This year saw the premiere of Itumba ang mga Adik (Kill the Addicts) in the Philippines. Shot in streets across the country, from narrow alleys to cramped rooms, the controversial film stars vigilantes, (suspected) drug users and dealers, crime syndicates, and innocent civilians. It has been a bloody tale of crime and punishment.

There is a dark sense of deja vu about this spate of killings, for they were once the stuff of post-War Filipino action movies. It’s worth revisiting such films because they resonate strongly with current debates and dilemmas about justice, democracy, and human rights. One title says it all: Iyo ang Batas, Akin ang Katarungan (The Law Is Yours; Justice Is Mine, 1988).

Filipino Action Movies were a popular medium through which many Filipinos grappled with and resolved a problem: of how justice can be obtained when due process does not work, especially for the poor and marginalized. How does one get justice when its very agents are in cahoots with the criminals? What if the law enforcer and the criminal are one?

Plots of Pinoy Action Movies are formulaic; they essentially feature a corrupt government official or a crime boss (or both who are in cahoots) who does the action hero some injustice. To much applause, the hero later gets his revenge and rectifies everything by killing the official and/or the crime lord.

The solution is as simple as the plot: Kill. Without due process. Without any trial. Without human rights.

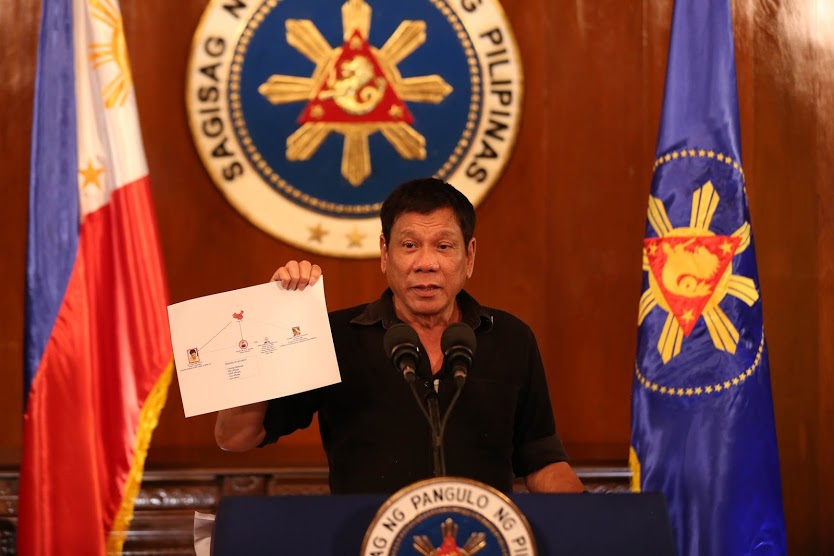

The golden age of action movies is long gone, but they appear to echo what’s taking place in the streets. Are Filipinos living in a real-life action movie? Is President Duterte’s monicker, Dirty-Harry, well-deserved as a crime-fighting action hero? Do the perpetrators of the kill-for-justice cases play a supporting cast, while (even suspected) drug users and pushers are the infamous villains? Are the former channeling the ghosts of action heroes past?

This is not a case of art imitating life, or vice versa. For one thing, the perpetrators behind the killings hardly seem heroes to many. Plus, some of the recent killings may have been done not to seek justice, but simply to silence the victims and keep them from incriminating others. Despite this and other differences, a similarity between life and cinema is striking enough: everything is or has to be settled by guns.

Both action films and the kill-for-justice cases resonate in, and resolve, a society that many Filipinos are all too familiar with: a lack, if not absence, of a fair and effective criminal justice system; and they mirror the dominant logic, not of due process or democracy, but of force and violence.

In Iyo ang Batas, Akin ang Katarungan, the hero, Dante Reyes, could have pursued due process but does not. He knows that doing so will not work because the law enforcers are in league with the criminals. The mayor himself leads them. Proudly stating that “In this town, I am the Law,” the mayor then later orders the his goons to take care of Dante’s family, who all end up dead. He, the mayor, then steals their land, which they’ve tilled for generations. The local police chief, who’s a friend of Dante and could have helped, simply flees to the mountains to join an armed movement against the mayor. It is up to Dante, and only him, to get justice for his family. And so he does. When he kills the mayor in the final scene.

