Japan can be said to be the pioneer in institutionalizing the concept of “economic security.” It established a ministerial office on economic security in 2021, enacted the Economic Security Promotion Act (ESPA) in 2022, created a Trade and Economic Security Bureau in Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) in 2024, and set up a division on economic security in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) last year. Although as early as 2018, the first Trump Administration had already classified “economic security” as “national security”, underscoring economic power as a vital instrument of a country’s Comprehensive National Power (CNP).

The ESPA, which is Japan’s principal framework for economic security, has four pillars: supply chain resilience, public-private partnership on research and development, core infrastructure, and patent non-disclosure. First, Japan’s experience on restrictions of rare earths imports and seafood export bans by China, disruptions due to the first China-US trade war, the COVID-19 pandemic, and Chinese dominance in emerging technologies, are all instructive for Japan.

In this context, Japan seeks to secure access to strategic goods and critical materials such as aircraft materials, cloud technologies, fertilizer inputs, industrial tools, LNG, rare‑earth magnets, robotics, and ship equipment. And given the double‑edged nature of economic interdependence, avoid overdependence on certain markets and suppliers.

Second, Japan will closely work with the private sector to develop critical technologies in the maritime sector (e.g., advanced sensing and data analytics, AUVs), space and innovation (automated satellite constellations, hypersonics, miniaturized UAVs), and cross-domain areas (AI security, cosmic ray detection, GPS, next generation batteries).

Third, Japan will safeguard core infrastructure (communications, finance, postal service, transportation, utilities) and screen foreign-made equipment and investments for possible infiltration and industrial espionage. Fourth, Japan will enforce the non-disclosure of patents on dual-use technologies. In relation, industries, technologies and intellectual property will be protected through trade controls under the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act, along with tightened security clearances, consular vetting and cyber security under the Act on the Protection and Utilization of Critical Economic Security Information.

In line with ESPA, Japan will engage in industrial promotion and maintain superiority in computing (advanced semiconductors, quantum technology), clean tech (perovskite solar cells, advanced energy storage, critical minerals), and biotech (antibiotics, synthetic biology platforms). Japan will collaborate with the academe and industry to create an economic intelligence ecosystem by integrating government agencies, think tanks, and the private sector (public-private strategic dialogue). This ecosystem will cultivate economic security experts through research and information sharing, table-top exercises, and supply chain analysis.

Japan will further leverage its network power to strengthen geoeconomic partnerships and global frameworks by coordinating industrial policies with international regimes such as the Australia-UK-US (AUKUS) security partnership, Chip Four (C4), G7, Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Supply Chain Resilience Initiative), and the Global South.

Against this backdrop of a rapidly evolving international economic order, Japan will pursue autonomy in disruptive fields – through competitiveness and cross-border learning – and preserve strategic indispensability by preventing leakages of sensitive technologies (advanced engine and composite materials, multifunctional manufacturing and inspection equipment, optical fibers).

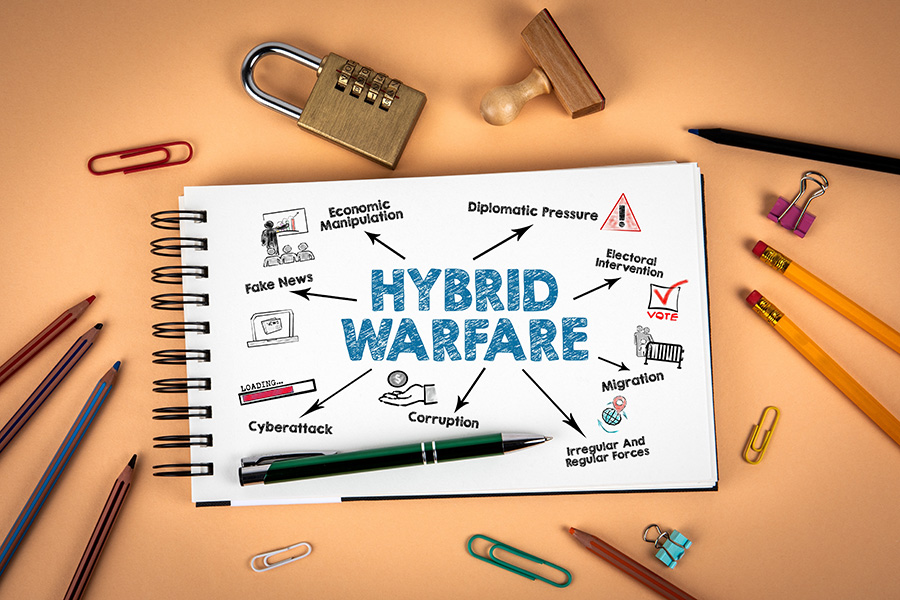

Amid chip wars, civil‑military fusion, decoupling (de‑risking), de‑dollarization, friend‑shoring (reshoring), and submarine‑cable threats driven by competing compliance systems and regulatory regimes, economic security figures more prominently in peacetime. This trend reflects the increasing use of economic statecraft and strategic trade policies — including sanctions and counter‑sanctions, inbound and outbound investment screenings, export controls (Foreign‑Produced Direct Product Rule), investment restrictions (U.S. Entity List, China Unreliable Entity List), and measures to secure the Information and Communications Technology and Services (ICTS) supply chain.

Sources of Economic Insecurity

For Southeast Asian countries like the Philippines, economic security is not entirely new. The 1991 Philippine Foreign Service Act prescribes that economic security – with a focus on economic development — is one of the Three Pillars of Philippine Foreign Policy. There is also the 2015 Philippine Strategic Trade Management Act which regulates the trading and facilitation of “strategic goods” that could proliferate weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). The Foreign Investments Act of 2022 established the Inter-Agency Investment Promotion Committee (IIPCC) to conduct preliminary risk assessments — together with the National Security Council (NSC) — on critical infrastructure investments and periodically review the Foreign Investment Negative List (FINL). And the Amended Public Service Act of 2023 introduced a national security review mechanism for foreign investments in strategic industries such as airports, shipping industry and telecommunications.

In addition, in the National Security Policy (2023-2028) of the Marcos Jr. Administration, the “national security interest” talks of “economic strength and solidarity” and the “national security agenda” highlights “economic, infrastructure, and financial security”, “energy security,” “transportation and port security.” Given their vital roles in mobility and trade, the NSP flags the potential foreign control of critical and strategic infrastructure, indicating the necessity to review foreign investments in cyber infrastructure, telecommunications, and transportation sectors, while also recognizing the imperative to diversify food supply sources.

For Global South countries, there is a broader view of economic security as they are positioned at the lower level in the “national hierarchy of needs.” For example, the Philippine Development Plan (2023-2028) speaks of economic insecurities arising from poverty, social security, health security, food security, job security, environmental security, and energy security (third most expensive in Asia). This is especially true for Global South countries that do not have perceived hostile actors or have different threat perceptions, economic security equates to opportunity maximization through economic cooperation. This then drives them to align with whoever can offer them economic incentives and support their internal balancing agenda.

In this sense, Japan’s economic diplomacy, along with its public diplomacy efforts, has been very successful, consistently serving as the Philippines’ top official development assistance (ODA) source for quality infrastructure. Since 2022, the Philippines has also been the largest recipient in Southeast Asia of Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) assistance which include grants, technical cooperation, finance and investment cooperation and ODA loans, significantly helping address human security issues. Japan has even expanded its infrastructure diplomacy in the Philippines to the trilateral level by jointly pursuing the Luzon Economic Corridor with the US. In fact, Japan has similarly addressed the infrastructure requirements of other ASEAN countries through efforts like the JAPAN-ASEAN Connectivity Initiative, which is not surprising why Japan ranks as the most trusted dialogue partner of ASEAN.

From Economic Cooperation to Economic Security Convergence

It is high time for the Philippines to embed economic security into the consciousness of its policy community. Even though the Philippines’ level of economic securitization may differ from Japan’s due to the lack of advanced or emerging technologies, there is a shared objective to secure strategic industries and critical infrastructure, as well as to diversify trade, investment and development partners.

Economic resilience and critical minerals have already figured in the Japan-Philippines-US trilateral discussion. The Philippines has also signed an MOU with South Korea on critical minerals, aligning with global efforts on green energy transition and positions the Philippines in the renewable energy value chain. Notably, the Philippines is in the top seven in the export and supply of nickel, gold, copper, chromite and cobalt.

Under the Chips and Science Act’s International Technology, Security and Innovation Fund, the US designated the Philippines as a partner country to shore up the Philippine semiconductor industry and make it conducive for US investors by funding the training of 128,000 semiconductor engineers and technicians by 2028. Japan could follow through and enable the Philippines to move into the upstream segment of the semiconductor industry. Neighboring countries such as Malaysia have unveiled plans to become a regional tech leader by 2030, Singapore aims to establish itself as a powerhouse in AI, semiconductors and biotech, and Vietnam seeks to become a hub for high-tech investment and innovation.

It is equally important to note that hedging against economic risks and market power dominance should be country-agnostic given the precedence of pandemics, recent calls for a world minus America, and the experiences of both Japan and the Philippines with transactionalism and unilateralism.

In light of mounting economic nationalism and growing risks of economic warfare, the Philippines could have specialized economic security units within the DFA and DTI, and strengthen partnership with the Private Sector Advisory Council (PSAC) to improve inter-ministerial and public-private sector coordination on economic security. The Management Association of the Philippines (MAP) has already urged the creation of an “economic security council.”

Apart from an FTA strategy, the Philippines needs a supply chain strategy and do its homework of adopting a competitiveness strategy which will really ease ways of doing business and accelerate extensive infrastructure upgrades; otherwise, international roadshows to attract investments will be mere lip service.

Lastly, the Philippines should ensure the maintenance of “ASEAN Centrality” by supporting deeper regional integration and external diversification, as a weak ASEAN from within would be vulnerable to market access denial and policy pressures from major powers.

Aaron Jed Rabena

Aaron Jed Rabena is Assistant Professor at the Asian Center in the University of the Philippines and former Visiting Research Scholar at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies