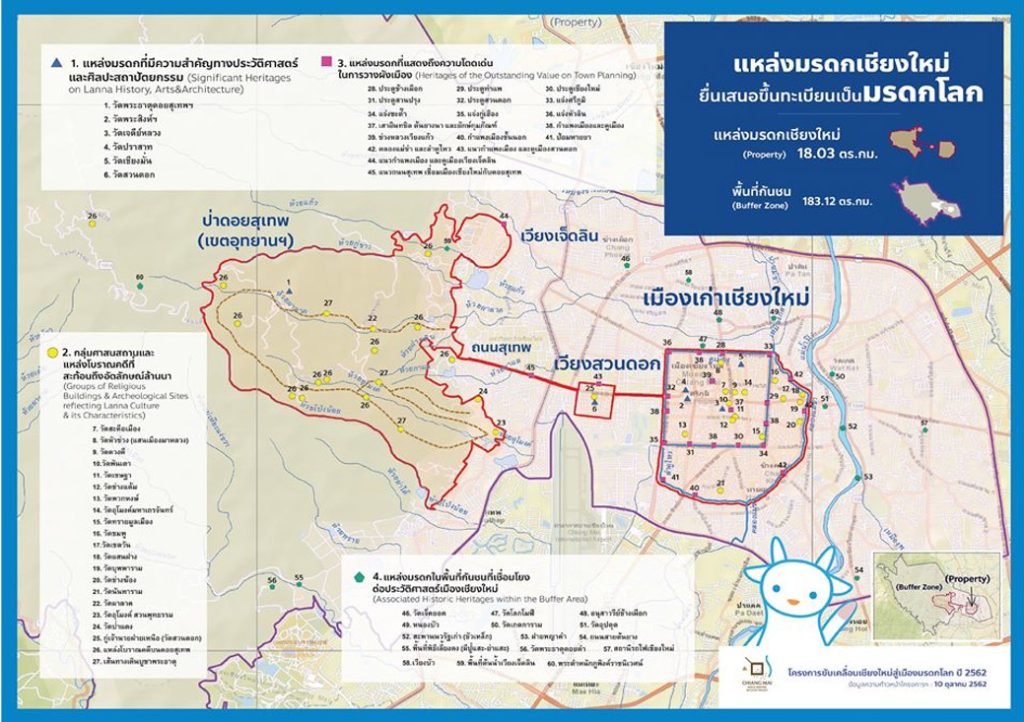

In February 2015, the Thailand National Committee for World Heritage submitted an application for the city of Chiang Mai to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. 1 While still on the tentative list, the organizing group plans to submit their final nomination dossier soon, possibly by the end of 2019. Across Southeast Asia, inscription on the World Heritage List is attractive, as it promises “international and national prestige, […] monetary assistance, and […] the potential benefits of heightened public awareness, tourism, and economic development.” 2 While Thai World Heritage sites, such as the Sukhothai and Ayutthaya, have mostly drawn on national identity and history, 3 this latest application in Thailand’s north—and other attempts that preceded it—reflect local or regional identity as much as national.

What is at stake here is a sort of northern response to the tensions between moradok (heritage) and yarn (community/neighborhood) Marc Askew identified in 1990s Bangkok. 4 Elevating abandoned ruins to national and global status is comparatively easy; in Chiang Mai’s case, the World Heritage nomination combines the physical remains of a politically potent past on one hand, and a living community on the other. What does this project mean for the identity of northerners, and the relationship between the north and Bangkok? How does this ongoing effort to preserve the heritage of the city fit into the longer history of regional identity in modern Thailand?

Lanna-ism

Chiang Mai’s application has potential consequences for the various groups with a stake in the future of the city. The groups behind the application include dedicated young architects, urban planners, and academics that broadly speaking fall under the banner of a certain kind of ‘localism’. In the case of Chiang Mai this is sometimes referred to as Lanna-ism, a neologism referring to the ancient kingdom of Lanna that controlled much of this region until the 16th century, and that provides the historical foundation for a local identity distinct from a ‘standard’ Bangkok or central-Thai-based identity. 5

Lanna-ism flows less from an organic connection to the historical kingdom of Lanna, and more from post-WWII efforts to claim a space for local political and cultural identity in cities like Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai. Local campaigns to build a university in the north, calls for the construction of statuary monuments to the kings of Lanna, and the reappearance of Lanna script throughout the city of Chiang Mai are all markers of this process. The urban heritage of Chiang Mai has always figured prominently in the formation and expression of Lanna-ism, partly because important spaces located in the city center were reconfigured and essentially colonized by the Bangkok state, and partly because of the long history of temples and palaces (khum) associated with the Lanna kings. Successfully adding the city to the World Heritage list would certainly elevate Lanna identity and Lanna-ness both nationally and globally.

