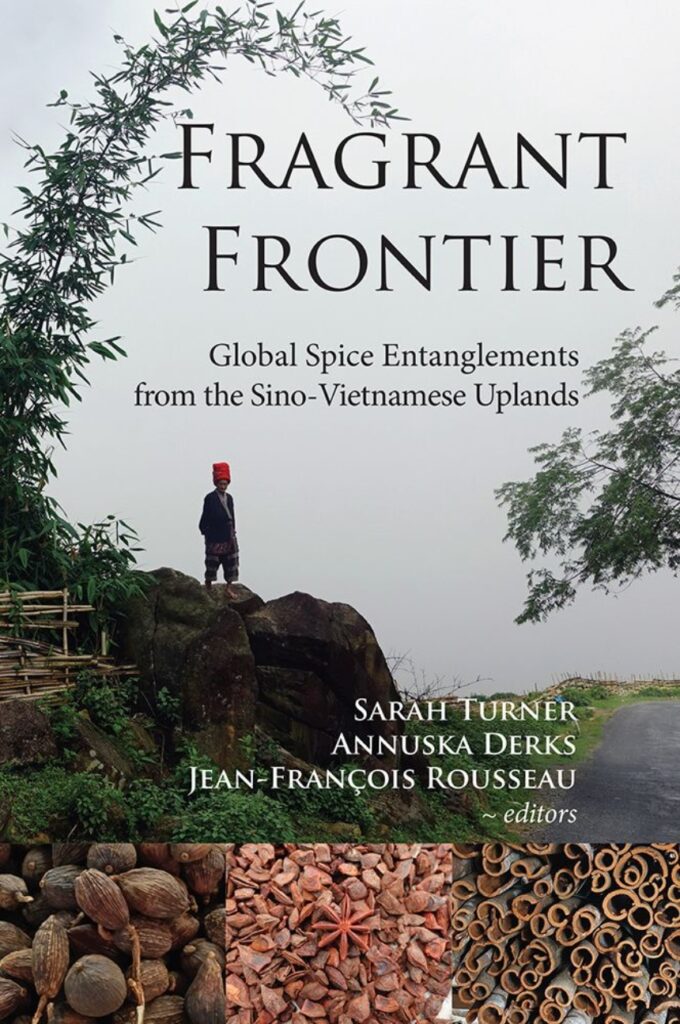

Title: Fragrant Frontier: Global Spice Entanglements from the Sino-Vietnamese Uplands

Authors: Sarah Turner, Annuska Derks, and Jean-François Rousseau (Eds.)

Publisher: Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies, 2022

Mention the topic of spices in Southeast Asia and I suspect that most people will think of the Maluku Islands of eastern Indonesia, the main source in the world of such spices as nutmeg and cloves. However, there is another area in the region that is also a significant producer of certain spices, namely the Sino-Vietnamese border region where farmers produce large quantities of black cardamom, star anise, and cinnamon for the global market. In the edited volume Fragrant Frontier: Global Spice Entanglements from the Sino-Vietnamese Uplands, editors Sarah Turner, Annuska Derks, Jean-François Rousseau introduce readers to this mainland version of the “Spice Islands” of Maluku, an area that they call the “Fragrant Frontier.”

The volume consists of eight chapters and an afterword, with some chapters dealing with spice production in Vietnam, and others with China. The book begins with an opening chapter by the editors that addresses conceptual and contextual issues. The second chapter then embarks on an examination of star anise production. Entitled “Vietnam’s Star Anise Commodity Chains Entangled in Flex-Crop Debates,” in this chapter authors Sarah Turner and Annuska Derks explore the trade routes that connect cultivators in northern Vietnam to consumers worldwide. They examine the socio-economic, cultural, and political links between the various nodes in this network and demonstrate how the livelihood of ethnic minority cultivators can be affected by the decisions of distant actors. In particular, the authors discuss how in addition to such factors as unpredictable harvests, other more distant factors such as fluctuating demand, and fragmented knowledge along the commodity chains also impact the lives of upland ethnic minority farmers.

In Chapter 3, “Cardamom Cultivator Concerns and State Missteps in Vietnam’s Northern Uplands,” Patrick Slack moves on to look at black cardamom and examines the lives of farmers producing that spice in the Bát Xát district of Lào Cai province. Here he finds that these farmers work to maintain their livelihoods in the face of multiple pressures. First, there are various initiatives that the government has implemented in an effort to bring about an agricultural transformation. This includes halting swidden agriculture, increasing mono-crop production and reforesting certain areas of the province. Black cardamom farmers have both adopted and adapted to these policies, but have additionally encountered severe weather events, such as droughts and cold weather precipitation.

Cinnamon is then the subject of Chapter 4, “The Taste of Cinnamon: Making a Specialty Produce in Northern Vietnam” by Annushka Derks, Sarah Turner, and Ngô Thúy Hạnh. Cinnamon is derived from the bark of evergreen trees from the genus Cinnamomum. Within that genus, there are different species, such as cassia, the bark of which can also be used as a spice. However, cinnamon is considered of higher value. Vietnamese cinnamon should therefore be able to gain a high-end global market, however, as the authors document, there are various changes that take place along the commodity chain which make it difficult for that value to be preserved. For instance, much of the cinnamon that is produced in Vietnam gets exported to China where it is mixed with lower-grade cassia and is sold as generic cinnamon.

With Chapter 5, the examination of the production of spices along the Sino-Vietnamese frontier moves to China as François Rousseau and Xu Yiqiang look at “Extreme Weather Events, Cardamom Livelihoods, and Commodity Chain Dynamics in Southwest China.” In 2016 and 2017, the authors attempted to examine an area in Yunnan province that produces cardamom but had their planned researched disrupted by extreme weather events. They then decide to examine the effects of extreme weather on the cardamom commodity chains and the various stakeholders along those chains. What they found is that the commodity chains are often held together by informal arrangements and that information does not spread equally through these networks, leading to different levels of vulnerability. For instance, some stakeholders have access to market information and are able to adapt accordingly, while others lack such information.

In Chapter 6, “False Promises: Cardamom, Cinnamon, and Star Anise Boom-bust Cycles in Yunnan, China,” Jennifer C. Langill and Zuo Zhenting likewise shed light on the vulnerability of spice farmers in China by examining how smallholder farmers in Yunnan province have fared as the demand for their crops has gone through boom-bust cycles. They do this through a comparative examination of the production of black cardamom, cinnamon, and star anise. Each of these spices has gone through such a cycle, and at the bust point, some smallholder farmers have diversified their activities while many have moved away from spice production. Meanwhile, government support during these times of instability has often been lacking.

Chapter 7 moves back to Vietnam, as authors Michelle Kee and Celia Zuberec look at “Marketing Makeovers and Mismatches of Vietnam’s Quintessential Spices.” Focusing again on all three spices, the authors examine how cinnamon, black cardamom, and star anise are marketed. They do this by interviewing state officials in Vietnam and examining information on websites operated by Vietnam-based exporting companies, and overseas importing and retail companies. What they find is that Vietnamese officials emphasize the fact that spices have obtained “geographical indications” (GIs), official signs on products that document their place of origin. However, the Vietnam-based exporting companies, as well as wholesalers in China, then present these spices in more generic terms as products that have been professionally and hygienically produced and that can be efficiently distributed to the global market. Finally, retailers in the US and Europe then promote these spices as the products of “exotic” ethnic minority cultivators. As such, once again we see ways in which the value of the spices is transformed along commodity chains.

The final full chapter of the book, “Reflections on Fragrant Frontier Entanglements,” by Sango Mahanty is a reflection on the preceding chapters. In particular, Mahanty discusses the volume’s contribution to borderland and frontier studies, as well as to the study of such topics as commodity chains, agrarian transitions, and the livelihoods of farmers. Here, Mahanty points out that spices are fascinating in that beyond the complex networks that connect their production and distribution are the equally complex ways in which the value of these spices is determined at various stages along the supply chains that lead to global markets. Finally, Mahanty also notes how this volume sheds light on the effects of state interventions (or at times lack thereof) into the areas where the spices are grown. This reflection is then followed by an afterword by Sarah Turner that examines, as of February 2022, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Sino-Vietnamese uplands and how cultivators were responding to changing conditions.

I read this book as a “lay person.” I am not an expert on any of the issues discussed in this volume, but instead, am an historian who has a general interest in the region that the authors examine. That said, I found Fragrant Frontier to be a fascinating read. The editors do a very good job of introducing to the reader the concepts and issues that are necessary for understanding this topic. Each chapter also covers any theoretical or methodological issues that are needed to comprehend the analysis in the chapter. Further, all of this is presented in a clear and engaging manner. Finally, the case studies are all much more complex and detailed than I have the space to discuss here. Taken together they provide a detailed overview of numerous aspects of spice production in the Sino-Vietnamese border region. And while many of the authors finish their chapters by indicating that there is a need for more research, this volume has already established a very solid foundation for anyone who wishes to do so.

Liam C. Kelley

Associate Professor of Southeast Asian Studies

Institute of Asian Studies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam