What does it mean when your own country does not care about you? Among others, this question swirls in my mind when I recall the places that we visited during the 47th Southeast Asia Seminar.

Roaming the vicinity of the new Kawthoolei Karen Baptist Bible School and College 1 just across the stream from the Mae La “temporary shelter area,” 2 I was intrigued by the rustic cadence of the place. En route to the school, one is greeted by a sprawling organic vegetable garden. A larger, equally thriving plot of homegrown plants occupies the space behind the school. In one of the school halls, children spiritedly rehearsed a song with their teacher; in an open kitchen, men and women prepared food for a wedding the following day; carefree teenagers played soccer in the nearby dirt field. It was almost a scene-by-scene mimicry of simple village life in my home country, the Philippines—and a far cry from the crushing poverty many Filipinos endure every day in some of the world’s densest slums.

This is not to say that people living in and around the Mae La “temporary shelter area” have it so much better than my poorest countrymen. To downplay the plight of the former is an impossible task: Forcibly displaced or voluntarily migrating from their ancestral homelands, many of these people are still compelled to live in a state of liminality as “politically unqualified beings” without adequate juridical protections from the Thai government (cf. Tangseefa, 2007, 2016). What struck me as remarkable, however, was that even as many of them are considered “aberrants to the Thai nation-state” (Tangseefa, 2007, p. 248), they have the kind of physical space and community life beyond the reach of many poor Filipinos. Even more surprising was the sophisticated social support system of border communities such as this (see Tangseefa, 2007 for an introductory overview of how this system came to be in this “temporary shelter area”). Beyond the “temporary shelter area,” nowhere was that system more evident during the seminar than in the health services catering to the needs of the forcibly displaced, voluntary migrants, or other marginalized people along the Thai-Myanmar border region: the clinics of the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit, including its impressive tuberculosis clinic; the famed Mae Tao Clinic co-founded and led by Dr. Cynthia Maung; the Migrant Fund insurance system; even a dedicated help desk at the Mae Sot General Hospital (see Tangseefa et al., 2019; Tschirhart et al., 2021).

In contrast, for many poor Filipinos—people inscribed within the law as full citizens of a country and supposedly endowed with all the rights and privileges that citizenship entails (see Tangseefa, 2007)—indignity has become a way of life. While such an “undignified life” may perhaps be unexceptional relative to other Global South settings (where life can be worse), it is nonetheless so pronounced, so loudly enmeshed within the fabric of Philippine urban society, that to ignore it is virtually impossible. At the Philippine General Hospital 3 where I trained as a medical student, for example, it is an ordinary sight to see the poorest of the poor line up by the hundreds in the wee hours of pre-dawn just so they can be seen by a physician. Meanwhile, across the country, the majority of people are only one catastrophic health event away from poverty; when such an event does occur, dignity is quickly done away with as people literally beg for help from government officials and agencies (Lasco et al., 2022).

Critically, whereas forcibly displaced people and voluntary migrants living in and around the “temporary shelter area” of Mae La have been made “perceptible” 4 through the particular health system available to them, in the Philippines, there appears to be a long, troubling history of refusing care to citizens in most need of it—to render imperceptible the particular objects of the status quo’s disdain. As it happens, these are also the very citizens in most need of caretaking, if not nurturing), who simultaneously lack and require access to basic resources more than others.

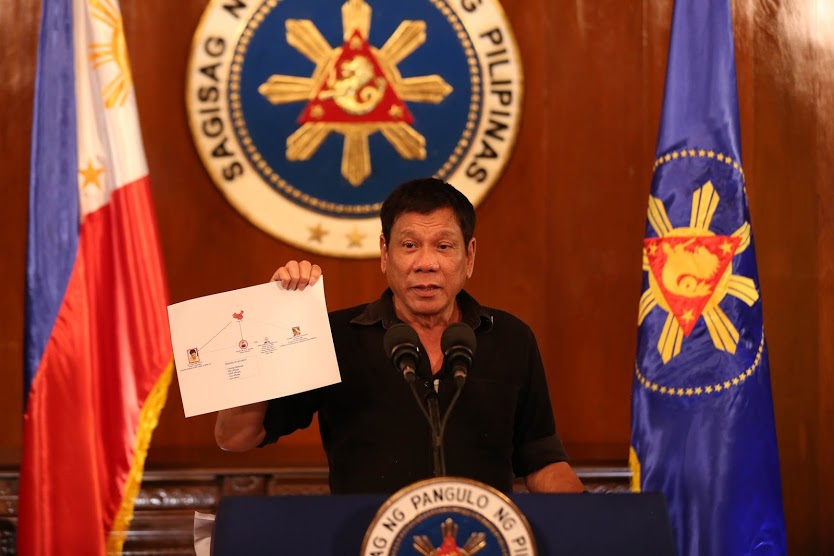

In recent memory, nothing exemplifies this form of selective disdain more clearly than the Philippine state’s treatment of people who use drugs in the country. Across six intense years, the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte launched a deadly, anti-drug campaign that became its banner policy. Ostensibly a crusade against illicit drug use, its conduct quickly exposed it for what it truly was: a “war on drugs” that claimed tens of thousands of lives (Ratcliffe, 2020) and described by experts and human rights organizations as a “genocide” (Simangan, 2018) and a “war on the poor” (Brolagda et al., 2021). As a drugs researcher, I have encountered stories of fractured families, orphaned children and widowed wives, ordinary people witnessing in plain sight the murders of their loved ones or suddenly finding themselves caught amidst a flurry of bullets in their own communities. Targeted by the state, poor people who use or are accused of using drugs have been driven further from the resources and services they need, further entrenching them in a cycle of marginality (Arquiza-Legarde, 2023; see also Yu et al., 2023).

One would think the blood-drenched campaign would have attracted more opposition, but statistics show that in his final year as president, Duterte—and implicitly, his policies—remained wildly popular (Bacelonia, 2022). Scholarly and popular analyses seeking to explain Duterte’s allure have run aplenty: The Japanese social scientist Wataru Kusaka (2020), for instance, has incisively demonstrated the emerging moral subjectivities surrounding support for the drug war, while the Filipino anthropologist Michael Tan (2021) has historicized the villainization of people who use drugs to account for present-day views toward them. Such intellectual investigations notwithstanding, during the six years of Duterte’s reign, much of the country allowed the drug war to go on.

Even more demonstrative of the institutionalized culture of hate—and the consequences that await those who dare to genuinely care—is the plight of the indigenous peoples of Mindanao in the Philippine South. Popularly collectivized under the term “Lumad,” these peoples have endured decades of relentless, state-sponsored violence, frequent accused of being or harboring communist rebels and targeted through extrajudicial killings and other forms of (often fatal) harassment. Alongside this history of violence is, unsurprisingly, the fact that their ancestral lands are some of the most resource-rich in the country—and therefore fertile targets for the hegemonic, neoliberal machine for whom “development,” whatever this word means, must prevail at all costs (Alamon, 2017; Dressler & Smith, 2022; Espiritu, 2022). And at the very core of all this: again, marginalized people, in this case living in remote communities with some of the poorest access to health services in the country.

It should go without saying that there are still those who have resisted the Philippine state’s machinations, working tirelessly to ensure that care continues to reach ordinary citizens. Organizations and collectives like StreetLawPH, IDUCare, and RESBAK, for instance, were some of the most active alliances opposing Duterte’s drug war. But resistance—operating hand in hand with “care” and exercised either vocally or quietly—also has its consequences.

The case of Dr. Natividad “Naty” Castro, a community doctor who has devoted much of her career to serving impoverished communities (including the Lumads) in Mindanao, comes to mind. In 2022, Dr. Castro was arbitrarily arrested by members of the police force and armed forces. She was accused of being a member of the New People’s Army (the armed wing of the country’s Communist Party) and of being involved in the “kidnapping and serious illegal detention” of a member of the Citizen Armed Force Geographical Unit, the Armed Forces’ auxiliary branch known to operate militia-style among communities (Gomez & Gallardo, 2022). Tellingly, the trumped-up cases brought against Dr. Castro were dismissed in court—but not after she had been detained for over a month (Rita, 2022).

