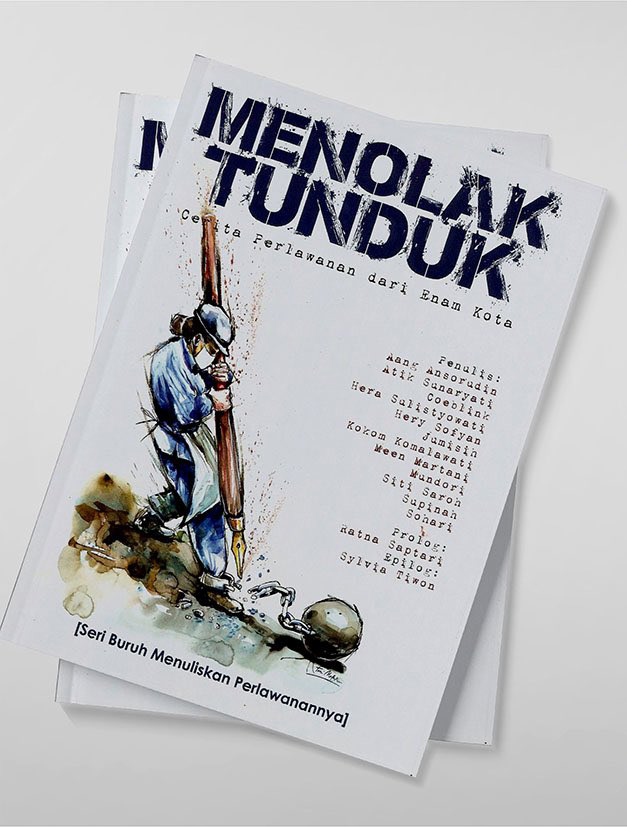

- book 1

Menolak Tunduk: Cerita Perlawanan dari Enam Kota

Authors: Aang Ansorudin, Atik Sunaryati, Coeblink, Hera Sulistyowati, Hery Sofyan, Jumisih, Kokom Komalawati, Meen Martani, Mundori, Siti Saroh, Supinah, Sohari

Editor: Tim LIPS

Publisher: LIPS & Tanah Air Beta, 2016

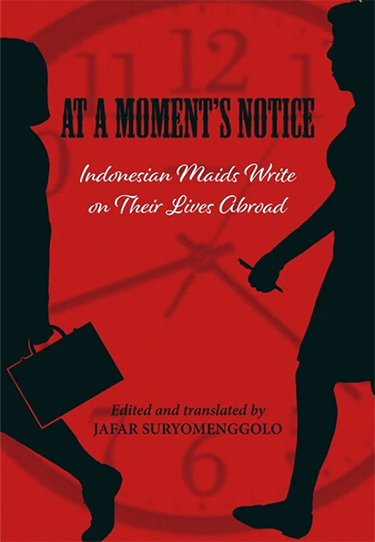

- book 2

At a Moment’s Notice: Indonesian Maids Write on Their Lives Abroad

Editor: Jafar Suryomenggolo

Publisher: NIAS Press, 2019

Indonesia’s Labour Movement and Labour Studies in Indonesia

Indonesia’s labour movement has entered a new phase of independent self-organisation. After 32 years of corporatist control under Suharto’s New Order authoritarianism, workers’ success in movement organising indicates the rise of their political power in shaping state policies. Though still relatively marginal in mainstream politics, the labour movement has successfully become a pivotal element of social forces and movements. The rise of labour studies within Indonesian higher education institutions amidst mainstream social sciences is indicative of this resurging political influence of labour.

However, reference sources of Indonesia’s labour movements in Indonesian are still limited. In this context, two books titled “Menolak Tunduk: Cerita Perlawanan Dari Enam Kota” and “At a Moment’s Notice: Indonesian Maids Write on Their Lives Abroad” offer a new narrative for labour studies in Indonesia. Written directly by workers and activists of Indonesia’s labour movement, these two books present a crucial breakthrough for Indonesian labour studies.

Menolak Tunduk: Cerita Perlawanan dari Enam Kota – Indonesian Labour Movement from a First-Person Perspective

This book, a continuation of a similar book entitled “Buruh Menuliskan Perlawanannya”, presents the life stories of labour movement activists, including women, and their perspectives on the movement and its politics in Indonesia. Contributors of this book are mostly trade union activists and leaders identified as ‘red trade unions’, which are more left-leaning and tend to use progressive-radical approaches when facing employers and states in their struggle such as doing strikes with occupying factories.

Themes concerning working condition under the Labour Market Flexibility (LMF)— a regime of work that breeds and perpetuates precariousness of the working-class—dominate the authors’ writings in this book. Vividly, all stories show workplace vulnerabilities and insecurities experienced by workers under the LMF, manifested in outsourcing and other casual working systems. Moreover, this book’s stories, especially those of women writers, show that the problems they face are not only confined to their conventional workplace, a factory, but also another hidden and often unacknowledged workplace: home.

This book also offers a detailed trajectory of the workers’ lives, from their original social milieu until they became workers and labour activists. Through these writers’ writings, we can find that migration from villages to cities, limited access to education, and family’s economic difficulties, crossing with each other and sending workers to their present place. In this case, it corroborates the semi-proletarianisation process in urban areas, mainly caused by land grabbing or gentrification.

Furthermore, through this book, we can understand the complexity of the Indonesian labour movement. The book provides stories on how they organise themselves, how they educate manufacturing workers about workers’ right, and how they resist companies or state policies affecting the working class. The authors wrote the transformation of the workers’ class consciousness through activism in sufficient detail in this 426-page book.

The book also provides stories that would open the mind of anyone who wants to understand the labour movement and its resistance against capitalist exploitation. The authors of this book, for instance, tell in great detail their experience in organising strikes, including its challenges and achievement. The issue of workers’ education within the union also receives significant attention to these stories.

Most importantly, this book presents a class analysis deriving directly from the workers’ viewpoint. The workers’ stories show the long-standing adage that the workers’ interests and the bosses, the capitalists, conflict with each other. Other than strikes, class antagonisms between the two classes are also displayed, for instance, in stories about union-busting: how companies prohibit union officials from organising activities. Issues regarding women’s reproductive rights at work, such as neglected maternity and maternity leave rights, are also a significant concern for many authors in the book and shows another face of class antagonism.

At a Moment’s Notice – Migrant Workers’ Struggle amidst the “Crisis of Care”

In contrast to “Menolak Tunduk”, a book entitled “At a Moment’s Notice: Indonesian Maids Write on Their Lives Abroad” which is a collection of fictional stories written by Indonesian migrant workers, offers a different narrative. To illustrate, in the first part, the eight short stories, the authors illustrate the relationship between migrant workers, who work as domestic workers, and employers who employ them, as a complicated relationship since they do the care work.

A crucial aspect left unmentioned in the book is that worker-employer working relationships lie in the crisis of care. According to Fraser (2017), the crisis of care is a contradiction of social reproduction, such as unpaid domestic work, in capitalism. On one side, social reproduction has a crucial role in capitalism. On one side, social reproduction has a crucial role in capitalism. On the other hand, the capitalist orientation for relentless accumulation tends to be unlimited and has made social reproduction’ responsibility externalised to women. Thus, the work burden goes to women, who are seen as responsible for social reproduction roles in society.

In “At a Moment’s Notice”, fiction becomes the medium to convey Indonesian migrant workers’ experience. There are four sections of short stories in this book. First, labour relations between workers and employers; second, migrant workers’ sexuality and sex life; third, the workers’ moonlighting experience, and lastly, their stories after returning to Indonesia. In general, all the stories featured in the book successfully portray the lives of Indonesia’s migrant workers who are working in distant countries.

Although it does not become a significant part of this book, some short stories show class conflict elements. As home become a particular workplace for most migrant workers, their relationship with their employers become more complicated. The short stories display how the labour relations of migrant workers in the employer’s home become blurred. In this case, the migrant workers sometimes also act as a family member of their employers. Thus, the short stories ask us to think about labour-relations within the context of the crisis of care.

In the second part, the problem of violence in marriage and date relationships faced by migrant workers and the problem of reproduction health, including safe abortion, are packaged well through several short stories. The solidarity within the migrant workers, especially when they face hard times, is also highlighted in this part. Moreover, the short stories also highlight their sexuality, a rare topic discussed in Indonesian labour studies. The stories of migrant workers who also moonlight as sex workers are highlighted in this book.

Similarly, this book also illustrates what migrant workers face when returning to Indonesia. Their feeling when they finally become a “free person”, as they identified themselves as a “slave” when working as migrant workers, or their feeling when they finally meet with their loved ones, are told through the short stories. At the same time, these stories also speak a lot about migrant working conditions in foreign countries.

What can be seen from this book is that the migrant workers succeeded in illustrating their working conditions in various parts of the world through fiction stories. These worker-authors successfully use fiction as a means to express their experiences and imagination, both as migrant workers who work far away from home and as women.

Life History: Introduction to the Analysis of Labour Conditions in Indonesia

These two books manage to capture the workers’ conditions and the Indonesian labour movement. The whole story presented by the labour activists in these two books is subjective. However, the point of view of the workers presented in this book is essential. Particularly, when it comes to pedagogical discourse in which the experience comes directly from the subject—in this case, labour movements—is crucial.

Thus, these two books are essential life-history works for labour studies in Indonesia. As one of the pivotal research methods, life history can highlight people’s everyday experiences shaped by their political economy condition. Therefore, it is also essential to employ this method in labour studies and other studies, such as urban studies or agrarian studies.

The many women labour activists who wrote in the first book and all-female migrant workers who wrote the whole story in the second book also showed a more feminist gesture of the post-New Order labour movement. Moreover, these two books also explain workers’ migration journey: the first from villages to cities/urban areas, and the latter from villages to foreign countries.

Although these books have succeeded in building readers’ sympathy in the labour movement, readers need to read other books to understand the context of labour politics shown in the two books. It is because these two books are similar to the results of fieldwork. It then requires an analytical framework to read without being trapped in the “commodification of misery stories” told by the workers in these two books.

However, not all Indonesian workers’ stories are covered in these books. Therefore, it is critical for other workers, for instance, gig economy workers—including freelancers, to write their own story and tell their life and experiences through their perspectives.

Fathimah Fildzah Izzati

Researcher at the Centre for Political Studies, Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI)