In 2014, for the first time, Indonesia appointed a female diplomat, Retno Marsudi, to become Indonesian new minister of foreign affairs. A couple years later, Indonesia set its two female diplomats to deliver Indonesian replies to West Papua issues that were brought by Pacific countries at UN General Assembly (UNGA).

During the 71st session of the UNGA, where some Pacific Countries condemned human rights violations that took place in West Papua, Nara Masista Rakhmatia, a female diplomat at Indonesia’s permanent mission to the UN, was appointed by the Indonesian government to give a speech to respond to the condemnation.

In the next year, Ainan Nuran held the same position. During the 72nd session of the UNGA, she delivered a reply to the leaders of the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, and Saint Vincent and Grenadines who condemned human rights violations in West Papua and stated their support for West Papua’s right to self-determination.

The presence of the Indonesian female diplomats in the key position of foreign policy making as well as to hold sensitive issues, such as human rights violations in West Papua, indicates the improvements in gender awareness and equality in Indonesian foreign policy.

Additionally, a senior Indonesian female diplomat also acknowledged that the current condition is more welcome for female diplomats than years ago. She said, in the past, female diplomats had to put in twice the efforts to be recognized (Jakarta Globe, 2018).

What is the Cause?

Gender socialization plays a vital role in the making of gender awareness in society, including the awareness over the involvement of women in politics, especially in international politics or foreign policy. Gender socialization is the process that explaining individual how to act in their society to be based on gender differentiation. From this socialization, humans learn how to behave and what roles they have according to their sexes. Gender socialization operates through different ways, such as family, friends, schools, media, and so on. Gender socialization potentially preserves gender stereotype that constrain women to involve in “masculine” fields, such as politics.

The traditional gender socialization is based on patriarchal perspectives that put men’s position higher than women’s. Currently, in some countries, the traditional perspective of gender socialization still operates while, in another part of the world, it has started to change. Indonesia is one of the countries that experience the change in the perspective of gender socialization.

The accommodation of women’s participation in Indonesian politics has existed since decades ago. Even, it already existed before the establishment of Indonesia. However, S.G. Davies (2005) states that since the Suharto’s government took over the country in the mid-1960s, women’s political participation was circumscribed. But, the policy started to change again in the mid-1990s when the government signed the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action that give women full access to politics and decision-making.

The signing of the Declaration as well as the growth of the political turbulence in Suharto’s government in the mid-1990s gave way to women to speak and to criticize the government’s policies over women. After the democratization in the latest 1990s, the political participation of women and the discourse about it improved significantly. The wide spread of the new discourse has an impact on how the society sees the role of women in public. Consequently, the gender socialization in Indonesia changed as well.

These dynamics and the long experiences of women’s political participation, thus, made the current Indonesian society is more welcome to the bigger roles of women in politics, including in foreign policy. This improvement can be seen from the increasing number of women in Indonesian politics. For example, the increasing number of women in parliament. In the period of 1999-2004, the number of women was only 8.6% (BBC, 2011) while in the period of 2014-2019 is 17.32% (Katadata, 2017). Then, in 2001-2004, Indonesia had its first female president.

At the same time, the public acceptance of women in foreign policy materializes in three aspects. Firstly, the public reception of the appointment of Retno Marsudi as the first female ministry of foreign affair. Secondly, in the past ten years, the number of women who want to join the Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs has increased. This indicates that the involvement of women in the foreign policy field is acceptable among Indonesian society.

Thirdly, there is an increasing number of the accepted female applicants in the recruitment of Indonesian diplomats. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that, since 2005, it has accepted more women than men in its recruitment (BeritaSatu, 2015). Decades ago, the accepted female applicants only consisted of less than 20% compared to the male but, these days, the acceptance of female diplomats, in a batch, has increased to more than 50% (Jakarta Globe, 2018; Antaranews, 2008).

To accommodate the changes of gender socialization and awareness, Indonesian MOFA set up a working group on gender mainstreaming in 2006 that has two duties: to review all the MOFA’s regulations that are not compatible with gender principles, and to socialize gender principles in the MOFA and Indonesian representatives abroad (Secretary-General of Indonesian MOFA, 2006).

Problems Remain

Even though, there are improvements of gender socialization and awareness, some gender problems still remain in Indonesian foreign policy field. Firstly, while there are institutional improvements in Indonesian MOFA to support gender-based foreign policy as well as the growing number of female diplomats, cultural barrier still exists. The patriarchal norms and values are still the biggest obstacles for women to develop their diplomatic career. The perception of male superiority has forced the female diplomats to sacrifice their career and to deal with the problem of “to balance the family and jobs”.

For example, in the past, diplomatic couples were prohibited to be posted overseas at the same time but, now, the regulation has changed. The government gives freedom to the diplomatic couples to choose either to accept the diplomatic assignments abroad or to take on leave and accompany their spouses. However, in many cases the female diplomats that have to give up their posts to accompany their husbands because of cultural factors.

In another case, the female diplomats have to compromise with or, in some cases, to sacrifice their overseas posts because their male spouses, who are not diplomats, are unwilling to leave their job and to accompany their wives overseas. The cause of it is, again, the culture of male superiority.

Consequently, although since 2004 the ratio of the accepted female and male diplomats in the recruitment shows equal proportion, the number of women leading Indonesia’s foreign representatives is still small. For example, there are only 6 foreign representatives led by female diplomats (Tabloid Diplomasi, 2009). And, female diplomats only consist of 30% of all Indonesian diplomats in 2017 (Jakarta Globe, 2018).

Secondly, the new gender-based development in the executive branch (Indonesian MOFA) is not followed by the same improvement in the legislative. Indonesian parliament is still lack of the appropriate number of female representatives in the issues of international affairs as well as the number of female members of parliament who understand the international affairs issues.

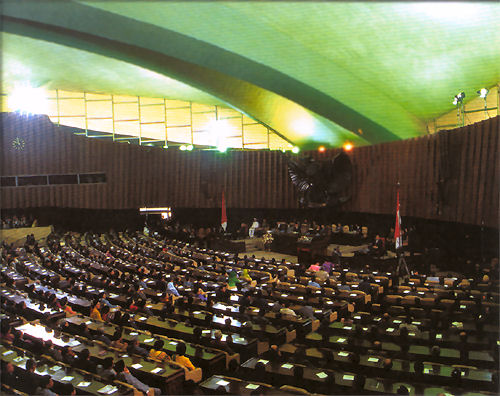

Indonesian legislative body (the People’s Representative Council, DPR) consists of 11 eleven commissions that have their own areas of responsibility. The Commission I is the one that is responsible for defense, intelligence, foreign affairs, and information. Currently, the Commission I has 52 members with only 5 of them are female (DPR’s official website). The number of the current female members of the Commission I is less than the last period (2009-2014) that had 7 female members out of 47 members. It is because the decline of the total number of female legislative in the current period (Kompas, 2014).

At the same time, the Indonesian parliament is also lack of the female members who have proper understanding of international affairs. It can be seen from the discussions on international affairs in the parliament, especially in the Commission I, that are dominated by the male members. Another example, the female members of Commission I almost never issue statements on international issues. Even, statements on those that are big issues for Indonesia, such as Indonesian migrant workers and Middle Eastern conflicts.

The cultural barriers, namely patriarchal norms and values, still trammel women’s eagerness to understand issues on international affairs because the perception of international affairs as toys for men. Consequently, when they were elected as the members of parliament they came to the House without proper understanding of international affairs. Another factor is the political parties’ internal decisions-making mechanism. The political elites of the parties have big influence on the appointment of the members of legislative commissions. It causes the appointment of the members of the commissions is not based on competency, but political reasons.

Besides, the regulations of affirmative action, that demands 30% of female representation in the parliament, has dragged political parties into pragmatic recruitment of female candidates. The selection of the female candidates is loosely based on competency, including the understanding on international affairs.

Moreover, the application of zipper system in Indonesian election, to improve the number of women to be elected in parliament, cannot assure the elected female representatives to have gender sensitiveness (Amalia, 2012). This condition, then, worsens the situation: the female members of parliament are lack of knowledge and understanding on gender-based international relations.

Conclusion

To conclude, the shift of the gender socialization in Indonesia has changed the way the Indonesian society sees the role of women in politics, including the role of women in foreign policy. The change has made some institutional improvements in the government, especially gender equality in the Indonesian MOFA.

However, the implementations of gender awareness and equality in the Indonesian MOFA still face some cultural barriers. At the same time, the improvement of the gender awareness and equality that are related to foreign policy field in Indonesian parliament is still none. This situation indicates that Indonesia needs bigger effort to promote and to push gender-based reform in the Indonesian foreign policy areas.

Wendy A. Prajuli & Richa V. Yustikaningrum

Wendy A. Prajuli is a lecturer at the Department of International Relations, Bina Nusantara University, Jakarta, Indonesia. His research interests are about security dynamics in Asia-Pacific, and foreign policy analysis.

Richa V. Yustikaningrum is a lecturer at the Department of International Relations, Bina Nusantara University, Jakarta, Indonesia. Her research interests cover gender relations in international relations as well as in Indonesian society and politics.

political parties must choose both men and women selectively to be seated in the Representative Council. Beside of Retno’s capability in settled Rohingya problem in Myanmar, her gender is fit to Aung San Su Kyi, settling thing with women talks.