What is most striking about Dr. Castro’s ordeal is how unremarkable it was: It is the same fate endured by countless activists, organizers, union leaders, and environmental defenders every year in the country, many times resulting in their deaths (see Dressler, 2021; Lorenzana, 2021). Apparently, when you care about the oppressed and marginalized to the point that you are perceived to be fighting (against) the status quo, you become an enemy in the eyes of the state. Even doctors striving to improve the health outcomes of the most left-behind communities are not exempt from this view.

[Statement of the UP CSSC and UP CS FSTC on baseless designation of Dr. Naty]MAKING MEDICAL SCIENCE SERVE THE PEOPLE IS NOT TERRORISM!

Last Jan 30, Dr. Natividad Castro was baselessly designated as a terrorist by the ATC for “violating” several provisions of the ATA of 2020. pic.twitter.com/Xu3Z2o6yMI

— UP Diliman College of Science Student Council (@upcssc) February 1, 2023

Quite revealing of the way the entire infrastructure of political authority in the Philippines operates, in 2023, Dr. Castro was designated a ‘terrorist’ by the fledgling Anti-Terrorism Council (Rita, 2023). The Council itself was born through the Anti-Terror Law (Republic Act No. 11479, 2020), widely regarded as yet another repressive piece of legislation and assault on basic freedoms (Gavilan, 2021), whose railroaded passage by the Duterte government during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic was a clarion disclosure of state priorities at a time of exacerbated precarity. Notably, even the country’s highest court struck down certain provisions of the Law (e.g., criminalizing dissent) as unconstitutional (Buan, 2021).

A separate, far earlier instance involving health workers further demonstrates the state’s predilection to villainize genuine care and make enemies of those who dare to act against it. In mid-2020, after the initial, strictest lockdowns had been lifted and the country was engulfed by its first, massive surge of Covid-19 cases, medical societies and frontliners—normally a conflict-avoidant bunch—collectively voiced their objections to the government’s flailing pandemic response and called for another period of stringent stay-at-home measures; the President, in typical Duterte fashion, responded by daring them to mount a “revolution” (Ranada, 2020). Duterte’s taunt was spoken in jest, of course, but “revolution” also happens to be a loaded word in Philippine society—so strongly linked to the ongoing communist armed movement, its connotations harking back to the political violence of the decades prior to and under the Marcos dictatorship. Revolution is communism is rebellion is resistance is people like Dr Castro.

Where care is villainized, state-inflicted violence flourishes, accessible healthcare is relegated to an afterthought, and catastrophic health expenditure becomes an even more common, life-altering possibility. It no longer matters that those inscribed within the law (see Tangseefa, 2007) as citizens of the country are actually owed such care. To demand change—loudly, boldly, unrelentingly—in the Philippines is to risk being accused of rebellion or terrorism by the state, which is ever intent on suppressing dissent yet somehow also undetermined to enact lasting reforms for (the health of) its citizens. It is to risk becoming an enemy of the state.

Reflecting on the Anti-Terror Law and the storied history of counter-insurgency in the Philippines, the novelist Glenn Diaz (2020, para. 8) wrote:

That the (Law) was railroaded at a time of unimaginable suffering for many Filipinos ought not to surprise… Systems can only hold off their contradictions for so long, and the reckoning is always punctual. And as it flails for dear life, its guardians resort to naming sprees: enemies, terrorists (gerilya, insurrectos, remontados, filibusteros, etc etc). Again the missing predicates. Enemies of what? Terrorists to whom?

Vincen Gregory Yu, MD

Ateneo de Manila University, University of Sydney

Banner Image: Manila, Philippines – Homeless Filipino people sleeping at the street. Photo: aldarinho, Shutterstock

Notes:

- What we visited was already the “rebuilt” school, the previous infrastructure having been destroyed by a fire in April 2012 (see Thansrithong & Buadaeng, 2017). ↩

- The quotation marks around “temporary shelter area” are meant to indicate the need to problematize the use of this term, which is—in brief—an assertion of the statist discourse being put forward by the Thai nation-state with regards to forcibly displaced peoples. For a problematization of this usage, see Tangseefa (2007). ↩

- The Philippine General Hospital in the City of Manila is a tertiary public hospital designated as the national government referral center. As such, it receives hundreds of thousands of patients each year from all over the country, especially in and around the catchment area of Greater Manila. ↩

- My use of the words “perceptible” and “imperceptible” in this paragraph borrows directly from Tangseefa (2007). ↩