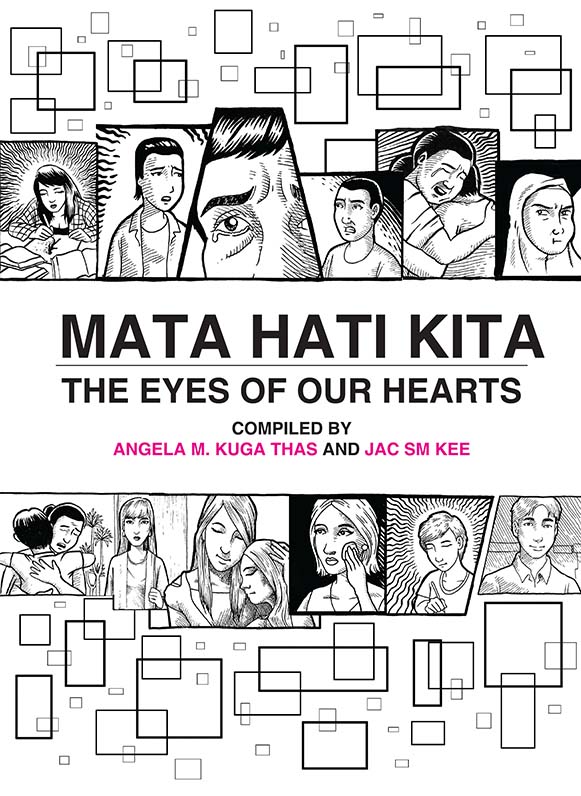

Mata Hati Kita, The Eyes of Our Hearts

Compiled by: Angela M. Kuga Thas and Jac SM Kee

Petaling Jaya: Gerakbudaya Enterprise, 2016, 142 pages

The recent widespread impression that religion, especially Islam, is to blame for the policing of sexuality in Malaysia is associated with the fact that two trends, Islamization and increasingly tightened regulation of bodies, have obviously been running parallel to each other over the past three decades in the country. While it is not untrue that recent tightened state control of non-heteronormative sexuality is attributable to Islamization, the history of sexuality regulation actually has a much longer history than that of Islamization suggests.

For instance, the criminalization of “deviant” sexuality and “unnatural sex”, as in Penal Code 377, is a century old colonial legal legacy, which can be traced as far back as 1870s. Despite its long history, its existence was not widely felt until the spectacular trial of Anwar Ibrahim, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) expelled opposition leader, for his alleged “deviant” sexual conduct in the theater of court in late 1990s. Equally significant is the coverage of state controlled newspapers and TV stations of the trial, without which, Penal Code 377 and the criminalization of “deviant” sexuality would not have become as popular as they are today.

However, it was not until recently have Islamic interpretation begun to overtake secular ones in policing and penalizing unorthodox sexuality, as rivaling Islamic forces seek to assert and reinvent Islamic authority in the governance of people’s everyday lives, especially Muslims’. Ironically, contemporary Syariah Court system has its root in the origin of Muhammadan laws during colonial period. The similarity between secular offences and Syariah offences in regards to provisions related to body and moral policing further points us to the fact that both systems share colonial origin and diverge little from each other (Tan 2012). In other words, both secular and Syariah laws find their ways in policing sexuality, albeit in different periods in Malaysia’s history. Seeing it from this longue durée perspective, Islamization is merely a trend that upholds Islamic interpretation over secular one to be the authoritative referent over people’s everyday lives, especially regarding sexual morality.

It was against this background of increasing tightened regulation of body and non-heteronormative sexuality that Mata Hati Kita, The Eyes of Our Hearts brings out kisah benar or real stories of 24 lesbians, bisexual women and trans people in order to make the lives of sexual minorities more visible. Interestingly, stories of gay men are not included in this collection. Compared to other sexual minorities, gay men have been relatively more visible and vocal. The Eyes of Our Hearts is thus a timely space for those who are more marginalized within the sexually marginalized community itself to narrate their stories.

These real stories, compiled by human and sexual right activists Angela M. Kuga Thas and Jac SM Kee, reflect lesbians, bisexual women and trans people not merely as “victims” of a system that criminalizes them for who they are, but “people who are finding their way towards themselves and their place in a world that refuses to see that things aren’t always all that solid” (p.vii). Different from Body2Body: A Malaysian Queer Anthology, a collection of 23 queer fictions and real stories written by urban middle class Anglophone elites and jointly edited by two artists Jerome Kugan and Pang Khee Teik in 2009, all stories in The Eyes of Our Hearts are told in first-person narratives by narrators from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds and come from different parts of the country. As indicated in the bilingual title of the book, some stories are told in a mixture of Malay and English (some narrators evidently read and speak Mandarin), reflecting both the voices of the narrators and the polyglot landscape in the country. Each story is also summarized and depicted in comics, making the book more attractive and readable to young people in the country.

As a collection of real stories, this book gives the reader a picture of multiple co-existing realities, some contradictory to each other, about the lives of sexual minorities. For instance, while criminalization, discrimination and harassment of “deviant” sexuality are real and causing stress in the everyday lives of these narrators, jealousy and competition in work and in intimate relationship are just as common as a source of stress for many. Also, different people respond and react differently to criminalization, discrimination and harassment. Some internalize the hatred they have experienced, as indicated in self harm; some learn to love one-self; some strive to live up to what the mainstream society defines as desirable, such as being hard working, in order to not give the sexual minority a bad name. There is no one single correct response to discrimination as each response speaks to the trajectory of the individual’s lives.

While making the lives of sexual minorities more visible is one of the major aims of this book, it should be noted that, there is a paradox regarding the visibility of sexually marginalized community. As a matter of fact, criminalization of “deviant sexualities” often involves making visible what “deviant sexualities” are to the eyes of law enforcers for the purpose of policing and penalizing undesired sexualities. A project like this book, which makes visibility a method of connection for non-heteronormative people who have experienced discrimination and harassment, is as essential for aggregating interest and political mobilization against a body policing system. Nevertheless, the fact that all narrators narrate their stories anonymously, as we see in the collection, indicates that this visibility project is just a beginning for constructing a safe and comfortable space for non-heteronormative sexualities.

Taken together, these stories are about hope and despair, love and hatred, desires and longings. They are personal as much as they are political as the wider society finds its ways to define who one is, what kind of lives are desirable and what not. As Jac SM Kee puts in the preface: “Some of these stories will break your heart. Some will make you feel like you are not alone as you see parts of yourself within them. Some will make you become still with awe.” This is a book where people who are finding ways to see their place(s) in the world will be able to relate to.

Reviewed by Por Heong Hong

Research Fellow, University of Malaya

References

Jerome Kugan and Pang Khee Teik (eds). Body2Body: A Malaysian Queer Anthology. Petaling Jaya: Matahari, 2009.

Tan, Beng Hui. Sexuality, Islam and Politics in Malaysia: A Study of the Shifting Strategy of Regulation. National University of Singapore: Unpublished PhD Thesis, 2012.

Malonu skaityti!