In May 1899, Kartini (1879-1904), writing in the colonized space of Java under the Dutch, wrote a passage on the powerful storm of change that was engulfing the world in which she lived:

“[T]he spirit of the age, my helper and protector, made his thundering steps heard; proud, strong, old institutions wobbled as he approached their territory–strongly barricaded doors sprang open, some as if of themselves, others with more difficulty, but open they did, and let in the unwelcome guest. And where he has been, he has left his tracks.” (“Letter to Stella Zeehandelaar”; Kartini, 1912).

Barely 20 years old when writing this, Kartini embraces unequivocally the turbulence of change as a helping, protecting spirit, whose destructive impact is necessary to enable her and her fellow countrymen and women to free themselves from colonial oppression and feudal complicity. Coming only 51 years after the appearance of the Manifesto of the Communist Party in 1848, Kartini’s personification of the turbulence of change echoes its opening statement:

“A spectre is haunting Europe–the spectre of communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre…” (Marx and Engels, 1847).

In her post-independence afterlife, Kartini has become a symbol of state “ibuism” (Suryakusuma, 1996), and, with the rise of the New Order under Soeharto, reinforces the patriarchal foundations of militarized authoritarianism. Her youthful exuberance is replaced by a passive icon of staid/state motherhood, despite the fact that she rebelled against marriage and, eventually having to submit to it, died at age 25, four days after giving birth to her only child. More important to our contemplation on turbulence, is the erasure of the strong progressive stance in her thinking and writing by colonial officials who were, supposedly, her “real” protectors. This silencing of her voice was eventually taken up once more by the New Order state.

Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s 1962 Panggil Aku Kartini Saja (“Just Call Me Kartini”) is one of the rare works underscoring Kartini’s left-leaning progressivism. However, his arbitrary thirteen-year imprisonment, the destruction of his library and unfinished manuscripts, and the wholesale banning of his writing under the decree of the Provisional People’s General Assembly of 1966 (TAP MPRS XXV/1966) banning all publications branded as promoting “Marxist/Leninist” ideology meant that all memories of this early expression of progressivism were violently suppressed, and largely remain so today.

During the Dutch East Indies, this type of turbulence was seen as a direct threat to colonial extractive strategies with the end of the state-controlled Cultivation System, the 1879 rise of the new Liberal Policy, and drive towards privatization. The state became a system to secure and police the “peace and order” (“rust en orde”) demanded by private capital. Understanding the silencing of Kartini reveals the collaboration of privatization and the rise of the “security approach” (pendekatan keamanan) police state that undergirds New Order and post-Reformasi Indonesia today. Turbulence as a spectre came to be co-opted by capitalism, and constantly invoked, in order to play its distorting role in the perpetuation of the liberal order of the colonial era, and the current neoliberal order.

