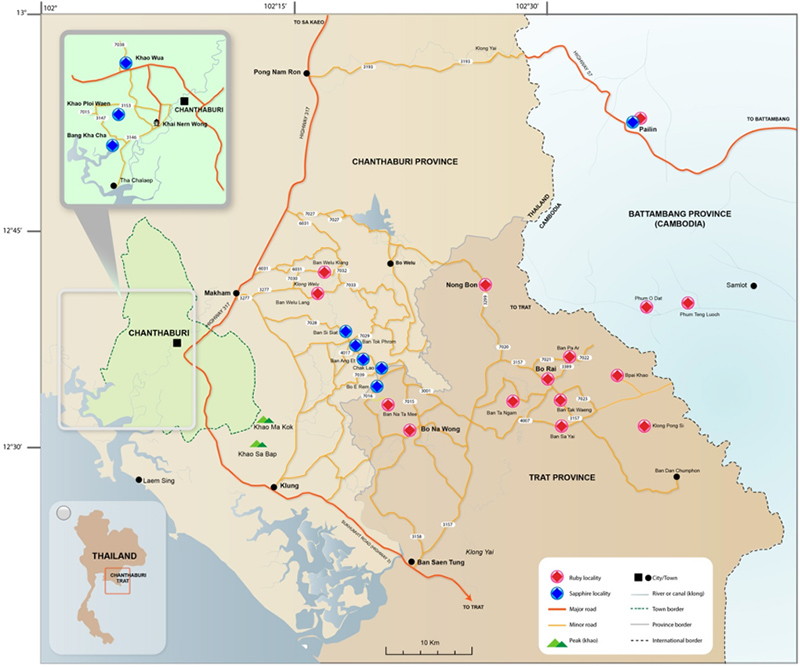

The city of Chanthaburi in the Thai-Cambodia borderlands is small, but has played a significant role in the history of Thailand and in the history of gem trade throughout the world. Located 250 kilometers to the east of Bangkok, the Thai-Cambodia borderlands have traditionally produced world-class and yellow sapphires (GIA 2015).

The region is especially famous for its sapphire, which comes in yellow, blue, and black star varieties. These all share the same basic chemical composition, that is, aluminium oxide – the difference of colour due to various chemical traces make these distinct. Locally, gem mines of the Thai-Cambodia border are known as Bo Ploy. The Khao Ploy Waen or literally ‘hill of gems,’ which is one of the main mining areas of Chanthaburi (the other being Ban Ka Cha), is situated about 10 kilometers from the city in a scenic jungle area located on slightly elevated dead volcanic plugs. On the top of the hill, there is a Buddhist pagoda. In local narratives, the location seems like the setting for an Indiana Jones movie, a perfect location for the pursuit of ‘hidden treasure.’

Gems were traditionally mined through artisanal methods by the Shan community of Myanmar, locally known as Gula or Kula miners. This community migrated to and settled in this region, and have today become specialists in gem mining over a period of more than one and a half centuries (Louis 1894).Though most of the mines have been exhausted now, due to mechanized mining, some small scale mining still continues here.

Gem mining in the Thai-Cambodia borderlands remains one of the few lucrative professions for mine owners who can get quick monetary returns for their investment. For the workers, by contrast, it is a relatively stable livelihood with better wages than what they get in farming, which adds a sense of upward mobility to the otherwise poor peasant-labour population (Hughes 2017). While there is a slow agrarian transition in Thailand whereby peasant-labours move to the cities, surprisingly the larger part of this population still stays in village and takes part in region specific activities like shrimp farming (Flaherty, Vandergeest and Mille 1999), fruit orchards and plantation, and Gem mining in places like Thai Cambodia borderlands. There is an increasing global trend of the rise of precarious and informal labour (that is labour engaged in precarious and transient livelihoods) engaged around mining capital (Bryceson and Geenen 2016) and peasant miners (Roy Chowdhury and Lahiri-Dutt 2016) and Gem mining Chanthaburi fits into that global circuit.

Here is a look of the lives of mining labours and the semi-mechanised gem mines that they work in. Mechanized gem mining started as early as the 1890’s, when the Anglo-Italian Exploration Association Co. received a concession from the King of Siam in 1889 for prospecting the Chanthaburi and Trat provinces. The concession was later transferred to a British company named The Sapphires and Rubies of Siam Ltd. in 1890 (UN 2001; p. 97).

Modern mechanized and semi-mechanized mining from 1962 to 1996 rapidly depleted this borderland of its gems through large-scale and intensive operations of open cast mining under high pressure water hoses. These new mining techniques resulted in stripping the countryside of its vegetation (Duggleby 2014). These mining units are owned by Thai nationals who do business with gem and jewellery companies, wholesalers, and multinational companies. Production units owned by large multinational companies including Pandora Jewelry from Belgium and Emerald Mines and Company Ltd from India take mined gemstones for production in Bangkok (Navneet Gems 2017).

Abundant gems were found in this region until the 1990’s in the Sapphire-rich lateritic grounds of Khao Ploy Waen, where now only few semi-mechanized mines operate (fieldgemology.com, 2, 2010). Due to mechanised mining, large puddles are formed in this region during the monsoon season. As a result, this is a breeding ground for malaria. These conditions raise the risk of malaria contraction and increase the likelihood of accidents. Yet despite ongoing challenges, people carry on mining in the hope of windfall profits.

