My academic career is marked by a prolonged focus on Japanese diplomacy and Asian politics. Currently, my research concentrates on Japan’s role in the health and social welfare of refugees and minorities. The consequences of the ongoing political instability in Myanmar have been severe, leading to a humanitarian crisis of staggering proportions. By the end of 2023, over 2.6 million individuals across the nation were displaced. Living in makeshift settlements, they face harsh conditions and lack access to essential resources like safe drinking water and adequate shelter (OCHA, 2024). Many of these forcibly displaced people, while commonly referred to as “refugees” in a broad sense, reside in what the Thai state designates as “temporary shelter areas” along the Thai border. This terminology reflects Thailand’s non-signatory status to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, leading to the official classification of those fleeing from Burma/Myanmar as “people fleeing fighting.” Despite the absence of the term “refugee camp” in the official Thai lexicon, various stakeholders have used this phrase widely along this border region (Tangseefa, 2007, 2016).

Similarly, significant numbers have sought refuge in camps near the Bangladesh border, underscoring the regional impact of the crisis (OCHA, 2023). Japan is providing humanitarian assistance to these refugees. Given the ongoing civil war in Myanmar and the refugee situation in Thailand and Bangladesh, it is necessary to verify whether Japan’s humanitarian assistance has been successful. Furthermore, in Myanmar, ships provided by Japanese ODA are being diverted to transport soldiers and weapons, and Japan’s Diet is discussing the ramifications of whether some Japanese-funded projects benefit the Myanmar armed forces (Human Rights Watch, 2022).

Amid these important developments and concerns, Japan’s policies toward the region must be adequately studied. Therefore, I not only conduct field research in and around Myanmar, but also empirically trace Japan’s development cooperation and humanitarian assistance amid the ongoing regression of democratization in Myanmar, specifically examining the status of pacifist principles and human rights due diligence.

The 47th Southeast Asia Seminar, “Health, Border, and Marginality: Toward Transdisciplinarity?” offered a rare opportunity to enrich my understanding. The seminar was co-organized by the Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS), Kyoto University, and the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (SMRU) and was held from December 7-14, 2023 in Tak Province, Thailand, which borders Myanmar.

The Power of Collaborative Learning to Address Inter-Connected Challenges

The seminar focused on the complexities of border regions affected by protracted armed conflicts, disease, and socio-economic challenges. In learning about and discussing these complexities, participants explored two main issues: the appropriate research engagement for such spaces and the role of transdisciplinarity as a research approach. Transdisciplinarity is a collaborative endeavor to address societal challenges and bridge the gap between academia and civil society. As such, the seminar consisted of a series of lectures and exposure trips across the districts of Mae Ramat, Mae Sot, Phop Phra, and Tha Song Yang. This created opportunity for deep engagement on several inter-connected issues not only in an academic sense, but also offered a chance to learn directly from various stakeholders. The seminar covered key topics such as problem-solving, knowledge co-production, ethical dilemmas, and the role of donor communities. It also aimed to challenge traditional academic norms and create space for marginalized voices. While the Thai-Myanmar border was used as a case study, the seminar also acknowledged that similar challenges exist in numerous countries with protracted armed conflicts.

From the outset, the informal orientation and welcoming dinner set a tone of collaboration, signaling the depth of discussions to come. This initial gathering was more than a mere meet-and-greet; it laid a foundation for future partnerships. Following this, the insights shared by Francois Nosten and Fumiharu Mieno, among others, were clarion calls to understand the nuanced challenges of malaria control and healthcare delivery in areas marred by political instability. Visiting residences and communities on the outskirts of the Mae La “temporary shelter area” was a poignant reminder of the real-life implications of our scholarly discussions, grounding our theoretical debates in the stark realities faced by marginalized communities.

