In late summer 2019, during a conference trip, I visited the public park Marx-Engels-Forum located in the central Mitte district of Berlin, Germany. When I arrived at the wooded park by the bank of the Spree River, it was not Ludwig Engelhardt’s bronze sculptures of Marx and Engels that captured my attention. I gasped, rather, upon finding a picture of Indonesian women engraved on steel walls that surround the statues of Marx and Engels. The walls consist of reliefs with scenes from global communist movements—many of them portraying women. The Indonesian picture shows ten women in traditional Javanese kebaya attire and konde (hair bun), three of them sitting down with a sign in the middle depicting a hammer and sickle as well as the writing “P.K.I.” (Partai Komunis Indonesia or the Communist Party of Indonesia) and “S.R.” (Sarekat Ra’jat or the People’s Union). This sign provides a clue that the picture was taken during the heyday of the pergerakan merah (Red Movement) that organized the first popular and radical anticolonial mobilization in colonial Indonesia in the 1920s. However, the contrast between the historiography of the period and the steel relief was striking. That is, even though the Forum—constructed in 1986—vividly chose women to represent the Red Movement, it is very curious that the historiography of the Red Movement continued to be void of women.

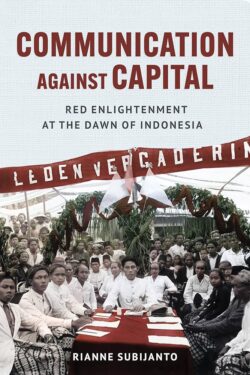

My recent book, Communication against Capital: Red Enlightenment at the Dawn of Indonesia, addresses this concern. It asks, if a radical movement was so popular, why did existing historiography of the period only tell its story from the lens of its male leaders (cf. McVey, 1965; Shiraishi, 1990)? What was the role of ordinary people in this popular movement? The book is aimed to unearth the active participation of ordinary people in the movement as well as to show the processes in which this participation occurred in the daily and ordinary setting of the people, over time, spreading beyond Java across the Indies and abroad. It reveals that the Red Movement led anticolonial resistance against Dutch rule by developing collective, nonviolent actions around new emerging communicative technologies and practices. The ten women in the picture in the Marx-Engels-Forum were a minuscule representation compared to the hundreds, and even thousands, of women who participated in the movement.

To be clear, the active participation of women in the Red Movement was not intended to create a women’s movement in a narrow sense. In other words, the communist women were not merely mobilizing in the movement for their own cause. Elaborating on Communication against Capital’s core insight, this article seeks to highlight the fact that, in the Red Movement, women did not just mobilize for the interest of the women’s branch. Rather, their involvement was evident throughout the movement including advocating for seemingly non-women’s issues. This is what I would argue the communist women’s largest contribution not only to the history of the Red Movement but also to the history of the women’s movement. What happened when women mobilized in a movement whose interests went beyond just women’s issues?

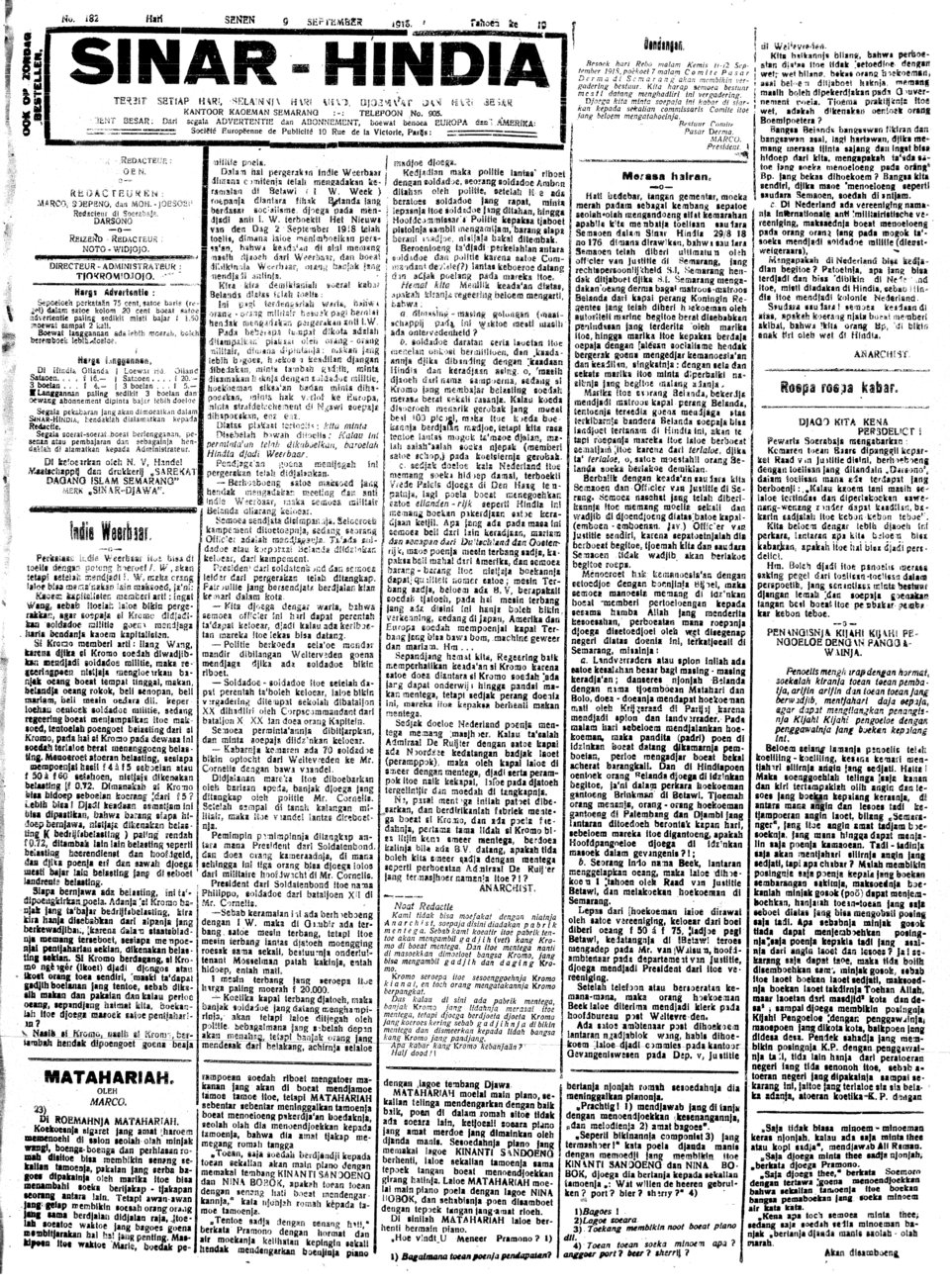

Before we answer that question, it is important to understand the nature of women’s involvement in the movement. Let’s understand this from the words of woro (Ms.) Djoeinah, the first female editor of Sinar Hindia newspaper. In her article “Beladjar Ta’ Mengasingkan Diri!” (Learning to Not Alienate Oneself!) in Sinar Hindia on 7 February, 1921, woro Djoeinah saw her authorship as a form of political participation. In her words, “Dengan hati merasa ta’ tetap, kami akan mengoeraikan kata-kata di dalam halaman S.H. itoe, toeroet berlomba-lomba dilapangan politiek” (with unsettled heart, we express words on the pages of S.H. [Sinar Hindia] to compete in the political field). The phrase “lapangan politiek” (political field) is key. Another unnamed author uses a different expression “medan politiek” to refer to the same meaning (D.T., 1921). For woro Djoeinah and those involved, the Red Movement was a political field and, hence, one’s involvement in it was an act of being political. The Red Movement united kromo (commoner) individuals in an archipelagic and global solidarity movement against colonialism and capitalism campaigning for human rights, justice, and freedom. Hence, inherent within the understanding of being political here is a struggle for material power for the kromo class to own and control their means of sustenance and production so that they could live a dignified life, which they had not been able to under aristocratic feudalism in Java and Dutch colonialism.

It must be made clear that kromo was a uniting collective identity of the people in the movement. Kromo means lower-class commoners without rank or status. The majority of them were illiterate, and they included a broad lower-class population of different backgrounds including peasants, workers, sailors, port workers, the urban poor, mothers, and housewives. Naturally, when the word “perempoean” (women) began to be used to name its branch, the label “perempoean kromo” quickly circulated and became the uniting identity of the women in the Red Movement.

Into what kind of praxes was “being political” translated? One of the key findings of Communication against Capital is that the Red Movement was the first anticolonial struggle in colonial Indonesia that was conducted not through warfare—as previous struggles were—but through the production of revolutionary communication. When women began to mobilize in the movement especially after the establishment of the women’s branch of “Sarekat Islam” (Islamic Union) called “Sarekat Islam Perempoean” (Women’s Islamic Union) in 1918, it attracted many who attended and organized openbare vergaderingen (public meetings). The participation of women became even more expanded especially after most (male) leaders were arrested and sent to exiles to remote islands or abroad following the strike in May 1923 led by the railway workers union VSTP. Between 1923-1925, women were prominent mobilizers who expanded the movement, making it popular and even more radical, leading meetings in various cities in houses, offices, schools, and cinemas across and outside of Java, including Sumatra and Maluku. These women chaired and spoke at rallies and meetings and talked about party building, strategies of mobilization, and communistic ideas. They also organized strikes in traditional markets (pasar) utilizing their power to control the distribution of goods and food. They knew fully well that if the sellers—mostly kromo women—stopped selling goods, upper-class people could not have access to their groceries. When some of the leaders were arrested following the VSTP strike, these women, too, organized donations to ensure that their families could survive. In the vergaderingen reports in Sinar Hindia, a donation drive was often held following public meetings in which women would donate money, food, and even jewelry to support their comrades. Women organized these public meetings in various places but among the most unique places was a public kitchen. The kitchen allowed more women to participate in political discussions and debates as they prepared food for their families.

