Development issues in border areas between two countries are often highly complex. From a microeconomic perspective, this complexity is reflected in the production and consumption decisions of cross-border residents, influenced by historical, political, and social factors from both sides. If these factors were entirely different or completely identical, the challenges for empirical studies would be minimal. However, in most cases, some factors are shared while others differ—and the degree of these differences varies. Furthermore, these factors interact with one another, often in a cause-and-effect relationship. This intricate complexity highlights the importance of using contextual evidence in empirical research focusing on border areas.

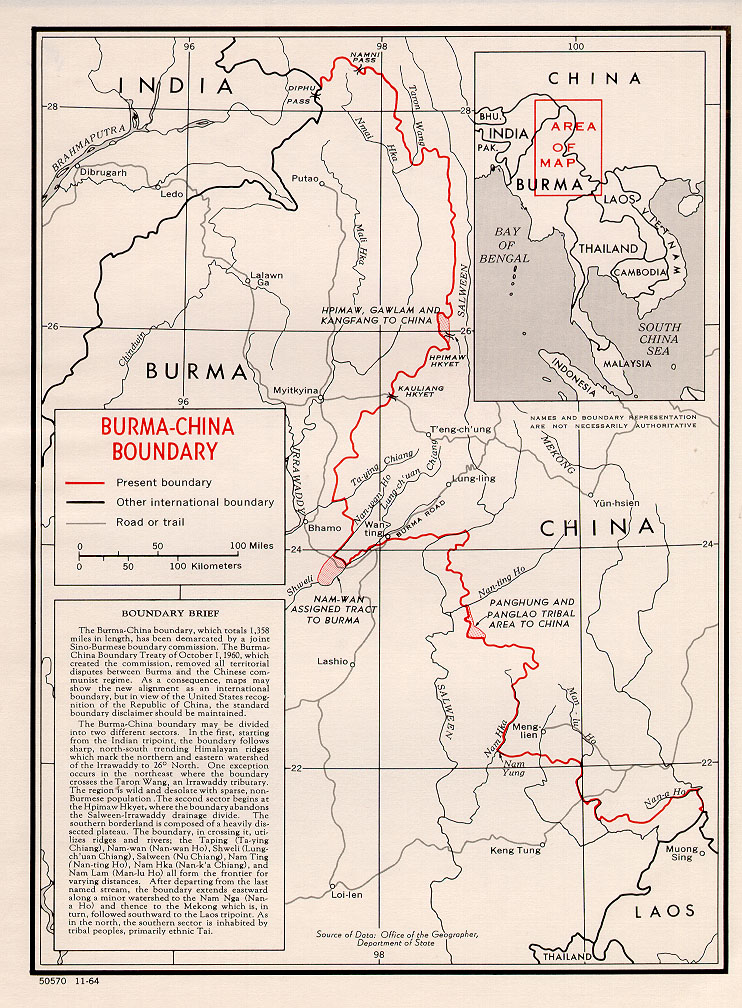

Over the past 12 years, I have conducted extensive investigations across villages along the Myanmar-Yunnan (China) border (see Figure 1). My research draws on village- and household-level data from these sampled villages, as well as individual-level data from cross-border residents. In this article, I use the case of Kokang, Myanmar, to illustrate how contextual evidence explains development challenges in this border region.

Until the 1990s, Kokang, situated along the Myanmar-China border, was part of the “Golden Triangle” and depended on opium cultivation for nearly a century. Locals grew poppy in the mountains to produce opium. However, the opium market was primarily on the China side of the border. While opium fetched high prices in the final market, the prices paid to local farmers were quite low, leaving most of them struggling to survive.

With the global rise of anti-drug movements in the late 1980s, including in China, Kokang’s opium production faced significant international pressure. Most regions had to comply with China’s anti-drug campaign by officially banning poppy production. However, this campaign also pushed rural households—who had long relied on opium production—into extreme poverty. These farmers, already struggling to make ends meet, suddenly lost their primary source of income. Without international aid and located in areas controlled by ethnic armed groups beyond the reach of central government finances, these regions had no choice but to depend on their own resources.

In the search for alternatives to opium production, two main options emerged: sugarcane contract farming in collaboration with Chinese sugar companies and the gambling industry. The demand for both industries primarily comes from the other side of the border in China. The development of these alternatives is also influenced by the economic and institutional differences between the two regions. Are these alternatives effective? What impact do they have on local households? Have income levels and welfare improved? To answer these questions, we need to model utility maximization, a strength of microeconomics. Specifically, it is essential to provide evidence of the profitability of these alternative crops or industries and evaluate the welfare status of former opium farmers before and after the transition.

Regarding sugarcane cultivation, which has become the primary alternative crop (see Figure 2), my hypothesis is that it has increased household income and welfare levels. However, my research indicates that in 2013, after the anti-opium campaign, the average annual income from sugarcane contract farming was approximately $2,300, while the income from opium in 1998 ranged from $700 to $1,400. Considering inflation—I calculated that the cumulative inflation rate from the 1990s to the 2010s was around 185%—the economic benefits of sugarcane compared to opium did not increase significantly. Moreover, the high labor intensity of sugarcane farming, along with the potential health risks associated with pesticide overuse, indicates that welfare levels may have actually declined rather than improved.

It is also important to note that sugarcane and poppy are cultivated under completely different geographical conditions—sugarcane typically thrives on low-altitude land, while opium is grown in mountainous areas (see Figure 3). As a result, highland opium farmers, who relied solely on poppy for their income, faced significant challenges when attempting to transition to sugarcane cultivation. The differences in terrain made it difficult for them to adopt sugarcane as an alternative crop. Many of these farmers struggled to adapt their farming practices and techniques to meet the requirements of sugarcane cultivation, leading to uncertain economic outcomes and potentially exacerbating their existing challenges.

In the meantime, the government decided to transform Kokang into “the next Macau” by opening 14 casinos, creating around 10,000 jobs. These job opportunities primarily targeted unmarried young women, most of whom worked as casino dealers (see Figure 4). My hypothesis is that these women, coming from poor households and previously seen as financial burdens, suddenly became the main breadwinners inside a household. However, regressions reveal an intriguing trend: girls from poorer households tend to send home less remittance. Instead, a substantial portion of their earnings is spent on personal consumption—such as new clothes, smartphones, and entertainment.

This personal consumption is largely directed toward dating and socializing. The contextual evidence shows that these activities are viewed as investments in the future—specifically, the pursuit of finding a Chinese boyfriend to marry and move to China. If they successfully secure a Chinese husband, they can avoid returning home for arranged marriages and escape their economic struggles. This desire is particularly strong among the daughters of poorer households, as they are reluctant to marry into local families with similar economic statuses. Moreover, their parents, unable to afford a decent dowry, tacitly approve of their daughters’ “unfilial” behavior—choosing not to send money home and instead spending it on personal enjoyment. For these parents, the investment in marriage represents a trade-off in terms of remittances. This choice does not maximize overall household utility: once the daughters decide to invest in marriage, their contributions to family income decrease, further limiting the poverty alleviation effects of casino employment for former opium farming households.

In both of these studies, the role of contextual evidence is to enrich the details of household utility maximization models and eventually to support or challenge hypotheses. In the first case, the agricultural alternative necessitates a careful distinction between pre-ban opium farmers and sugarcane contract farmers, a distinction that can be challenging to clarify during the hypothesis formulation stages. In the second case, the contextual evidence regarding the casino alternative focuses on understanding the motivations behind income flows—seemingly irrational personal expenditures—which actually connect back to marriage customs and reverse selection in matchmaking and dowry norms.

Ultimately, the role of contextual evidence is to add details to possible causal inferences. It is essential to emphasize that formulating hypotheses based on economic theory is fundamental. In other words, we should never “find a problem to fit the answer” or “find an answer to fit the problem” when conducting empirical research.

YALEI ZHAI

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University

zhai@cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp

References –

Zhai, Y and F. Koichi (2016)Opium Eradication and Rural Socio-Economic Transformations in Kokang, Myanmar:·With Special Focus on the Impact of Sugarcane Contract Farming by a Chinese Company (in Japanese) . Ajia Keizai, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 2-33.

Zhai, Y and H, Kono. (2021) The Poor Receive Less: Remittance Behavior of Female Migrants in Myanmar, Journal of International Development 33(5) pp.910 – 926