The promotion of Lanna-ism comes in unexpected forms. As part of their campaign, the World Heritage working group held a mascot design contest, resulting in an incredibly cute rendition of the albino deer (fan phuak) that figures prominently into the founding myth of the city. This character, called Nong Fan, is intended to represent Chiang Mai and the World Heritage project—and perhaps even Lanna-ism itself.

The nomination includes a multitude of historically significant sites in and around the city of Chiang Mai, with an emphasis on the ancient history of the Mangrai dynasty and the ‘acceptable’ parts of Chiang Mai’s relationship with Siam, especially temples. 6 Yet, there are contested parts of the city center located within the project boundary but not named in the initial nomination. The two key museums in the city center that display the cultural identity of Lanna heritage are housed in historical buildings that were central to the internal colonialism of the Bangkok state—the government house (sala rathaban) and the district court (san khwaeng). In short, the nomination is part of a larger process aimed at reconfiguring the colonial center of the city as a showcase of local history, all within the acceptable framework of nationalist historiography.

Bangkok and the limits of history and heritage

World Heritage status offers a way for local identity, culture, and history to be preserved and promoted, but in the Thai context this means working within the limits of the Bangkok-dominated state. Past efforts to memorialize local history in urban space have also been shaped by Bangkok. For example, the famous “three kings” monument began as a single statue to Mangrai, the founding king of Chiang Mai and Lanna, but once the central government got involved, it changed into a monument that would connect the founding kings of both Chiang Mai and Sukhothai, thereby keeping local history firmly within the limits of the national. 7

Likewise, the recent path to the World Heritage list has involved a dance between center and periphery. The story begins in 2002 with Chiang Saen, Wiang Kum Kam, and Lamphun—smaller sites associated with the history of Lanna, all in need of preservation, and all with strong potential for increased tourism. 8 By 2008 Lamphun began pushinged ahead with an application for World Heritage listing. 9 In 2010 several academics began preparing for an eventual application for Chiang Mai. 10

At this point, national politics intervened. Activities related to UNESCO were halted later that year when conflict erupted over the status of Preah Vihear, an eleventh century Khmer temple on the border between Thailand and Cambodia that was inscribed on the World Heritage list in 2008. With an ongoing dispute over claims to the temple and its immediate surrounding, hyper-nationalist protests eventually led to actual conflict in 2011, and in June the Thai delegation withdrew from UNESCO in protest. 11 Work on any submissions to UNESCO in the north stopped. With the election that year of Yingluck Shinawatra, herself a khon muang from Chiang Mai, projects sped up rapidly. 12

Since any application to the World Heritage Committee needs the approval of the Bureau of International Cooperation within the Ministry of Education, 13 the contours of world heritage in the north would once again be shaped by the central state. By 2013, some officials suggested a ‘twin cities’ nomination, joining Chiang Mai to the Lamphun project. According to one academic, a serial nomination including Chiang Mai, Wiang Kum Kam, Lamphun, Lampang, and Chiang Saen would “represent the Lanna culture as well as sharing its natural and potential resources. It would also be easier to be included on the list than if it was proposed as a single city for a cultural heritage site.” 14 However, after finally passing national approval, only Chiang Mai’s application was submitted to UNESCO, and “Monuments, Sites and Cultural Landscape of Chiang Mai, Capital of Lanna” was added to the World Heritage Tentative List on February 9, 2015.

So what happened? While undoubtedly Chiang Mai could use protection and effective management of its urban heritage, world heritage status also presents risks associated with increased attention and tourism; smaller cities such as Lamphun and Chiang Saen, however, could use both protection and an increase in tourist dollars. There are clearly other economic concerns at play—Lamphun is in many ways more important to the state as a center for industrial investment, with two large industrial parks built very close to what would have been the protected heritage zone, and seeking to expand. 15 However, there are other historical reasons for Chiang Mai’s prime role in this particular expression of Lanna identity.

