Detours to Paradise (Sincerely Yours)

Produced and directed by Rich Lee. Written by Shu-Wen Hu, Mr. Lee and Shou-Qian Ho.

Production year: 2009.

Running time: 118 minutes.

This film is directed by Rich Lee, a cram-school teacher whose dream was to make a film, it is his first work. Focusing on Setia, a female Indonesian migrant worker (starring Indonesian actress Lola Amaria), and Yong, a male Thai migrant worker (starring Thai actor Banlop Lomnoi), this film shows Southeast Asian migrant workers’ life in Taiwan 1 from a wide range of aspects. Besides, it shows the life of Taiwanese counterpart through those ‘foreign workers’ eyes’.

Migrant workers are often stigmatized by the mass media in Taiwan. This film shows the many ‘illegal’ actions of those migrant workers. The ‘runaway workers’(逃 跑外勞), who come to Taiwan as legal workers but leave their workplaces to become ‘illegal’ workers are the protagonists of this film. In addition, the sexualities of migrant workers which are heavily regulated by the government (especially in the case of female migrant workers, see Lan 2008), challenge the order that treat them only as physical labor. Along with the ‘runaway’ and ‘sexual’ body beyond control, many other ‘illegal’ actions are shown in this film: illegal sexual prostitution, changing names to extend the time-limit of working permit in Taiwan, stealing motorbikes or money, or even stealing the metal cords in the construction sites to sell.

[quote]

Many kinds of resistance are portrayed in the movie

[/quote]

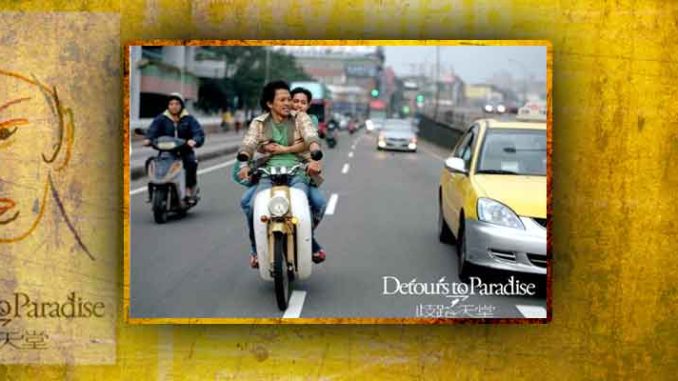

However, this film shows sympathy for those ‘illegal’ actions by looking at the social relationships among these works, and by comparing them with their Taiwanese counterparts. On the one hand, we can see those migrant workers doing ‘illegal’ actions for their friends or families. The money earned by sex work or stealing is for Setia’s family in Indonesia, or sent by Yong to his friend for his sister’s education in Thailand. The motorbike the Thai worker stole enables Yong and his Indonesian girlfriend, Setia, to travel through Taoyuan City. 2 The ‘illegal’ actions can be also read as one kind of ‘resistance’ to the control of body by the law and the control of labor by the state. The make-up and consumption that Setia and other female migrant workers adopt on the ‘back stage’ (outside the workplace) can be read as resistance to the ‘front stage’ 3 of their workplaces. On the other hand, the film tells us that those ‘illegal’ actions are not only done by those ‘foreign’ workers, but by Taiwanese as well. Brokers for runaway workers, metal cord thieves, and even the politicians are also connected with human trafficking in this film, which is done by Taiwanese.

Another main theme of this film is the ‘enclaves’ made by those Southeast Asian migrant workers in Taiwan. First, this film takes us to those areas where migrant workers get together, such as Thai/Indonesian restaurants and hotels around Taipei/Taoyuan/Jungli Railway Station, Thai pubs, mosques, and others. Along with these places, the friendship and network of migrant workers are also shown in this film. The relationship between Yong and Setia, the friendship among female workers from either Southeast Asia (in this film, mainly Thai and Indonesian) and Mainland China, and even relationships with Thai or Cambodian employers (who may come to Taiwan by marriage) are all included in this film. Interestingly, ‘enclaves’ made by those migrant workers are not confined to one specific ethnicity/nationality, but allow for multiple interactions of people from different origins. And they talk to each other in a mixture of Thai, Indonesian, Chinese, and even Taiwanese—in effect challenging the conflation of language = ethnicity = nationality.

[quote]

The movie highlights the ridiculous of certain Taiwanese cultures

[/quote]

Although focusing on the lives of migrant workers, the most fascinating thing about this movie is its featuring of ‘marginal’ Taiwanese’ life as contrasting device to reflect the ‘marginal’ stigmatization of migrant workers. It theatrically highlights the ridiculousness of those Taiwanese cultures or life. For example, the Taiwanese employers of Setia are an old man who is at the end of his life and a has-been actress, who began life as an impoverished worker before becoming famous and then sinking into obscurity. Yong also met a young gay man on the train who paid him to have for sex. Compared to the sick, hopeless, and lonely Taiwanese in this film, migrant workers appear to lead more ‘normal’ lives. Postmodernism brought about Taiwanese traditions, such as ‘funeral strip dances for the dead (電子花車)’ and ‘Electric-Techno Neon Gods (電音三太子)’, are introduced and seen through the eyes of southeast Asian migrant workers, thereby reversing the gaze of the Taiwanese mass media or academic researchers.

By showing the illegal, marginal, ridiculous lives of Southeast Asian migrant workers and their Taiwanese counterparts, as well as the friendships and networks that support them, this film makes us rethink the differences between ‘us’ and ‘them’. Although the police appear intermittently throughout the film as symbols of law and order, interfering with migrant workers’ lives, we can still see these migrant workers’ struggling for dignity and a better life beyond state control and beyond the limits of nationality/ethnicity. Unlike academic articles that focus on specific aspects of migrant workers’ lives, this film tries to convey, in panoramic as well as close-up views, the multifaceted and complex entanglement of migrant and Taiwanese lives. Of course, we can criticize the film for touching on those issues shallowly, but it does illuminate the colorful lives of Southeast Asian migrant workers—as opposed to mere “labor forces” —in Taiwan.

Reviewed by Lin Yu-Sheng

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 13 (March 2013). Monarchies in Southeast Asia

References

Lan, Pei-Chia (藍佩嘉). 2002. 跨越國界的生命地圖:菲籍海外家務勞工的流動與 認同 (A Transnational Topography for the Migration and Identification of Filipina Migrant Domestic Workers). 台灣社會研究季刊 (Taiwan: A Radical Quarterly in Social Studies) 48:11-59. (in Chinese)

. 2008. Migrant Women’s Bodies as Boundary Markers: Reproductive Crisis and Sexual Control in the Ethnic Frontiers of Taiwan. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 33(4):833-861.

Wang, Chih-hung (王志弘). 2002. 移⁄置認同與空間政治:桃園火車站週邊消費族 裔地景研究. (Dis/placed Identification and Politics of Space: The Consumptive Ethnoscape around Tao-Yuan Railroad Station). 台灣社會研究季刊 (Taiwan: A Radical Quarterly in Social Studies) 61:149-203. (in Chinese)

Notes:

- Until now, only contract guest workers from six countries are legal in Taiwan: Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, Philippines, and Mongolia. And of those laborers, more than 90% come from Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Philippines. ↩

- Taoyuan City and Jungli City (discussed below) belong to Taoyuan County, which has the most number of migrant workers in Taiwan. Around the railway station of Taoyuan and Jungli can be found many restaurants and banking services for migrant workers who get together there. These cities have become a holiday destination for migrant workers. See Wang 2006. ↩

- Taoyuan City and Jungli City (discussed below) belong to Taoyuan County, which has the most number of migrant workers in Taiwan. Around the railway station of Taoyuan and Jungli can be found many restaurants and banking services for migrant workers who get together there. These cities have become a holiday destination for migrant workers. See Wang 2006. ↩