Finding gemstone through artisanal mining has always been about speculation, hard work and luck. Despite the industrialization of the mines, these profits are not guaranteed. One of the supervisors shared an excavating principle: “Finding a good stone is a mix of luck and skill, but it is more about luck. You don’t find a stone; the stone finds you.”

Due to exhaustion of the gemstone reserve in the top-soil of this region, informal mining does not offer a steady flow of money like it once did. There has been a shift to semi-mechanised mines, which in turn, has brought about a certain degree of alienation among workers. Before commencing work, one of the workers summed up the irony of his engagement, “We find so many stones, sapphires, garnets, and many more, but we don’t keep them. They don’t belong to us; we are just labours.”

Mining labor is still often the best hope local workers have to lift their families from poverty, despite the uncertainty this work provides. A worker in the mine shared his aspiration, “I often dream that one day I will find a big Butsarakaam, as big as the moon, earn a lot of money by selling that, and I will send my son to a good college”. In a place like Chanthaburi where the majority of these mine workers come from, farming communities are cash poor, and gem mining is a source of cash and the possibility of social mobility for the miners.

The future of semi-mechanized mining in Khao Ploy Waen remains unclear; possibly when the resources dry up, the town will turn into a ghost town like some other areas of Bo Rai. The workers may move on to another regions with the continued hope of finding economic opportunities for their families.

Arnab Roy Chowdhury &Ahmed Abid

Photography: Sreedeep

Arnab Roy Chowdhury is a Postdoctoral Fellow, Public Policy Department, National Research University-Higher School of Economics (NRU-HSE), Moscow, Russian Federation. Prior to this he was a Visiting Assistant Professor in IIMC, Calcutta. He received his PhD in Sociology from the National University of Singapore (NUS) in May 2014.

Ahmed Abid is a journalist from Bangladesh. He is former research and teaching assistant at NUS and currently pursuing PhD from Western Sydney University. He works on Human Rights issues and Migration in South and South East Asia.

Sreedeep is currently a Researcher with the C-PACT, Shiv Nadar University, India. He is an independent photographer with a wide range of visual interests. His academic interests include Contemporary Visual, Material and Virtual Cultures; Body, Image and its Representations; Industrial Ruination and Planned Obsolescence.

Map © Richard Hughes & Maneekan Sahachat/Thaigem.com.

Source: http://www.ruby-sapphire.com/chanthaburi-history-of-moontown.htm

Reference:

Apsara: Ruby Mining at Bo Rai, Trat. https://apsara.co.uk/index.php/articles-1/ruby-mining-at-bo-rai.html

Bryceson, D., & Geenen, S. (2016). Artisanal Frontier Mining of Gold in Africa: Labour Transformation in Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo. African Affairs, 115(459), pp. 296–317. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adv073

Chanthaburi, Pailin and Meeting the MJP. Field Gemology.com 1 (Accessed on 07 June 2017). http://www.fieldgemology.org/blog_display.php?id=

Chowdhury, A. R., & Lahiri-Dutt, K. (2016) The Geophagous Peasants of Kalahandi: Depeasantisation and Artisanal Mining of Coloured Gemstones in India. Extractive Industries and Society, 3(3), pp. 703–715.

Duggleby, L. (9 August, 2014) Tricks and stones: the gem traders of Chanthaburi. http://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/article/1569045/tricks-and-stones

Flaherty, M., Vandergeest, P., and Mille, P. (1999) Rice Paddy or Shrimp Pond: Tough Decisions in Rural Thailand, World Development, 27(12), pp. 2045–2060.

Hughes, R. W. History of Chanthaburi and Pailin. (Accessed on 07 June 2017). http://www.ruby-sapphire.com/chanthaburi-history-of-moontown.htm

Louis, H. (1894) The Ruby and Sapphire Deposits of Moung Klung. Siam Mineralogical Magazine, 10(48) pp. 267–272. http://www.palagems.com/thai-ruby-henry-louis/

O’Donoghue, M. (1988). Gemstones . USA: Chapman and Hall. http://bit.ly/2iaC3Zo

Pholdhampalit, K. (2017). The land of Precious Stones, The Nation , April 09, 2017, The Sunday Nation. http://www.nationmultimedia.com/news/life/art_culture/30311697

Shore, R. (2013) Bargaining for Gems in Chanthaburi, Accessed April 30, 2018. https://www.gia.edu/gia-news-research-Chanthaburi-gem-market

Mineral Resources of Thailand. (UN 2001, p. 97). https://books.google.co.in/books/about/Mineral_Resources_of_Thailand.html?id=WGWNypkq6wkC&redir_esc=y

Navneet Gems (2017). http://www.navneetgems.com/

Sudarat, S., Sangsawong, S., Vertriest, V., Atikarnsakul, U., Raynaud-Flattot, V. L., Khowpong, C., & Weeramonkhonlert, V. A Study of Sapphire from Chanthaburi, Thailand and its Gemological Characteristics. https://www.gia.edu/gia-news-research/sapphire-chanthaburi-thailand-gemological-characteristics

Thailand: A Visit to the Chanthaburi Sapphire Mines. http://www.fieldgemology.org/blog_byKey.php?key=Khao%20Ploy%20Waen