Manufacturing Turbulence: “Malari” as a Point of Reflection

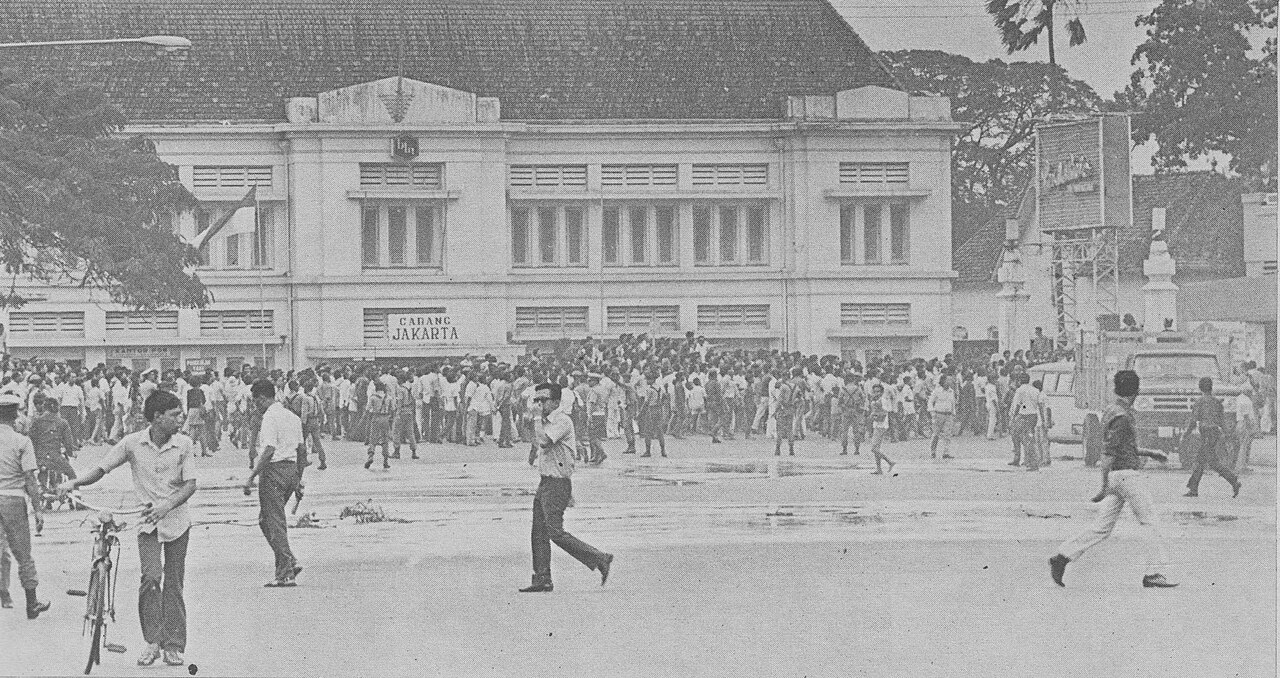

The Malapetaka Lima Belas Januari, or, more commonly, Malari, translates to the “Catastrophe of 15th January.” Occurring in 1973-1974, less than eight years after the violent rise of the New Order regime, it remains one of the more opaque events in contemporary Indonesian history.

Because of its multiple lacunae and occlusions, it resists a comfortable linear plot-line and urges a more critically engaged narrative. The linear plot, one which was much disseminated by the media and by the state, and subsequently by the judicial system itself, was that in anticipation of the state visit by Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka. Indonesian university students, protesting Japanese investment projects in Indonesia, rejected his visit, created enormous turbulence that spread beyond the campus, deliberately incited urban proletariat crowds, who rioted, destroying anything recognizable as being of Japanese manufacture (including Toyota automobiles assembled in Indonesia), and burning down the new market complex of Senen (pasar Senen) in downtown Jakarta. Student leaders were detained, interrogated, and many charged with subversion, especially Hariman Siregar, chair of the University of Indonesia’s Student Council, and the young scholar of economics, Sjahrir S.E. The early charges against campus activists were that they were aligned with the leftist wing of the PSI (Partai Sosialis Indonesia) – the defunct Socialist Party of Indonesia which, supposedly, masterminded the student protests in a bid to overturn the New Order government. Thus, caught up in the sweeps by the military and police were “Socialist” intellectuals like Sarbini Sumawinata and Soebadio Sastrosatomo, both of whom were imprisoned for more than two years without due process (Thee Kian Wie, 2007), along with numerous other intellectuals and human rights lawyers like Adnan Buyung Nasution and Haji Princen.

The descriptions of the phases of the interrogations are based on personal experience over several rounds of intensive questioning bolstered by comparisons with what others had undergone, as well as the trials of Hariman Siregar and Sjahrir S.E. During preliminary interrogation sessions at Military Police (POM) headquarters in Jakarta, many questions seemed designed to elicit answers showing evidence of a leftist PSI conspiracy, even trying to discover links to supposed secret communist networks. Activists who had not yet been apprehended went underground because of the fear this inspired.

However, during the subsequent interrogations conducted by the office of the State Prosecutor (Kejaksaan) a narrative template emerged that guided the second phase of investigation aimed at producing evidence and material witnesses for the trials. This template became the narrative picked up and circulated widely, serving as a template also for much journalism to this day.

When Elephants Fight, the Mousedeer Gets Trampled

At the prosecutorial interrogations, potential witnesses and persons of interest were handed a long questionnaire to be filled. In personal experience, although I avoided detention, prosecutors exerted different forms of pressure to try to force a set answer to the questions. This included being locked in an isolated room for hours, and threats of being imprisoned with Gerwani (Indonesian Women’s Movement aligned with the PKI, of whom many were arbitrarily rounded up, suffered rape and torture, and held for multiple years). When that did not produce the expected answers, prosecutors displayed a graph explaining the scenario for which the interrogations had to present the evidence.

This graph used a myth familiar to most Southeast Asians: two elephants fighting, while the tiny mousedeer (pelanduk) is the one that suffers the most. The two elephants represented different army factions: on the one hand those under head of State Security Command (Pangkopkamtib), General Sumitro Sastrodihardjo, the other consisting of a group of army generals directly loyal to Suharto, the ASPRI (personal assistants), with General Ali Murtopo as head, and in charge of special intelligence, thus challenging the intelligence under Sumitro’s Kopkamtib. The mousedeer represented students and intellectuals as victims caught in a struggle that was not of their own making.

Clearly, the performance plot had shifted away from the PSI and more clearly to the different army factions. Was this plot shift a maneuver by Suharto to gain more complete control over the army and intelligence? The ASPRI had been a target of campus criticism for its lack of transparency and its powers to accumulate funds from a variety of state and private sources. Ostensibly in response to the criticism, in late January 1974, Suharto disbanded it. Some of the student trials continued, but most of the campus activists and the intellectuals were never brought to trial. Nevertheless, a theme that came up during the trials was the deliberate provocation by the ASPRI who mobilized mobs to riot and burn the shopping centre at Senen, while blaming Hariman Siregar and university students for the action, even though the students had been many miles away from the centre when the riots broke out.

