“The entry of the Left into the municipal council can be considered a success. Comrades Dekker, Wiwoho, Malaka (Tan?), and Soekindar, all of whom stood with the people (Ra’jat), have managed to secure membership in the council. This will undoubtedly strengthen the position of the Left within the gemeenteraad. It is an important development for the municipality of Semarang, for this change in council composition may finally bring attention to the degrading conditions and unjust regulations affecting the city’s kampongs. Our gemeenteraad, which until now could hardly be described as a space for the voices of the people, is now hoped to become a council that does not neglect the interests of the lower classes.” (Soeara-Ra’jat, 16 October 1921)

The story reported in Soeara Ra’jat (the Indonesian Communist Party’s biweekly bulletin) on 16 October 1921 constituted a moment of quiet but consequential transformation in the political life of the colonial city in the 1920s. Far from being confined to the episodic drama of strikes and insurrections, as conventional accounts might suggest, the Indonesian Left was deeply enmeshed in the quotidian structures of municipal governance. The significance of this moment lies less in its immediate legislative outcomes than in its symbolic and institutional implications. The Left’s municipal platform—anchored in demands for universal suffrage, the dismantling of racially inflected administrative structures like the kapitan system (the colonial indirect rule via ethnic intermediaries in segregated communities) and investments in housing and public health—outlined a vision of progressive urban citizenship rooted in everyday material concerns.

This was a politics attentive to the infrastructures of urban inequality, but one that operated within, rather than wholly against, the formal machinery of colonial rule. What emerges from this episode is a more nuanced understanding of Indonesia’s political modernity. The municipal council became, in effect, a contested terrain in which competing imaginaries of the colonial city were staged. This “practical politics” provided the left with a wider platform to forge alliances and lay the groundwork for a broader socialist political project in the Dutch’s colonial city at the time. Here, the Left did not merely oppose imperial authority; it sought to inhabit and reconfigure it from within. By drawing on the case of early twentieth-century Surabaya, this article revisits the history of the Indonesian Left by foregrounding the city as the material foundation for the emergence of a progressive political practice.[1]

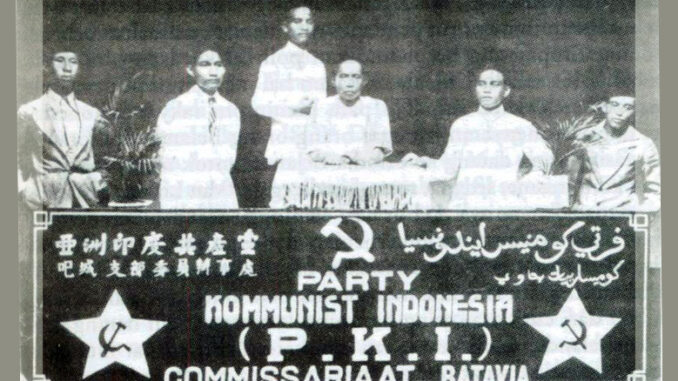

Source: “De Eerste Marxisten in Indonesië”, De Waarheid, 1989.

Contested (Colonial) Urban Governance

By the final decades of the nineteenth century, Surabaya had been remade by the circuits of imperial capital and the infrastructures of empire. The opening of the Suez Canal (1869) and the Dutch Liberal Policy (1870) catalyzed a transformation that saw the city evolve from a modest garrison town into a bustling node in the global economy. Ports, railway lines, and warehouses recast its physical landscape, while European capital and migration redefined its social hierarchies. The demographic shift was marked: the European population more than doubled between 1870 and 1890, a numerical reflection of the tightening grip of colonial capitalism.

This metamorphosis produced not only economic growth but also a new urban social stratum—the orang particulier sadja, or middle-class Europeans unaffiliated with the colonial bureaucracy. As doctors, engineers, journalists, and private clerks, they became the custodians of a civic public sphere, advancing claims to urban modernity through associational life, press culture, and reformist politics. Yet their emergence was shadowed by a growing antagonism with the ambtenaren, the colonial state’s officialdom, whose authority was increasingly viewed as antithetical to the city’s progress. Liberal voices like Adriaan Paets tot Gonsayen, a successful lawyer and a member of Surabaya city council, decried the Indies bureaucracy as an inert apparatus, more interested in preserving procedures than addressing urban dysfunction.

Out of this antagonism emerged a push for municipal reform. The gemeente, an administrative unit similar to a city or town council, and gemeenteraad, an elected body that governs a municipality, were envisioned as liberal democratic institutions capable of embodying civic representation. The 1903 Decentralisatie Wet offered partial vindication, and in 1906, Surabaya’s municipal council was formally constituted. But its structure reflected colonial compromise more than liberal triumph. Of fifteen European seats, eight remained under bureaucratic control; six more were appointed to non-European elites, ensuring multiracial representation without democratic parity. This was decentralization without full enfranchisement—a calculated concession to maintain imperial hegemony.

Nevertheless, the gemeenteraad functioned as an experimental space where different visions of urban authority clashed and coalesced. Debates over infrastructure, sanitation, and land use exposed not only class tensions but competing racialized claims to urban belonging. The city thus became more than a site of economic accumulation; it was a crucible in which the contours of colonial citizenship, public authority, and social justice were forged. In Surabaya’s political ferment, one discerns the early stirrings of an urban modernity both shaped by and resistant to the structures of empire.

Socialist Urban Politics

The entry of socialist actors into municipal politics in the Dutch East Indies reflected a conscious recalibration of political strategy in the face of colonial constraints. Far from confining themselves to agitation or revolutionary polemic, early members of the Indische Sociaal-Democratische Vereeniging (ISDV) recognized the gemeenteraad as a critical institutional arena for contesting urban modernity. Figures such as Westerveld, who sat on the Semarang city council, articulated a vision of urban governance that challenged the hegemony of capital and speculative land ownership. Drawing on European social-democratic traditions, Westerveld advocated for municipal acquisition of residential land—not for profit, but for redistribution—establishing the conceptual groundwork for publicly subsidized housing within a colonial context.

In Surabaya, this vision took shape with greater institutional force. Following the establishment of the municipal council in 1906, L.D.J. Reeser and Mr. van Ravensteyn sought to broaden the terrain of political participation beyond the European commercial elite. Acting as chair and secretary of the Verkiezingscomité, they initiated efforts to involve women (albeit symbolically) and encouraged the Native, Chinese, and Arab residents to participate in civic discourse. While ultimately unsuccessful in early electoral contests—defeated by conservative industrialists—their attempt to pluralize urban representation prefigured later alliances that would yield more tangible outcomes.

Source: Preanger Bode, May 17, 1916.

The ISDV’s adoption of “practical politics” in 1914, under Henk Sneevliet’s leadership, marked a turning point. Rejecting abstract ideological purism, the party sought to contest power from within the very institutions of the colonial state. In Surabaya, this shift culminated in an alliance with the nationalist organization Insulinde. Their joint platform, Sociale Gemeentepolitiek, advanced a dual agenda: extending the franchise to educated Indigenous citizens and asserting public control over strategic urban land (gemeentegrond). These demands not only disrupted the racial logic of colonial representation but foregrounded the question of material redistribution within an unevenly developed urban economy.

The coalition’s electoral victory in the 1914 city council elections—defeating established liberal and Christian-ethical parties—was both symbolic and substantive. Surabaya became the only city in the Indies with a formally recognized socialist faction in its municipal governance. While limited in numbers, the faction succeeded in institutionalizing a new discourse of urban rights—linking suffrage, housing, and land to the broader project of social justice.

In this sense, the gemeenteraad, this essay suggests, functioned not merely as a colonial bureaucracy but as a contested site where socialist ideas of citizenship and governance were translated into practice. Yet the fragility of this experiment was evident. A parallel attempt in Semarang failed due to the demographic limitations of the Indigenous electorate. Still, the Surabaya case underscores the capacity of leftist politics to infiltrate and reshape colonial institutional life—offering a glimpse of a political modernity that emerged not in defiance of empire, but through its interstices.

The Left and the Crises

Between 1916 and 1919, Surabaya emerged as a laboratory of leftist municipal intervention within the limits of colonial governance. Confronted by the dislocations of the First World War—rising prices, disrupted supply chains, and an acute housing shortage—the socialist faction in the city council, led by C. Hartogh and backed by the ISDV–Insulinde alliance, repositioned the gemeenteraad as a site of progressive experimentation. The dual imperatives of housing reform and market regulation animated their agenda. Hartogh spearheaded the creation of the Woningbedrijf and Grondbedrijf—municipal entities tasked with constructing affordable housing and regulating land speculation. Cross-party cooperation followed, with the formation of the Woningvereeniging alongside Jos M. Suijs (Christian Ethical Party) and D. Williams (Insulinde), signaling a pragmatic coalition politics rooted in social need rather than ideological purity.

