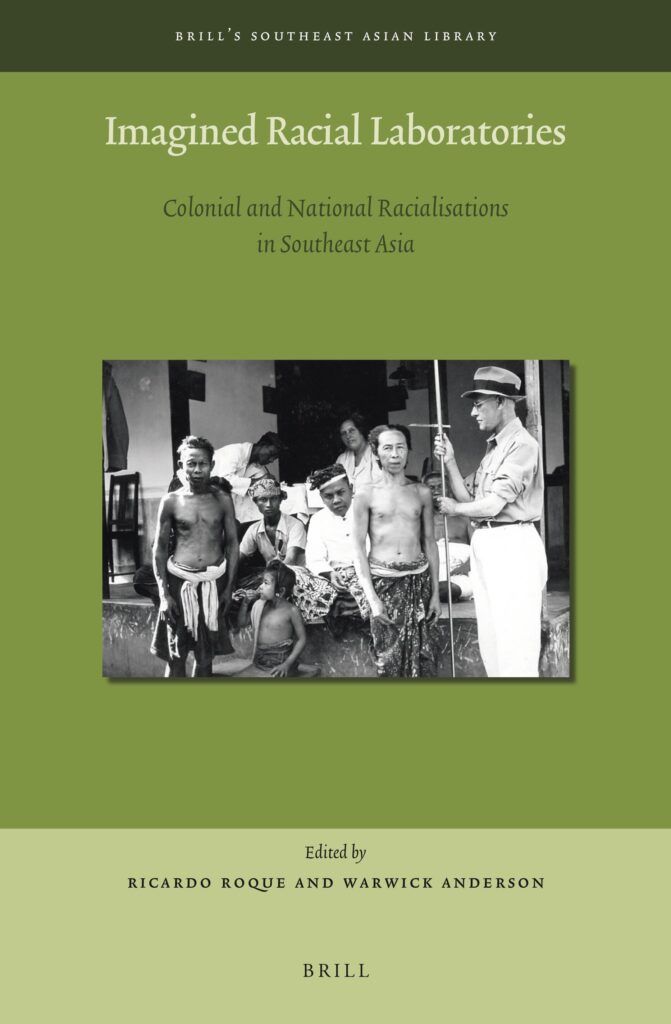

Title: Imagined Racial Laboratories: Colonial and National Racialisations in Southeast Asia

Author: Ricardo Roque and Warwick Anderson (eds.)

Publisher: Leiden: Brill, 2023, ISBN 978-90-04-54294-5

This edited volume shifts scholarly focus away from hackneyed notions of imagined communities and toward the fabrication of racial laboratories that placed Southeast Asian peoples within finely grained evolutionary hierarchies. These gradations may have been exogenously imposed but were not static, undergoing various modifications by indigenous agents incorporating aspects of racialization that served specific political and material agendas. Such elite-driven processes generally placed wealthy ruling classes at the ‘civilized’ end of the spectrum while consigning pagan peoples inhabiting ungoverned peripheries to the opposite extreme. Illegibility brought forth accusations of barbarism, albeit not always as an irredeemable state of being.

Authors concentrating on the Philippine case reaffirm established arguments that indigenous elites imbibed American colonial beliefs that ‘wild tribes’ outside the nascent nation’s geo-body had to be incorporated via protracted tutelage. Christian lowland rulers claimed such instruction was best conveyed by Filipinos themselves and American colonial officials had no right to keep ‘pagan’ tribes condoned off from a coalescing nation-state. Colonial rule stymied the formation of a national community that could only form with a reduction in foreign influence.

Gealogo’s chapter on Bilibid is a fascinating examination of how racialization took place within the confines of a colonial prison. The incarceration of various ethno-linguistic groups from across the archipelago may have generated solidarities from common experiences and hardships, but from the colonizers’ perspective it was an ideal forum in which to cultivate divisions. How effective this was from the perspective of those subjected to it is less clear. In addition, there is by now a substantial literature on how Philippine minorities actively embraced and advertised their sense of difference to American officials outside coercive institutions to keep land-grabbing Christian majorities at bay. More nuance would have refined this chapter’s arguments.

Roque’s examination of Portuguese Timor stands out as a more original contribution. Colonial efforts at inscribing Timorese peoples into a civilizational middle ground between Malay and Melanesian worlds is highly engaging. Twentieth century anticolonial leaders combatting Indonesian military occupation chose to tilt cultural affiliations away from Malay-based cultures and toward Papuan peoples. Thus, racial demarcations were modified and reconfigured to solidify a culture of difference. Along a similar vein, Sysling’s look at Bali and Lombok demonstrates how indigenes deployed colonial-era anatomical measurements as markers of difference that confirmed cultural distinctions and separate racial categorizations which factored into majority/minority struggles for preferential access to scarce resources.

The one major shortcoming of this volume is its overconcentrated focus on insular Southeast Asia. Only Hoskins chapter deals with Vietnam. Rather than bringing balance, it appears somewhat misplaced. The deep ethnic complexities of Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and Myanmar remain beyond this study’s reach and consequently limit its utility for those seeking a comprehensive regional survey. Scholars of island Southeast Asia, by contrast, will find much of value in it.

Mesrob Vartavarian

University of California, San Diego