This essay discusses how disasters such as COVID-19 were used as a mechanism to enhance exploitation of Indonesian workers, and how union leaders and labor activists reflected on Indonesia’s labor movement in response to that phenomenon.

The Law Against the People

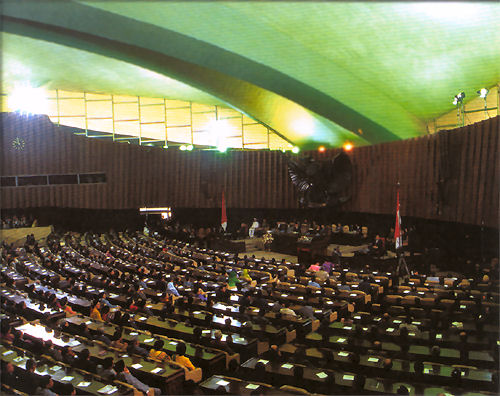

As I write this essay in late March 2025, for days, the streets of many cities in Indonesia have been filled with demonstrators, consisting of students, workers, and the general public, who demand the repeal of the Indonesian Military (TNI) Law, passed by the House of Representatives on March 20, 2025. The new law, a revision to the previous law, is deemed problematic because it contradicts civilian supremacy, with several especially questionable articles that “could blur the lines between civilian and military authority,” reminiscent of, and possibly bringing back, the authoritarian New Order period (Paat & Rivana, 2025; Saputra, 2025; Tempo, 2025). The law’s revision process was also rushed, providing “little opportunity for public involvement or meaningful participation” (Saputra, 2025). Critics have mentioned that such a lack of transparency is a “frequent issue” in the House deliberation and drafting of bills (Tempo, 2025).

Indeed, this should remind us of the “Omnibus Law on Job Creation” (Undang-Undang Cipta Kerja), passed by the House on October 5, 2020, in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, despite widespread rejection by the public. This also led to nationwide protests demanding the repeal of the law (Prasetyo, 2020; Lane, 2020). Prior to its passing, civilian organizations suggested that the deliberation on the bill should be halted, “in the framework of respecting, protecting and upholding human rights for all Indonesian people,” but the process continued under “a cloak of secrecy” (Panimbang, 2020).

The Omnibus Law only benefits capital and its cronies. It amends about 79 existing laws that cover areas such as labor laws, mining regulations, and environmental protections. It aims to attract foreign investments using the same old mechanisms such as labor exploitation and land expropriation. The language used is “job creation”—but of course, the more important question is, “what kinds of jobs?”—although what is being sold is the wellbeing of Indonesian people, and workers in particular, as well as the environment.

In terms of labor issues alone, instead of “creating jobs,” the law increases labor flexibilization and threatens job security. It also leads to the privatization of public goods and services; the attack on various labor rights, including benefits such as sick leave and retirement; the elimination of some important criteria that affect minimum wages (such as inflation), and other aspects (see Panimbang, 2020; Izzati, 2020; Prasetyo, 2020). Not surprisingly, the World Bank has “strongly defended” the law, while the Indonesian Employers’ Association and the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry have also shown their support (Lane, 2020). Global and local capital would profit from the transition to the kinds of jobs (think vulnerable jobs with lower wages, no benefits, and little security) that make enhanced exploitation possible—this can take shape in any mechanism and its supporting policies that in effect reduce workers’ wages and/or force workers to increase their production output.

When I went to Indonesia in mid-2024, I interviewed manufacturing workers, union leaders/organizers, as well as labor activists/researchers in Jakarta and several cities in Banten and West Java.[1] The interviews were part of my research project regarding how workers, among other actors, in countries like Indonesia are affected by, and respond to, “crises” that are triggered by phenomena like the COVID-19 pandemic. But a significant part of the interviews became a conversation about strategies for Indonesia’s labor movement as a part of the Global South. Many of my participants were either directly or indirectly involved in the protests rejecting the Omnibus Law. The union leaders I talked to belong to some of the unions that initiated GEBRAK (Workers with the People Movement), an alliance of several confederations and federations of unions that work together with student, women, environmental, and civil society organizations. GEBRAK was active in mobilizing masses during the Omnibus Law protests, although this was not their first involvement in such mass protests. Lane (2020, p. 3) sees their strategy as building a “broad multi-sector popular movement.” But before we discuss this further, let us go through some of the experiences of Indonesian workers in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Exploiting the Pandemic

It is well-known by now that the COVID-19 pandemic brought devastating disruptions to the highly complex configurations of global commodity chains (see Foster & Suwandi, 2020).[2] A report by J.P. Morgan (2022) describes the supply chain crisis as further exacerbated by the Russia-Ukraine conflict, with ongoing bottleneck effects continuing to occur in several sectors, from metals and mining to chemical supply.

However, things are not always clear when it comes to how such crises affect workers at the point of production: what is the relationship between these seemingly omnipresent disruptions triggered by the pandemic and the Indonesian workers who make shoes, assemble electronics, and produce other commodities for multinational corporations? Unfortunately, the answer may remain vague. In highly complex global commodity chains with the goal of enhancing capital accumulation in this imperialist world economy (Smith, 2016; Suwandi, 2019), phenomena such as the pandemic or the Russia-Ukraine conflict—regardless of their real, possible impact—may as well be another justification for enhancing exploitation.

My participants observed strong patterns across factories: the pandemic, and sometimes, the Russia-Ukraine conflict, became a reason for various exploitative practices. To begin, many workers experienced layoffs (PHK/Pemutusan Hubungan Kerja). The main reason? The factory they worked for, as a supplier for a multinational headquartered in the Global North, had a significant decrease in purchase orders from their client (the multinational). “The pandemic” was often cited as a reason (and to a lesser degree, the “Ukraine war”), implying that multinational clients were having financial problems due to impacted sales, so that they were decreasing orders. But this was difficult to verify, since information regarding client’s orders was often confidential.[3] Sometimes factory management cited disruptions caused by the pandemic as a reason for layoffs, saying that their clients’ products failed to enter the European market, or that materials shipped from other countries got held at port.

And perhaps most importantly, it is worth noting that in many factories, there was a pattern of “relocation,” often after layoffs. The factory owner would either relocate the factory, or build another factory, in another province where minimum wages were much lower than in the current province. Usually, the new factory was built in Central Java, such as in Grobogan. This alone makes the “decreased orders” reason given by management questionable. If it was not about factory relocation, another common phenomenon was replacing the laid-off workers with contract workers (BHL/Buruh Harian Lepas) who were without job security. In some factories, the common trend was to hire “interns” (buruh magang) who were usually fresh high school graduates. The switch to these kinds of precarious work is in line with the Omnibus Law that encourages the flexibilization of the labor market and makes it more difficult to provide job security to workers.[4]

In conclusion, exploitation is enhanced both through lowering wages (through the flexibilization of labor, such as through hiring lower-wage workers in another province or in the form of contract workers) and through increasing productivity. Who benefits from all this? And among those beneficiaries, who gains the most profit (hint: who captures the most value in global value chains)? You can probably answer these questions. This is what critics of the Omnibus Law have pointed out—as a union leader said in his interview with me, the Law is nothing but a “red carpet” for foreign investors.

Reflections on Indonesia’s Labor Movement

How did workers respond to these exploitative practices? Workers whom I interviewed were all unionized. So, they did not just respond, they fought back the best they could through their unions, on the factory level, such as through negotiations with management. Some of these experiences are matters for another discussion. What I want to highlight here is a wider issue regarding how union leaders/organizers and labor activists/researchers see the above phenomena and relate it to their own reflections on Indonesia’s labor movement. In general, my participants agreed that (1) phenomena such as various crises triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic were used as a justification to enhance exploitative practices of workers by both capital and the state, and (2) long-term strategies are needed to build a stronger labor movement.

Although there are some disagreements, most union leaders/organizers (some of them were also factory workers at the time of their interviews) and labor activists/researchers agreed that there needs to be a wider movement than just a narrowly perceived movement of the industrial working class led by trade unions. There are several factors highlighted by different participants. Differences aside, I summarize them here. First, we need an inclusive labor movement that can reach a wider segment of civil society, especially its progressive and radical elements, including the peasantry and feminist organizations. This is how we build a stronger movement, and it is a needed strategy to face state oppression, such as that in the form of the Omnibus Law. GEBRAK was a meaningful achievement, and strategies are needed to keep building up such alliances, especially ones that are not only centralized in big cities. Labor unions themselves must be able to reach out to various segments of workers and know the characteristics and demographic of their workers well so they can adjust and update their strategies.[5]

Second, we also need to think about how to conceptualize better, concrete demands—perhaps formulate our own strong, alternative policies—so we can go beyond being in the “defensive” position (i.e., fighting back against oppressive regulations) every single time.[6] Still, for some union leaders/organizers, what remains important is to build a strong basis for a general strike through continuous consciousness building at the point of production. Therefore, when workers need to shut production down, the “strike structure” is already there.

Third, political-economic, grassroots education for workers that aims to build class-consciousness is crucial. Some participants strongly emphasized that these informal classes or discussion groups should be able to accommodate all workers, especially those who are often excluded from union activities, like mothers who experience the second-shift phenomenon. Fourth, some labor activists also suggest that unions need to think about strategies in revitalizing their function as the basis for social movements. Partly due to the continuous effort by the state to weaken unions (even post-Suharto’s New Order), unions have been somewhat forced to switch their role as social work agencies. To attract membership, many unions compete to offer the most “service” for their members (from distributing food packages to providing ambulance service). With this framework, it is difficult for unions to continue to be a basis for meaningful social movements. This sentiment was echoed by other activists who thought that labor movements in Indonesia can benefit from further radicalization to the Left and widening their networks so they could mass mobilize.

Concluding Remarks

Echoing my participants’ reflections, more dialogue among workers, labor activists/researchers, and union leaders/organizers would be highly beneficial in determining the directions of the ongoing alliances—and to prevent their weakening when there are no “pressing” issues to respond to, such as regulations to reject—and ways to build their militancy. This dialogue should be held regularly in informal, inclusive grassroots discussions that can reach various groups of workers. There are plenty of aspirations, constructive self-critique, and valuable knowledge—all built from meaningful experiences—that my participants offered. All of them are important actors, either directly or indirectly, in the landscape of Indonesia’s labor movement. The time is ripe for us to realize all these considerations and conceptualizations, to bring light in the face of darkness.

Intan Suwandi

Intan Suwandi is an assistant professor of Sociology at Illinois State University, USA. She is the author of Value Chains: The New Economic Imperialism, published by Monthly Review Press.

Notes –

[1] The union leaders/organizers belong to KSN (Confederation of National Unions), KASBI (Indonesian Trade Union Congress Alliance Confederation), and SGBN (The Center of National Workers Movement), while the labor activists/researchers are those currently or previously affiliated with LIPS (Sedane Labour Resource Centre) and P2RI (The Unity of Indonesian People’s Struggles).

[2] In early 2020, more than 90 percent of 1000 Fortune multinational corporations had suppliers that were affected by the pandemic. By mid-April 2020, more than 80 percent of global manufacturing firms experienced supply shortages (Betti & Hong, 2020; Braw, 2020; DeMartino, 2020).

[3] But when unions asked help from labor organizations to check the performance of the factory’s clients, for example, they found that the multinational’s profit had not suffered, but rather increased. In some cases, the factory itself has had an increase in profit, the union representatives found.

[4] There were many other exploitative practices that were discussed. Some of them are supported by governmental policies; they include the decrease of workers’ working hours and, thus, their wages (“no work, no pay” policy), the cutting of wages up to 25 percent in labor-intensive export-oriented industries, and many others that I cannot discuss here due to the limited space.

[5] Citing some labor activists/researchers in my interviews, a highly structured, hierarchical labor union that prevents its higher-ups having proper, clear communication with the workers at the production sites is no longer useful in today’s era of the flexibilization of labor.

[6] A union leader also mentioned the need for fighting in both arenas: through alliances such as GEBRAK, and through the parliamentary system by participating in the newly formed Partai Buruh (The Labor Party).

Reference –

Betti, F. & Hong, P.K. (2020, February 27). Coronavirus is disrupting global value chains. Here’s how companies can respond. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/02/how-coronavirus-disrupts-global-value-chains

Braw, E. (2020, March 4). Blindsided on the supply side. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/03/04/blindsided-on-the-supply-side/

DeMartino, B. (2020, April 13). COVID-19: Where is your supply disruption? https://futureofsourcing.com/covid-19-where-is-your-supply-disruption

Foster, J.B. & Suwandi, I. (2020). COVID-19 and catastrophe capitalism. Monthly Review, 72(2), 1-20.

Izzati, F.F. (2020, October 13). Kill the bill, or it will kill us all. Progressive International. https://progressive.international/wire/2020-10-13-kill-the-bill-or-it-will-kill-us-all/en

J.P. Morgan. (2022, May 25). What’s behind the global supply chain crisis? https://www.jpmorgan.com/insights/global-research/supply-chain/global-supply-chain-issues.

Lane, M. (2020, November 9). Protests against the Omnibus Law and the evolution of Indonesia’s social opposition. ISEAS Perspective, 128. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/ISEAS_Perspective_2020_128.pdf

Paat, Y. & Rivana, G. (2025, March 20). DPR urges dialogue as students protest TNI Law. Jakarta Globe. https://jakartaglobe.id/news/dpr-urges-dialogue-as-students-protest-tni-law

Panimbang, F. (2020, October 21). Indonesia’s return to an authoritarian developmental state. IPS Journal. https://www.ips-journal.eu/topics/democracy/indonesias-return-to-an-authoritarian-developmental-state-4734/

Prasetyo, F.A. (2020, October 17). Neoliberal “Omnibus Law” sparks rebellion in Indonesia. rs21. https://revsoc21.uk/2020/10/17/neoliberal-power-grab-sparks-rebellion-in-indonesia/

Saputra, E.Y. (2025, March 27). Civil society to file judicial review of TNI Law over flawed process, power grab. Tempo. https://en.tempo.co/read/1991283/civil-society-to-file-judicial-review-of-tni-law-over-flawed-process-power-grab

Smith, J. (2016). Imperialism in the twenty-first century. Monthly Review Press.

Suwandi, I. (2019). Value chains: The new economic imperialism. Monthly Review Press.

Tempo. (2025, March 28). Law experts explain why house rushed to pass TNI Law despite public outcry. https://en.tempo.co/amp/1991668/law-experts-explain-why-house-rushed-to-pass-tni-law-despite-public-outcry