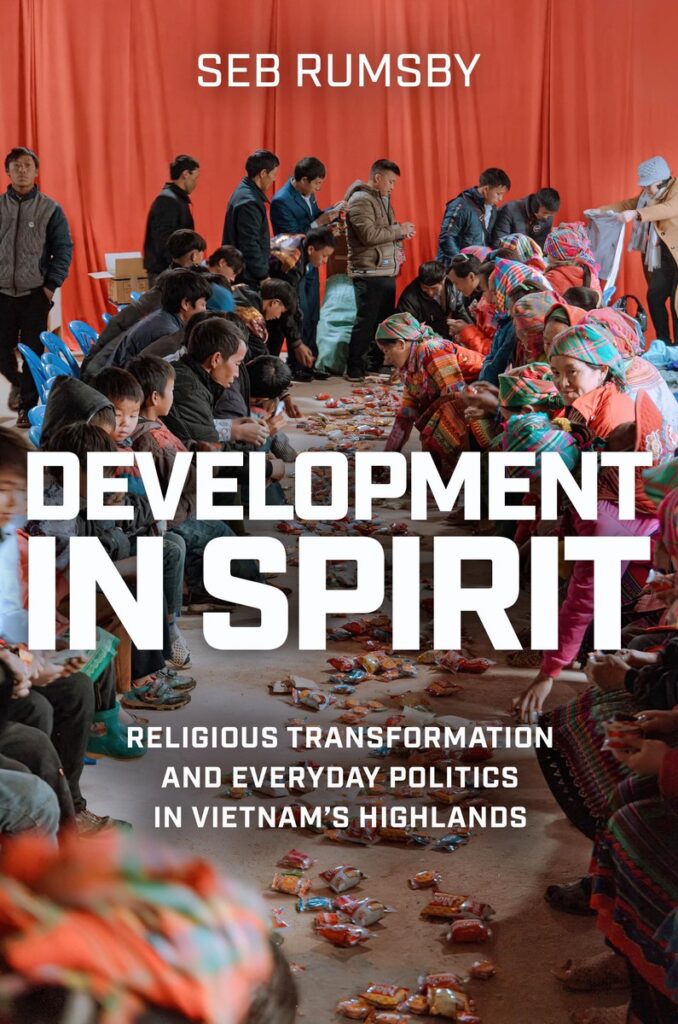

Title: Development in Spirit. Religious Transformation and Everyday Politics in Vietnam’s Highlands

Author: Seb Rumsby

Publisher: Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2023

In recent decades, Vietnam’s integration into the global economy has coincided with a nationwide resurgence of religious devotion. Once criticized (and persecuted) as vestiges of feudal oppression and backward mindsets, religious beliefs and practices have resurfaced as vibrant sources of empowerment and meaning-making. Across various parts of the world, including Vietnam, the dynamic relationship between religion and economic processes has sparked the emergence of ‘prosperity religions’ (e.g. Jackson 2022), ‘occult economies’ (Comaroff and Comaroff 2018), and ‘new religious movements’ (e.g. Chung Van Hoang 2018). Additionally, it has led to a rise of conversions to transnational faiths such as Christianity, indicating that religion offers numerous ways to address the unsettling effects of capitalist market expansion and neoliberal governmentality.

Development in Spirit is a compelling study that explores the economically empowering effects of Christian conversion among ethnic Hmong communities in Vietnam’s northern highlands. Based on long-term, multi-sited research carried out in different Hmong villages, the book skillfully combines vivid ethnographic insights with critical multidisciplinary perspectives to provide a nuanced analysis of Protestant Christianity as an alternative route to development for ethnic minorities in contemporary market socialist Vietnam. In five thoroughly researched and tightly argued chapters, Rumsby convincingly shows that his research participants are “not passive victims or subjects but tactically and selectively engage with powerful state, market, and transnational religious influences” (167). Their primary motivation for doing so is to vươn lên, that is, to ‘move up’ economically and improve their standards of living.

Following the introduction, Chapter 1 delves into the historical and political background of Hmong-state relations in Vietnam. This chapter proves especially useful for readers unfamiliar with the region and with Hmong history, providing essential insights into the wider context of this study. The Hmong, traditionally dispersed across the border regions of China, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand, have become emblematic of James Scott’s (2009) depiction of remote hill communities resisting state influence in the ‘Zomia’ upland areas of mainland Southeast Asia. Over recent years, the Vietnamese government has implemented a host of development programs that have progressively brought the Hmong, along with other ethnic minorities, under closer scrutiny of the state’s gaze. The remarkable success of Protestant conversion among the Hmong reflects historical parallels and has long been viewed by the state as a potential challenge to its authority and to national unity.

Chapter 2 details the broader political-economic transformations unfolding in Vietnam’s highlands and their influence on Hmong livelihood strategies. It introduces three ideal-typical Hmong communities in which different pathways of successful development prevail. In the first, villagers (30% Christians) selectively engage with modernity by agentively pursuing a diversified livelihood strategy that complements traditional rice cultivation with work in tourism and hired labor. Villagers in the second community (0% Christians) have embraced state-led development by relying on poverty reduction support and securing posts in the local government. In the third village, people (75% Christians) enthusiastically engage in church-led communal development activities and have chosen a path of “experimentation, innovation, and risk taking” (79). Each of these examples contradicts the prevailing prejudices held by the Kinh ethnic majority against the Hmong, labeling them as “backward”, “stubborn”, and “uncivilized”.

Chapter 3 turns to the rise of new Christian pastors and church leaders as “everyday elites” (81) and explores their role as development brokers in their communities. Three extended case studies offer insights into the various strategies by which Hmong Christian leaders leverage their external networks, expertise and spiritual authority to influence local political economies and mobilize development from below. Their overall success attests to the creative political and economic agency of local Hmong elites, even if their actions occasionally clash with state agendas and create uneven outcomes within the community.

Chapter 4 examines in further depth how neoliberalism has impacted on the everyday lives of both Christian and non-Christian Hmong. Drawing on Foucault’s concepts of governmentality and ‘technologies of the self’, Rumsby investigates the intersection between the state’s developmentalist discourse, its vision of civility, and Christian (Protestant) ideals of progress. This convergence has imbued Hmong communities with a strong ‘will to improve’. Consequently, both state-led development initiatives and religious conversions play integral roles in fostering the formation of new economic subjectivities among the Hmong. On the negative side, however, these subjectivities also provide a breeding ground for socio-economic inequalities and intolerance toward more ‘traditionally’ oriented members of the community.

In Chapter 5, Rumsby scrutinizes the gendered nature of conversion and the role of women in Hmong religious transformation. While women frequently become the first in the family to convert to Christianity, this doesn’t inherently signify resistance to the patriarchal norms governing Hmong society. Instead, argues Rumsby, Christian conversion can be seen as a form of “patriarchal bargaining” (136) initiated by women to alter their husbands’ undesirable behaviors, such as excessive drinking and violence against their wives, while also improving the overall status of women within the family.

The book concludes with a final chapter that succinctly summarizes its main contributions. Overall, Rumsby’s thorough analysis makes a groundbreaking contribution to the study of grassroots development in the context of Christian conversion in Vietnam’s northern highlands. While readers with a primary interest in religious movements may wish for some more detail in this particular area, Development in Spirit deserves particular praise for effectively portraying the complexity and diversity of Hmong economic life in present-day Vietnam. Furthermore, it highlights the value of ethnographic research for understanding the way “development” is perceived and dealt with at the grassroots level. This book will appeal to students, researchers, policy-makers, and practitioners from various disciplines, including development studies, economics, social anthropology, religious studies, and Asian studies.

Reviewed by Kirsten W. Endres

Kirsten W. Endres is Head of Research Group at the Department “Anthropology of Economic Experimentation”, Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle/Saale, Germany.

References

Chung Van Hoang. 2017. New Religions and State’s Response to Religious Diversification in Contemporary Vietnam. Tensions from the Reinvention of the Sacred. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Comaroff, Jean, and John L. Comaroff. 2018. “Occult Economies, Revisited.” In Magical Capitalism, eds. Brian Moeran and Timothy de Waal Malefyt, pp. 289-320. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jackson, Peter A. 2022. Capitalism Magic Thailand. Modernity with Enchantment. Singapore: ISEAS.

Scott, James C. 2009. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.