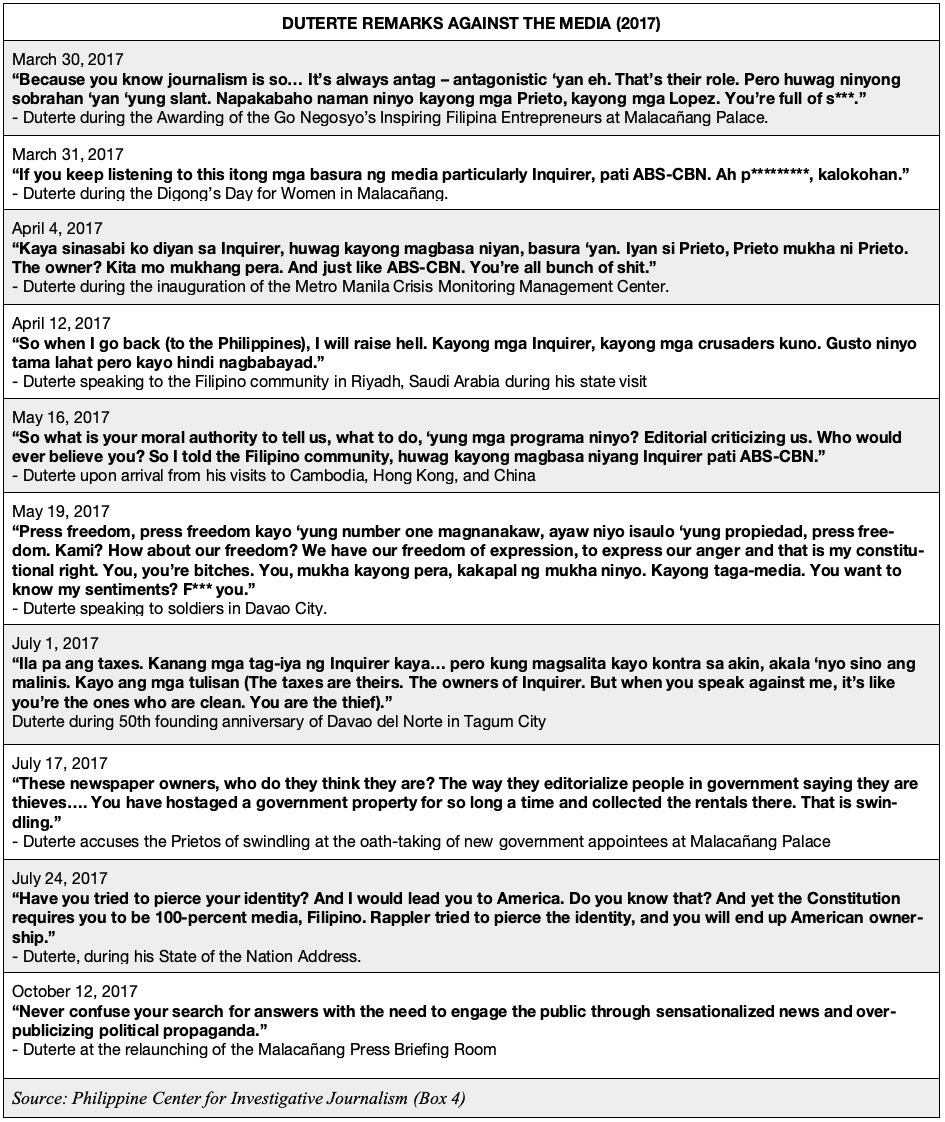

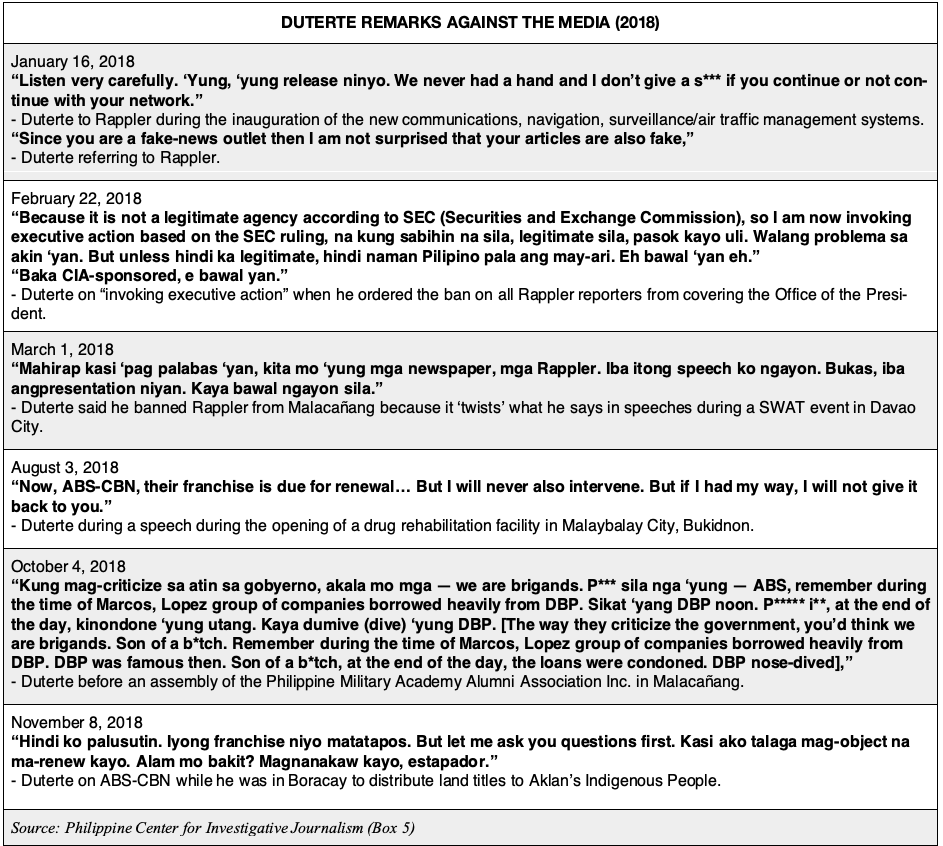

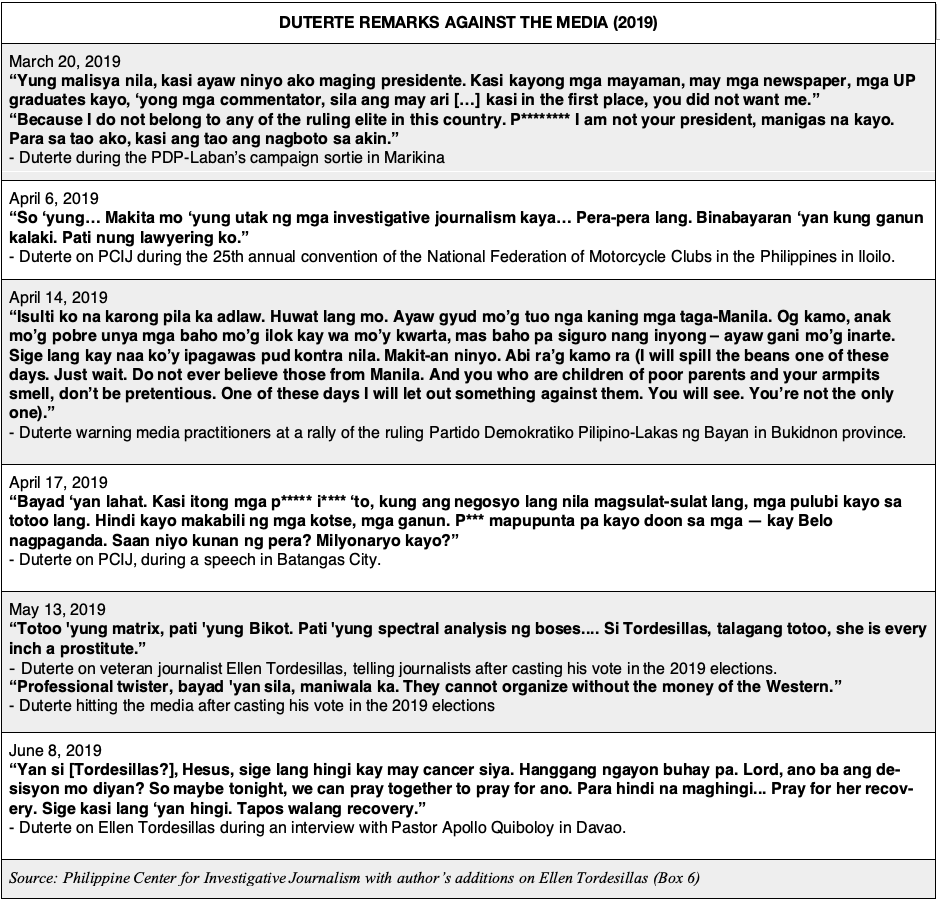

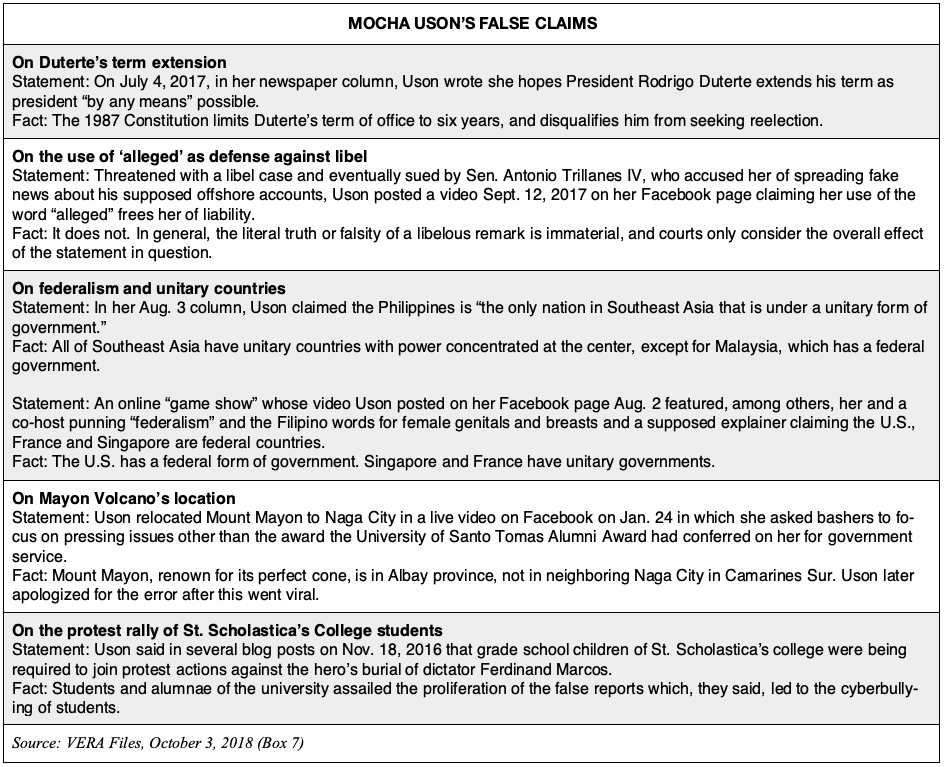

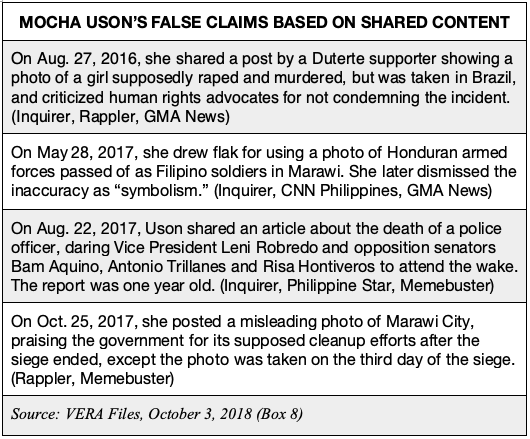

C. Verbal harassment

Among media platforms, TV is still the most influential despite the migration of more news content to the internet. In the Philippines, broadcast giant ABS-CBN continues to dominate the ratings, and had since carved a niche as a major political player, especially during elections. Politicians spend millions of pesos to buy airtime for a 30-second ad. The rate card can go higher when ads are placed between prime time programs.

ABS-CBN reportedly charges its political clients P900,000 for a 30-second ad in non-primetime shows and P1.4 million for primetime shows. It is still unclear how much Duterte actually spent on TV ads alone. The Inquirer, ABS-CBN’s print counterpart in terms of reach and clout, also made millions from political ads in the 2016 election. Based on its October 2016 rate card, a full page black and white ad costs P183,600 and P330,480 for colored ads placed from Monday to Saturday. The ad placement amount is more expensive on Sundays (P211,140 for black and white, and P380,052 for colored). Data from the PCIJ showed that Duterte spent a total of P146,351,131 for political ads, and appeared in 1,533 of these spots alone, before the 2016 elections. 31 This ads issue was Duterte’s beef with ABS-CBN. He claimed the broadcast giant did not air his TV ads worth P2.8 million but showed black propaganda materials paid by his political enemy, senator Antonio Trillanese. The P2.8 million he paid was only added to his net worth months after he assumed office.

From hereon, Duterte would lash-out at at ABS-CBN for giving him the short end of the bargain. He would curse the Lopez family, accuse them of political double-dealing and various legal transgressions. Duterte had also repeatedly called out the network for allegedly dishing out biased and defamatory reports or commentaries against his administration. But the president’s most serious threat to the Lopez crown jewel was the non-renewal of its franchise, which is set to expire in 2020. Backstopped by a supermajority in both Houses of Congress. Duterte can practically end ABS-CBN’s 65-year corporate existence. Media firms are run like public utilities, which require franchise renewals from Congress, and ultimately presidential approval. This practically puts media companies at the mercy of politicians, who can implicitly or explicitly ask favors like quelling negative news or publicity against them, and propping up their image, among others.