Besides meetings, rallies, and strikes, communist women’s praxes also include writing, reading, and schooling. Many women, like woro Djoeinah, contributed their writing to revolutionary newspapers like Sinar Hindia. Like the topics discussed in public meetings, the topics of their writing were varied and did not merely discuss women’s issues, including colonialism, reactionary anticommunist groups, and revolutionary strategies. Equally, issues that are often seen as “women’s issues” such as divorce, polygamy, reproductive health, child rearing, and marriage were not just discussed by women; men too discussed these topics. In 1921, the communist politburo member Darsono, for example, released a three-part series of articles called “Kaoem Perempoean” (Women) discussing, among others, the difference between prijaji (upper-class) women and kromo women and the place of the latter in the Red Movement, expressing the sentiment of the kromo women in the movement. Alongside men, women developed and taught the communist school Sekolah Ra’jat (People’s School) that served many kromo children until it was banned following the revolt in 1926-1927. After the expulsion of Tan Malaka, founder of Sekolah Ra’jat, in 1922, these communist schools mushroomed across Java in Bantam, Buitenzorg, Batavia, Preanger, Cheribon, Pekalongan, Semarang, Madioen, Kediri, Bodjonegoro, Soerabaja, and Besoeki. In Sumatra’s Westkust, it was called the Thawalib School. Amidst this spread of these communist schools, Woro Djoeinah endeavored to build a special school for women where they taught each other skills and knowledge including reproductive health.

It should become clear now that the political field of perempoean kromo in the Red Movement did not center merely around perceived women’s interests, but they took upon them the larger interests of the Red Movement. In their speeches and writings, women’s oppression and exploitation were understood to be rooted in the intertwinement of patriarchy and capitalism in that overcoming capitalism was necessary to end these oppression and exploitation. Gender and sex, in this case, were perceived as class expression. Class here must be understood not as an occupation but rather as material power. Perempoean kromo did not have the material power to access a dignified life. Prostitution was a case in point, but also women’s access to education, health care, political rights, and equality in marriage. This is not to say that the women’s gender/sex interests became subsumed under the kromo class interests, but rather the class character for perempoean kromo was expressed, among others, through their gender/sex-specific experiences.

This interlocking understanding of class and gender/sex, in my view, is one of the key contributions of perempoean kromo. These women advocated for a more expanded understanding of the economy. For them, women’s struggle was not just about suffrage and access to political representation and governance, but it was also about nurturing the institutions often considered “non-economic” (non-value producing) that, in fact, directly contribute to the social and economic organization of the society, namely schools, education, the public sphere including literature and journalism, the market, health care, and political associations including unions. Women contributed to the movement by bringing to the center not just the questions of women’s representation in the movement but also the strategies to build and maintain the aforementioned social and economic organization in which “women’s issues” became extremely central. This understanding expressed 100 years ago by communist women in colonial Indonesia resonates with the thriving scholarship on social reproduction by contemporary Marxist feminists such as Tithi Bhattacharya, Susan Ferguson, Nancy Fraser, and Silvia Federici.

Let us now return to our question in the beginning of this article: how did women and “women’s interests” affect the Red Movement? Did the movement’s interest for the broader kromo class make women’s interests become secondary? Quite the reverse, the political participation of perempoean kromo in the movement, in fact, made women’s emancipation the demand of the movement at large, placing it as one of the core anticolonial and anticapitalist agendas. “Non-economic” and “informal” areas of social reproduction that were mundane and ordinary became important areas of struggle. Politics occurred not just in party meetings but also in cultural areas like marriage, health, fashion, child-naming, and childrearing. Likewise, as women, through their speeches and writings, demanded the movement’s class interests, it made the kromo demands universal. These demands did not just belong to the men or the elite leaders, but they became a shared expression of the movement’s collective demands as a whole. By standing in solidarity with men, not only did women help expand the Red Movement to include more diverse participants and issues, but they also made the movement to become more inclusive and universal. From the story of perempoean kromo we learn that, when women lead, they make the mundane and ordinary vital processes in movement building, potentially making the movement more democratic and egalitarian.

Rianne Subijanto

Rianne Subijanto is Associate Professor of Communication Studies at Baruch College, The City University of New York. She is the author of Communication against Capital: Red Enlightenment at the Dawn of Indonesia (Cornell UP, 2025).

References

D.T., 1921. “Terhadap Kaoem Poeteri Terpeladjar” (To the Educated Women). In Sinar Hindia, February 16.

McVey, Ruth Thomas. 1965. The Rise of Indonesian Communism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Shiraishi, Takashi. 1990. An Age in Motion: Popular Radicalism in Java, 1912-1926. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.