Yet this experiment was hemmed in by colonial racial hierarchies. Though formally enacted with funding from Java Bank loans and municipal bonds, the housing scheme disproportionately favored low-income Indo-Europeans. Indigenous laborers, despite being the city’s urban majority, remained structurally excluded—highlighting the limitations of redistributive reform within a segregated civic order.

The wartime crisis also foregrounded another dimension of municipal activism: food security. In early 1918, Hartogh introduced a motion to impose price ceilings on essential goods. The government responded with public kitchens and rice subsidies, but price manipulation by Chinese merchant syndicates—revealed through official inquiries—underscored the vulnerabilities of a racially segmented urban economy. Here, leftist politics began to extend beyond European constituencies. In 1919, Hartogh collaborated with Rosenquist (Sarekat Hindia) and Soekiran (Sarekat Islam) to demand oversight of rice distribution. A mass rally led by Muso of Sarekat Islam soon followed, signaling the beginnings of a fragile but significant interethnic political convergence.

This episode marked a rare moment of alignment between European socialist actors and Indigenous mass organizations. Yet the racial architecture of colonial electoral politics quickly reasserted its authority. Despite growing support, Hartogh narrowly lost the 1918 election after ISDV severed its alliance with Insulinde and sought accommodation with Sarekat Islam. Indigenous voters—who constituted the majority of Surabaya’s population—were allocated only 78 votes. Electoral power remained concentrated in the hands of Europeans and Indo-Europeans, many of whom remained wary of socialist agendas.

The left’s municipal experiment, while bold in vision and method, remained circumscribed by colonial structures that defined the boundaries of political legitimacy and urban belonging. Still, it revealed a counter-narrative to dominant accounts of colonial politics: one in which the city became a contested arena for imagining more equitable futures—not through insurrection, but through council motions, public alliances, and the slow work of civic transformation.

Conclusion

Prevailing accounts of Indonesia’s nationalist movement have tended to privilege elite narratives, marginalizing the formative interventions of the political Left in shaping the contours of urban politics. Early socialist and communist actors, typically recalled in the context of radicalism or repression, were in fact embedded in the quotidian life of the colonial city. In locales like Surabaya, leftist activists entered municipal institutions and articulated a program rooted in the lived realities of urban inequality—housing shortages, land control, and access to food. These were not merely technocratic concerns but signposts of a deeper political project: the assertion of urban citizenship within a racially stratified colonial order.

Surabaya thus emerges as a critical site where ideology was operationalized through practical engagement. The municipal council, far from being a peripheral space, became an arena where socialist actors contested exclusionary urban governance and sought to reimagine the city as a domain of shared political belonging. Their efforts exposed the fault lines of colonial modernity and anticipated a politics that was both redistributive and inclusive. That this chapter remains largely absent from mainstream historiography speaks to the persistent marginalization of non-elite political visions. Revisiting the Surabaya Left compels us to recognize how democratic ideals and inclusive politics can begin at the level of streets, neighborhoods, and day-to-day situation of ordinary people. In light of today’s urban challenges in Indonesia, the legacy of this early leftist politics offers both a warning and an inspiration: that the city must remain a space not merely for capital and control, but for justice, representation, and collective belonging.

Andi Achdian

Andi Achdian is a historian and curator whose work explores the intersections of urban history, anti-colonial politics, and public memory in Southeast Asia. His research focuses on the social and political transformation of colonial cities, with particular attention to Surabaya in the early twentieth century. He chairs the Sociology Program at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Nasional, Jakarta. He is the author of Race, Class, and Nation: The History of the Anti-Colonial Movement in Surabaya (Marjin Kiri, 2021). In addition to academic works, he has curated several historical and human rights exhibitions, including the Munir Human Rights Museum (2013) and the Comarca Balide Museum in Timor-Leste (2024).

[1] The narrative presented here is based on the author’s recent book. See Andi Achdian (2023). Ras, Kelas Bangsa: politik pergerakan antikolonial di Surabaya abad ke-20 [Race, Class, and Nation: The History of the Anti-Colonial Movement in Surabaya]. Jakarta, Marjin Kiri.