The killing of drug users and pushers has been justified in a similar way. Like the mayor, they are perceived as a menace to society, perpetrators of unspeakable crimes like rape and murder. Also, the deaths have been condoned because they have led to cleaner, safer streets. And because they sidestep the deficiencies and inconveniences of due process, said to be frustratingly ineffective, if not abused and distrusted. One government official has remarked that suspending the writ of habeas corpus would make the drug war easier. Either way, just as it was in the movies, the solution is to kill.

Swift and simple, violence streamlines the delivery of justice, and offers a solution to the problems bedevilling the justice system. But the solution is also a part of the problem it seeks to address. It’s a crime in response to another (alleged) crime. It traps Filipinos in a never-ending cycle of violence, where the heroes — in movies and in real life — are villains too, both of whom have blood on their hands.

Most importantly, if the problems and realities posed by Filipino Action Movies of the last century resonate so strongly today, does it mean that Filipinos’ sense and institutions of justice have evolved so little, if at all? Are we stuck in a time warp, imprisoned in the violent, kill-for-justice logic of the films?

EDSA One in 1986 was supposed to be the triumph of democracy, due process, and human rights. But thirty years on, why is violence the only or best answer some can think of to the problem of drugs, crime, and justice? Have things really gotten so desperate that Filipinos need to kill to bring about justice? Or have they become part of the problem precisely because they’re resorting to such violence to do so? Moreover, why are Filipinos in an uproar over the killings today, when activists, journalists, lumad leaders, peasant organizers, and many countless others have always been harassed, tortured, and executed, their stories forgotten and largely ignored? And why, as many have pointed out, do the poor comprise the majority of targets?

The violence today and this rather selective sense of justice are tragic and should be condemned in no uncertain terms, but they also signal, among other things, the failure to consolidate rule of law and democracy. For most of their history, Filipinos have had little taste of democracy’s institutions in ways where they could believe in and live by its ideals. It has not taken a deep enough root in Philippine society, such that Filipinos could trust in its efficacy and believe that there are ways to effect justice (and solve the drug problem) — poverty alleviation, education, health programs — other than violence. It is not surprising that our culture has few legal dramas and police procedurals. Maybe Filipinos simply do not have enough faith in the justice system for such stories to be credible. This long-standing democracy deficit, as it were, makes the alternative — no, the standard — quest for justice so difficult to achieve yet more urgent than ever.

Even as Filipinos rightfully reject violent justice, they must also reckon with the dilemma recognized by Filipino Action Movies: what if, like Dante Reyes, they cannot resort to due process and seek justice from who should dispense it but does not or could not?

Similarly, in their faith in and call for due process and for investigations into the killings, how much can Filipinos actually rely on widely perceived corrupt and ineffective institutions to remedy a problem that it is suspected of being a part of? If the politicians, police officials, and others named by President Duterte last August are part of a drug network, and if the suspicions (that police officers themselves are behind some of the killings) are true, to what extent can Filipinos expect law enforcement to help address the problem when part of its personnel are perceived to be participants therein? If President Duterte’s list is indeed true, the moral lines — between cop and criminal — have indeed blurred, as just as they did in the movies. It’s no longer the case where the police are completely clean, and only the criminals are dirty. What if they are now one and the same? And how can Filipinos tell who’s good cop and bad cop?

A true-to-life film has been unfolded before the Filipinos, and its plot will only thicken. Will it become bloodier, like the action movies of old, or can the Filipinos the people, like the heroes we could and should be, turn the story around and change the narrative? Can they adopt creative yet law-abiding means of finding justice, and come up with a happily-ever-after ending? Or if that’s too much to ask, at least one with no more dead bodies.

Janus Isaac Nolasco

Janus Isaac Nolasco is University Researcher at the Asian Center, University of the Philippines Diliman. He is also Managing Editor of Asian Studies: Journal of Critical Perspectives on Asia.

YAV, Issue 20, Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. December 2016

nice post