An overdeveloped city in an underdeveloped democracy

The problems facing Chiang Mai stem from government centralization and poor urban planning policies. Unlike other northern cities, Chiang Mai has maintained a close, and at times problematic connection with Bangkok. After the late nineteenth century, when the city was seen as a distant, even dangerous frontier, Chiang Mai was transformed into an outpost of the modern Siamese state, modeled partly on neighboring colonies in Southeast Asia. 16 With the local monarchy sidelined, the regional identity of Lao was discouraged, and Chiang Mai became a center of both a new ‘northern Thai’ identity, and Siamese administration. 17 In some ways, this connection has only deepened during and after the Thaksin era, with money and people flowing into the city from Bangkok and abroad. In the midst of these pressures, I argue we can view the World Heritage proposal as an attempt to address the problems of an overdeveloped city within a context of an underdeveloped democracy.

Consider the following answer from the director of Chiang Mai City Arts and Cultural Centre (one of the museums mentioned above), when asked why Chiang Mai is applying for World Heritage status now:

A: I think one of the things that the people of Chiang Mai and the working group have perceived together is that our city is changing rapidly – physically, socially and economically. These changes are both beneficial and at times inappropriate. Personally, I believe the time is right to process our bid for many reasons.

First, the people of Chiang Mai will have a chance to discuss and debate ways to preserve our city. Second, it is bringing about a change in public perception – a feeling that we can take responsibility, which I think is very important. In the past, if something happened, local people would call for agencies or organizations to take responsibility in resolving the issue. Now we are seeing many people and various networks willing and trying heartily to solve problems by themselves. They are volunteering their time, suggesting ideas, supporting the various aspects, and calling for collaboration with other groups. That’s why I think this is the right time for us to move ahead on this project. 18

Absent effective and responsive government, the community must act on its own; for Chiang Mai, the global discourse of world heritage offers a potential path for that action.

Conclusion

The history of World Heritage in Northern Thailand reflects key questions that shape regional identity in 2019 Thailand. First, what does the relationship between center and periphery look like today? Bangkok’s blessing is still needed, and continues to shape historical expressions of northern-ness or Lanna-ism. Inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List might motivate policy changes at the local level; however, the risk is that government officials ignore the hard work of the local community and the concrete policy changes listing might bring, and instead choose to see the World Heritage listing as just another mark of “global status.” 19 Second, what or who is included in ‘the North’—in short, why Chiang Mai, but not Chiang Saen, or Lamphun? While the Thai state has endorsed Chiang Mai for elevation to UNESCO’s global stage, other Lanna sites deserving of attention and conservation remain underappreciated, or even ignored.

Chiang Mai’s application for inscription is, of course, taking place in illiberal, undemocratic times, with pressures on northerners to demonstrate their loyalty to the state and new king. While elections of a sort returned to Thailand in May 2019, without effective local representation, such as elected governors, 20 local control of local identity seems a distant hope. The appeal to global discourses of World Heritage, however, just might be an opportunity for some to challenge, even if slightly, the past and present of a hyper-centralized Thai state.

Talor Easum

Indiana State University

Read “Sculpting and Casting Memory and History in a Northern Thai City” in Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, Issue 20, September 2016

Banner Image: Aerial view of sunset landscape ring road and traffic, Chiang Mai City,

Notes:

- Monuments, Sites and Cultural Landscape of Chiang Mai, Capital of Lanna,” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6003/; Tus Werayutwattana, “Our Journey to Becoming a UNESCO World Heritage City,” Chiang Mai Citylife, March 1, 2019, https://www.chiangmaicitylife.com/citylife-articles/journey-becoming-unesco-world-heritage-city/. ↩

- Lynn Meskell, “UNESCO’s World Heritage Convention at 40: Challenging the Economic and Political Order of International Heritage Conservation,” Current Anthropology 54, no. 4 (August 1, 2013): 483, https://doi.org/10.1086/671136. ↩

- Victor T. King and Michael J.G. Parnwell, “World Heritage Sites and Domestic Tourism in Thailand: Social Change and Management Implications,” South East Asia Research 19, no. 3 (September 1, 2011): 381–420, https://doi.org/10.5367/sear.2011.0055; Maurizio Peleggi, The Politics of Ruins and the Business of Nostalgia (Chiang Mai, Thailand: White Lotus Press, 2002). ↩

- Marc Askew, “The Rise of ‘Moradok’ and the Decline of the ‘Yarn’: Heritage and Cultural Construction in Urban Thailand,” Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 11, no. 2 (1996): 183–210. ↩

- See, for example, Anek Laothamatas and อัครเดช สุภัคกุล, ล้านนานิยม: เค้าโครงประวัติศาสตร์เพื่อความรักและภูมิใจในท้องถิ่น (สภาบันคลังปัญญาค้นหายุทธศาสตร์เพื่ออนาคตไทย มหาวิทยาลัยรังสิต, 2014); สุนทร คำยอด and สมพงศ์ วิทยศักดิ์พันธุ์, “‘อุดมการณ์ล้านนานิยม’ ในวรรณกรรมของนักเขียนภาคเหนือ (Lannaism Ideology in Literature of Northern Thai Writers),” Journal of Liberal Arts, Maejo University 4, no. 2 (2016): 52–61. ↩

- “Monuments, Sites and Cultural Landscape of Chiang Mai, Capital of Lanna,” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6003/. ↩

- For more information on the role of statues in this history, see my “Sculpting and Casting Memory and History in a Northern Thai City,” Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, no. 20 (September 2016), https://kyotoreview.org/issue-20/casting-memory-northern-thai-city/. ↩

- Wat Phra Mahathat Woramahawihan in Nakhorn Sri Thammarat, for example, made it to the tentative list one year after Yingluck took office. “Wat Phra Mahathat Woramahawihan, Nakhon Si Thammarat,” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, accessed November 15, 2019, https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5752/.“Monuments, Sites and Cultural Landscape of Chiang Mai, Capital of Lanna,” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6003/. ↩

- Pensupa Sukkata, Interview, July 12, 2019. ↩

- สมโชติ อ๋องสกุล and สำนักงานพัฒนาพิงคนคร (องค์การมหาชน), เชียงใหม่ 60 รอบนักษัตร: อดีต ปัจจุบัน และอนาคต (Chiang Mai at the 60th anniversary of the zodiac cycle : its past, present and future), (Chiang Mai, สำนักงานพัฒนาพิงคนคร, 2016, 333–41. ↩

- “Thailand Withdraws From World Heritage Convention Over Temple Dispute,” VOA, https://www.voacambodia.com/a/thailand-withdraws-from-world-heritage-convention-in-temple-dispute-with-cambodia-124589479/1358343.html. ↩

- Wat Phra Mahathat Woramahawihan in Nakhorn Sri Thammarat, for example, made it to the tentative list one year after Yingluck took office. “Wat Phra Mahathat Woramahawihan, Nakhon Si Thammarat.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5752/. ↩

- “Bureau of International Cooperation, Ministry of Education, Thailand,” สำนักความสัมพันธ์ต่างประเทศ สำนักงานปลัดกระทรวงศึกษาธิการ, https://www.bic.moe.go.th/index.php. ↩

- Kreangkrai Kirdsiri, deputy dean for planning and research affairs at the Faculty of Architecture of Silpakorn University, quoted in Jintana Panyaarvudh, “Chiang Mai Will Get Unesco World Heritage Listing ‘Only If Thailand Pushes for It,’” The Nation Thailand, March 1, 2015, https://www.nationthailand.com/national/30255138. ↩

- Chatrudee Theparat, “Lamphun Asks Ministry for More Land to Expand Industrial Zone,” Bangkok Post, https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/1567622/lamphun-asks-ministry-for-more-land-to-expand-industrial-zone. ↩

- Ronald Renard, “The Image of Chiang Mai: The Making of a Beautiful City,” Journal of the Siam Society 87, no. 1 (1999): 87–98. ↩

- Taylor M. Easum, “Imagining the ‘Laos Mission’: On the Usage of ‘Lao’ in Northern Siam and Beyond,” The Journal of Lao Studies, Special Issue (2015): 6–23. ↩

- ]Emphasis added. Interview with Mrs. Suwaree Wongkongkaew, in “Chiang Mai’s Best Opportunity to Become a World Heritage City,” Chiang Mai World Heritage Initiative Project, http://www.chiangmaiworldheritage.net/detail_show.php?id=69&lang=e ↩

- Marc Askew, “The Magic List of Global Status: UNESCO, World Heritage and the Agendas of States,” in Heritage and Globalisation, by Sophia Labadi and Colin Long (New York, NY: Routledge, 2010). ↩

- “Why Can’t Thailand’s Provinces Elect Their Own Governors?,” The Isaan Record, May 1, 2018, https://isaanrecord.com/2018/05/01/why-cant-thailands-provinces-elect-their-own-governors ↩