This type of secret army operations has been cleverly spoofed in Nano Riantiarno’s brilliant 1995 drama, Semar Gugat. But it also forms a template for the army’s manufacturing of turbulence through destructive riots, especially those of 1998, in attempts to derail the massive student and labor actions demanding that Suharto step down. (Direct evidence of palace interference in the trials was revealed to me by the wife of one of the judges at the trial of Sjahrir, who said that every morning before appearing in court, the judges were summoned to “Cendana” –Suharto’s residence–to be briefed by him.)

One question remains: why was the PSI edited out of the narrative of turbulence in the 1970s? We need to look at linkages around Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, Dean of University of Indonesia’s Faculty of Economics and founder of the group of technocrats who designed the neoliberal New Order Economic policy that eradicated Sukarno’s plan for the nationalization of foreign investment, with particular focus on colonial era plantation holdings.

An important figure in the PSI, he became embroiled in the PRRI movement to break away from Sukarno, and sought exile abroad. After Sukarno’s fall, he returned in 1967 to become the power behind the economic policies of the New Order (Nasution, 1992; Subiyantoro, 2006). The first law promulgated by the Provisional General Assembly, the highest power in the land, cleansed of the PKI, was Act No. 1, 1967, on Foreign Investment, which dismantled Sukarno’s policy towards a national economy–supported by the PKI–and opened Indonesia to direct foreign investment. While Japan was one of the first to take advantage of this opening, that country was a proxy for wholesale capitalist exploitation of Indonesian natural and human resources. Waiting in the wings was Freeport McMoran, one of the first foreign companies to gain rights to exploitation of the copper and gold deposits in West Papua (Poulgrain, 1998).

The consolidation of the military, in combination with neoliberal policies by co-opting and distorting the spirit of the storm that inspired Kartini has remained as a basic template for what passes for governance in Indonesia, and continues, with the ascendancy of General (retired) Prabowo Subianto–son of Sumitro Djojohadikusumo–the expansion and securitization of mega-investment projects, and the reinstatement of the Indonesian military in direct and indirect interventions in government ushered in by the revision of the 2004 laws on the Indonesian Military passed by Parliament, March 20, 2025, characterized by protesting students and intellectuals as returning the dual function of the military (Tempo.co. 2025).

For historians, Walter Benjamin’s (1969) figure of the angel of history (Angelus Novus) has become a trope to contemplate the paradoxical connectedness of catastrophe and progress. The image of the backward-facing angel, propelled by powerful winds of change, seeing only the destruction left in their wake, signals both the horror and the hope of modernity on the brink of war. In this image, the storm or turbulence seems to lead to an impossible impasse.

Despite the apparent helplessness of the angel, Benjamin sees hope in what he terms “purposive remembering” as action against the forces that push towards forgetfulness. This brief essay has been an act of purposive remembering: to encounter hope in the act of recovering Kartini’s full voice and embrace of the transformative power of turbulence.

Sylvia Tiwon

Sylvia Tiwon is Chair and Associate Professor of Southeast Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. She obtained her Ph.D. in South and Southeast Asian Studies from the University of California, Berkeley. Before earning her doctoral degree, she graduated in English from Stanford University and the University of Indonesia. Her interests lie in the interplay of social, political, and literary dynamics, focusing on orality, literacy, and gender studies. Her major publications include Breaking the Spell: Colonialism and Literary Renaissance (1999) and Trajectories of Memory: Excavating the Past in Indonesia, co-edited with Melani Budianta (2023). Her current project focuses on race, literary aesthetics, and abducted subjectivities in Indonesia.

References –

Benjamin, Walter. 1969. Illuminations. New York: Schocken Books.

Kartini, R.A. 1912. Door Duisternis Tot Licht. ‘S Gravenhave: Luctor et Emergo.

Nasution, Adnan Buyung, 1992. The Aspiration for Constitutional Government in Indonesia. Jakarta: Pustaka Sinar Harapan.

Poulgrain, Greg. 1998. The Genesis of Konfrontasi. London: C. Hurst.

Riantiarno, N. 1995. Semar Gugat. Yogyakarta: Yayasan Bentang Budaya.

Subiyantoro, Bambang, ed. 2006. Negara Adalah Kita. Jakarta: Prakarsa Rakyat.

Suryakusuma, Julia. 1996. “State and Sexuality in New Order Indonesia.” dalam Laurie Sears, ed. Fantasizing the Feminine. Durham: Duke University Press.

Tempo.co. 2025, https://www.tempo.co/cekfakta/keliru-klaim-bahwa-revisi-uu-tni-tidak-mengembalikan-dwifungsi-abri-1225197

Thee Kian Wie, 2007. “In Memoriam Professor Sarbini Sumawinata, 1918-2007.” Economics and Finance in Indonesia, Vol 55 (1).

Toer, Pramoedya Ananta. 1997. Panggil Aku Kartini Saja. Jakarta: Hasta Mitra.