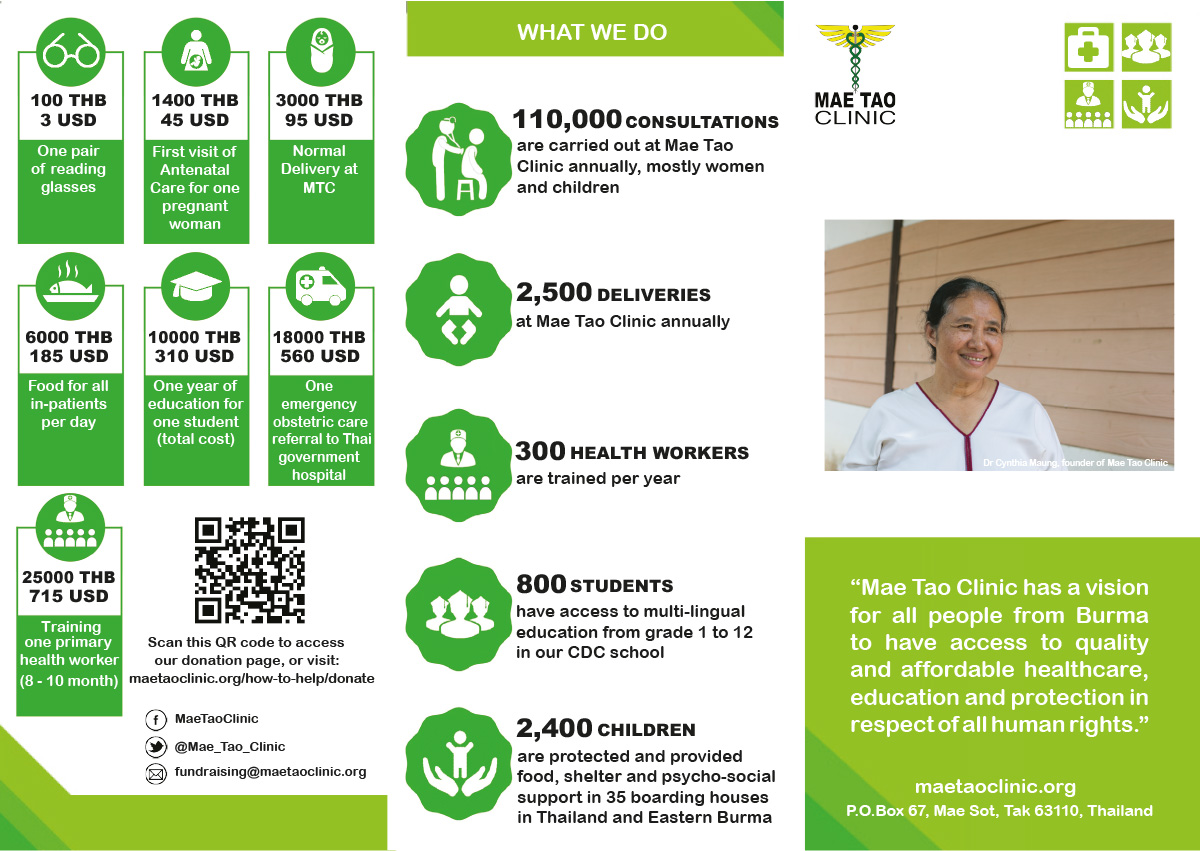

Each session, whether an in-depth analysis of the political crisis in Myanmar, a focus on Muslim communities, or a presentation by the Karen Refugee Committee, offered a unique lens through which to view the multifaceted challenges of marginality. Interactions with community leaders and members provided a human face to the issues we often discuss in abstract terms. These included visits to Mae Tao Clinic and Thoo Mweh Khee Migrant Learning Center, which demonstrated the resilience and resourcefulness of communities in adversity. Dr. Cynthia Maung’s lecture and the following discussions underscored the human aspects of health and marginality, offering lessons in empathy and effective action.

The seminar reaffirmed my belief in the importance of bridging academic research with on-the-ground realities. The insights gained from the discussions, site visits, and direct interactions with affected communities and healthcare providers have enriched my understanding of the complexities of delivering healthcare in politically unstable and marginalized settings. As I reflect on this seminar, it is also clear that the journey toward understanding and addressing marginality is ongoing. The lessons learned here are not just academic; they are a call to action for scholars, practitioners, and policymakers alike to engage more deeply with the realities of those living on the margins.

Overall, the 47th Southeast Asia Seminar was a profoundly enriching and transformative experience. The discussions and interactions among participants from various fields—anthropology, political science, human rights and humanitarian affairs, Asian studies and refugee studies, medicine and health, global health sociology and social policy, development studies, and sustainability science—were a reminder of the importance of bringing together different perspectives to address complex global challenges. The invaluable opportunity for participants to hear directly from those most affected by the issues at hand not only emphasized the importance of listening to and learning from marginalized communities, but also highlighted the need for policies and practices that are effective, compassionate, and respectful of the dignity of all individuals. The seminar challenged participants to think critically and compassionately about the issues of health, border, and marginality. The experiences and insights gained from this seminar can inform and inspire future research, policy-making, and practice. This will influence the development of more effective and empathetic regional policies and practices, contributing to a more just and equitable world. To pursue this goal, particularly during times of crises, diplomacy plays a pivotal role.

Japan’s Policies amid Post-Coup Crises: A Diplomatic Balancing Act?

In June 2023, the Japanese government approved its first Development Cooperation Charter in eight years. The charter states that Japan will focus on improving food and energy security as well as digital and other infrastructure while addressing poverty eradication and enhancing the quality of aid. This policy move is a significant point of interest in my work, as it underscores Japan’s evolving approach to international development and humanitarian assistance. The new charter is Japan’s response to China’s use of infrastructure development and aid to increase influence over developing countries, often saddling them with debt and strengthening control. The new charter, and the National Security Strategy of December 2022, indicate that development cooperation will be a pillar of Japan’s regional policy going forward. Japan is aiming for a “more effective and strategic” offer-type Official Development Assistance (ODA), bearing in mind the strengthening influence of the Chinese government in developing countries, especially in Southeast Asia. 1

However, the situation in Myanmar presents a stark contrast to these aspirations. The February 2021 coup and its ongoing aftermath challenges the principles and goals outlined in Japan’s new charter, highlighting the complexities of implementing a strategic and values-driven approach to development cooperation in a region where political instability can undermine efforts to promote democracy and human rights. Following the coup, the Japanese government suspended new ODA to Myanmar in pursuit of the restoration of democratic politics and the release of democratic leaders. At the same time, it continued more than 30 conventional projects, with a strong emphasis on special economic zones and infrastructure development, including railways and roads. It has also been providing humanitarian assistance through international organizations (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2023a). The strategic decision to maintain ties with the Myanmar armed forces has been part of a broader effort to counter China’s growing influence in Southeast Asia. This approach reflects the complex geopolitical dynamics in the region, where strategic interests often intersect with profound humanitarian concerns. Additionally, Japan’s significant economic partnership with Myanmar, built through development projects, aid, and established businesses, remains key element to their ongoing relationship.

Addressing the roles of informal and private sector actors, such as the Nippon Foundation and the Japan Myanmar Association, the seminar provided valuable perspective on Japan’s dual diplomacy, in which the role of the private sector is becoming increasingly significant. As Japan navigates its relations with Myanmar, it balances its advocacy for democracy with strategic concerns over China and Russia’s influence. As highlighted in our discussions, this approach illustrates the complex interplay between formal diplomatic channels and informal networks in shaping foreign policy.

Human Security in Japan’s Foreign Policy

We must move beyond a purely state-centric and military view of security to embrace human security. This concept prioritizes the safety and well-being of individuals, encompassing economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community, and political security factors to protect from critical threats to lives, safety, and rights. Japan’s incorporation of human security into its foreign policy primarily focuses on “freedom from want.” This contrasts with Canada’s emphasis on “freedom from fear.” The distinction is not merely academic, but also has profound implications for how nations engage with the world, especially in regions fraught with conflict and instability. Inspired by the rich discussions and insights from the seminar, my study examines Japan’s diplomatic maneuvers in response to Myanmar’s 2021 coup through the lens of human security and its operationalization in Japanese foreign policy (Hattori, 2024).

Drawing upon the seminar’s thematic exploration of human security, I investigate Japan’s strategic use of ODA to both foster development and mitigate conflict causes. This approach underscores a preference for non-military means of ensuring security given the constraints of Japan’s constitutional pacifism. The seminar’s discussions on the complexities of human security provided a critical framework for analyzing Japan’s actions on the international stage, particularly at the United Nations, as well as its regional policies.

The exposure trips, especially those to areas impacted by geopolitical tensions, offered a tangible context to Japan’s challenges and strategies in Myanmar. Observing firsthand the consequences of political instability and the efforts to provide aid, I could better appreciate the delicate balance Japan seeks to maintain. Ministry of Foreign Affairs documents, particularly from the International Cooperation Bureau’s Global Issues Cooperation Division and the First Southeast Asia Division, reveal a cautious but strategic response to the coup. As discussed during the seminar, Japan’s reluctance to impose sanctions can be seen as an attempt to avoid pushing Myanmar closer to China, reflecting broader regional dynamics and Japan’s strategic interests.

Reflecting on the seminar’s insights and integrating them with my research, it becomes evident that Japan’s policy towards Myanmar, particularly in the aftermath of the coup, embodies the challenges of applying human security principles in a world of realpolitik. At the same time, critiques of Japan’s ODA policy, as well as private sector involvement and investments, especially vis-à-vis development projects that potentially benefit the military, underscores the tension between ethical considerations and strategic imperatives.

In conclusion, the seminar has enriched my understanding of the multifaceted nature of considering human security in foreign policy. Japan’s response to the Myanmar coup, characterized by a cautious balancing act between promoting human security and navigating geopolitical realities and economic interests, exemplifies the complexities of modern diplomacy. This reflection, informed by the seminar’s comprehensive exploration of human security through exposure trips and discussions, underscores the need for a nuanced approach to development cooperation that carefully considers the impacts of aid on human rights and democracy.

Ryuji Hattori

Chuo University

Banner: Shan State, Myanmar. Photo Jesse Schoff, Unsplash

Notes:

- Offer-type cooperation is a proactive approach in which Japan collaborates with a target country to craft development proposals (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2023b). ↩