Buddhist activism has been a subject of considerable discussion among academics, policy makers, and practitioners in recent years. 1 Buddhist activists, consist of both the Sangha and laity, have sought to promote social justice, campaign for political reforms, propagate environmentalism, and defend their faith against threats and heterodox teachings. In the Southeast Asian context, Buddhist activism conjures the images of Ghosananda and Thich Nhat Hanh’s peace activism, Sulak Sivaraksa’s political and social activism, and of course, the Saffron Revolution that took place in Burma in 2007. However, such activities are not peculiar to the Buddhist majority states of mainland Southeast Asia. The Buddhist communities in maritime Southeast Asia have also had their fair share of activism.

Mention maritime Southeast Asia and what comes to mind is often the Islamic Malay world that includes present-day Brunei, Indonesia and Malaysia, as well as the Catholic Philippines. Singapore stands out as an anomaly because of its dominant Chinese population (about 75 percent), and less known to many, a majority Buddhist population. According to the Singapore census of population of 2010, 33.3 percent of Singaporeans have affiliated themselves with the Buddhist faith. 2 My recent research has focused on Buddhist activism in post-colonial Singapore. My studies have shown that unlike Buddhist activists in mainland Southeast Asia, Buddhist activists in Singapore are less concerned with political reforms, environmentalism, or world peace. Rather, Singaporean Buddhist activists are involved with defending Buddhism against misrepresentations and “heterodoxy,” and promoting social welfare activities.

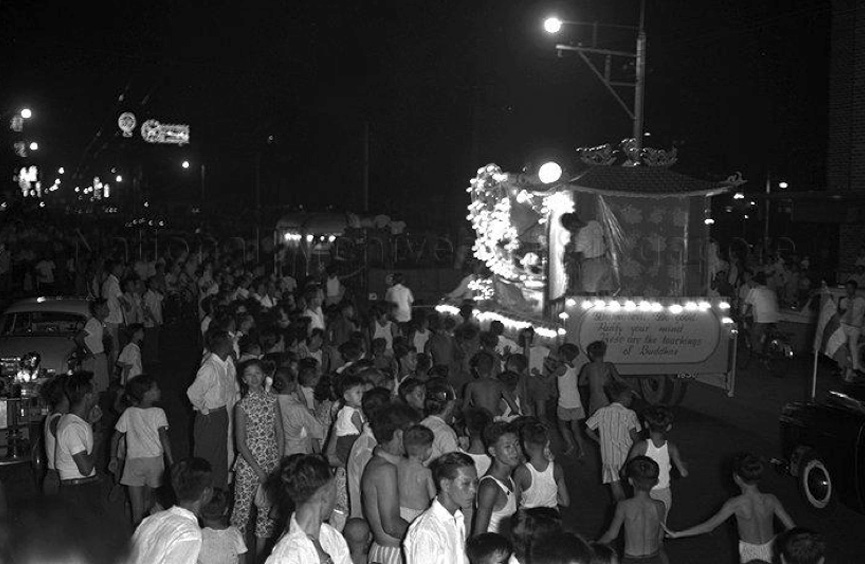

The Singapore Buddhist Federation (SBF, Xinjiapo fojiao zonghui 新加坡佛教總會), a national umbrella institution to represent the Buddhist community, was established in 1949 to serve as a bridge between the British colonial authorities and the various Buddhist organizations in the country. Since the founding, the SBF played a proactive role in promoting the interests of the Buddhist community and played a significant role in lobbying the colonial government for Vesak to be gazetted as a public holiday in 1955. 3 The SBF also lobbied to the colonial government for approval to set up Buddhist cemeteries. In September 1955 and February 1959, respectively, the SBF petitioned the authorities to establish a Buddhist cemetery and to grant permit to construct bridges, drains, roads, a Buddhist shrine, and a dining hall around the vicinity. 4 SBF-led activism in the early years of its establishment was mainly confined to serve the pragmatic and tangible interests of the Buddhist community. Noticeably, the SBF was more interested to persuade the government to assent to their requests rather than to rally Buddhists to defend their faith and correct religious misrepresentations or misguided practices.

Source: National Archives of Singapore

Defending the Dharma

Since the beginning of the 1970s, the SBF, under the leadership of Venerable Hong Choon (Hong Chuan 宏船, 1907-1990), took on a more proactive role in promoting the “defend the Dharma movement” (hufa xingdong 護法行動). The Federation played an important part in lobbying the government to censor foreign films that either contained sacrilegious contents or misrepresented Buddhist teachings. The first SBF-led activism took place in August 1970 to protest against a South Korean film, Dream, which in their words, “insults Buddhism, corrupts morality, and poisons people’s minds.” To protect the “integrity” of the Buddhist community, Hong Choon submitted a petition to the Board of Film Censors to temporarily suspend the screening and to authorize the SBF to review the film. Subsequently, the film was banned in Singapore. 5 Over the next few years, the SBF succeeded in lobbying the Singapore Board of Film Censors to prohibit several other films, including Monks (Chujia ren 出家人), The Four Great Elements are Empty (Sida jiekong 四大皆空), Breasts Revealing Nun (Louru nüni 露乳女尼), The Carnal Prayer Mat (Roupu tuan 肉蒲團), and Moods of Love (Fenghua xueyue 風花雪月). 6

The SBF, however, was not always successful in lobbying the Singapore authorities for the imposition of censorship on films that misrepresented Buddhist teachings. When all else fails, the SBF would launch an education campaign to explain the “misguided” contents in the film. In 1982, SBF received a “tipoff” from the Hong Kong and Malaysia Buddhist associations concerning a martial arts (wuxia 武俠) film, The Shao Lin Temple (Shaolin si 少林寺), starring the young martial artist Jet Li (Li Lianjie 李連杰). SBF was informed that the film distorted the history of Shaolin Monastery and depicted Shaolin monks as violent dog-eaters. First, Hong Choon wrote a letter to Cathy Film Distribution requesting to review the film. However, the film distributor rejected his request. Thereafter, SBF submitted a letter to the Board of Film Censors dated March 8, 1982 requesting to inspect the film. In the letter, Buddhist Federation asserted the need to review The Shao Lin Temple, so as to ensure that the dignity of Buddhism would be preserved and to prevent profit-seeking businessmen from damaging the reputation of Buddhism in their movies. 7 Despite their appeal, the film was eventually allowed to be screened in Singapore. Consequently, the SBF launched an education campaign to educate Buddhists on the history of Shaolin Monastery and the correct practices of Buddhism. 8

As the national representative body of the Buddhist community in Singapore, the SBF played a vital role in defining “orthodox” and “heterodox” Buddhist practices in country. The arrival of new “Buddhist” movements to Singapore became a concern for the Buddhist community. The SBF could not lobby the state to ban religious groups and practices that they deemed to be “unorthodox” as the freedom of religion is guaranteed under the Constitution of Singapore. 9 Therefore, the organization used the defense of the Dharma as a pretext to generate awareness of the heterodox beliefs and practices of these “questionable” groups and warned Buddhists against taking part in their activities. For example, the SBF calls Yiguandao (一貫道), an “evil cult” (xiejiao 邪教) and an “imitation of Buddhism” (jiamao fojiao 假冒佛教), and warns Buddhists against becoming a member of the group. 10 In another instance, the SBF received a petition signed by 73 Buddhist nuns on April 2, 1996 to protest against the “unorthodox” attire of nuns from Jen Chen Buddhism (Rencheng fojiao 人乘佛教). 11 SBF chairman, Venerable Long Gen (隆根, 1921-2011), met with members of the committee, and issued a letter to Jen Chen Buddhism requesting them to abide by the “orthodox” dress code in accordance to the Vinaya and to stop damaging the image of the Sangha. 12 Falun Gong 法輪功, a new religious movement condemned and banned by the People’s Republic of China government in 1999, spread to many other parts of the world. They registered their organization as Falun Buddha Society (Falun foxue hui 法輪佛學會) in Singapore and was permitted to conduct its activities. The SBF published a public statement titled “The name of Buddhism should not be abused” to criticize Falun Gong for misusing the name of the Buddha. They demanded Falun Buddha Society to remove the word “Buddha” from their organization’s name. 13

Social Welfare Activism

Besides playing an active role in rallying Buddhists to defend their faith and correct religious misrepresentations, Buddhist activists are also concerned with social welfare activism. Yen Pei (Yanpei 演培, 1917-1996) was one of the prominent socially engaged monks involved in the dissemination of Buddhist teachings and welfare works. He was a student of the renowned Buddhist reformer Taixu (太虛, 1890-1947) who actively promoted “Human-life Buddhism” (rensheng fojiao 人生佛教) during the Republican period in China. 14 After graduating from Minnan Buddhist Institute (Minnan foxue yuan 閩南佛學院), Yen Pei became a good friend and student of Yinshun (印順, 1906-2005), a renowned Buddhist thinker, best known for his ideas on “Humanistic Buddhism” (renjian fojiao 人間佛教) which had a decisive influence on a future generation of Buddhist monastics. 15

When the Chinese Civil War broke out, Yen Pei and Yinshun left mainland China for Hong Kong in 1949 and then moved to Taiwan in the early 1950s. Eventually, Yen Pei decided to migrate to Singapore in 1963 and became the abbot of Leng Foong Prajna Auditorium (Lingfeng bore jiangtang 靈峰般若講堂). After settling in Singapore, Yen Pei became an active Dharma teacher and promoter of “Humanistic Buddhism.” 16 By the time he stepped down as the abbot of Leng Foong Prajna Auditorium in 1979, he saw the need for Buddhists to be socially engaged and to give back to society. Yen Pei found a new calling to help the poor and needy, and therefore decided to establish the Singapore Buddhist Welfare Services (SBWS, Xinjiapo fojiao fuli xiehui 新加坡佛教福利協會) in 1981.

Yen Pei’s social welfare activities can be categorized into three major areas: elder care and filial responsibility, organ donation and kidney dialysis, and drug prevention and rehabilitation. First, Yen Pei was concerned with the welfare of the poor and elderly. He gave a series of sermons on the Buddhist perspective of elder care and filial responsibility that were subsequently published in the SBWS monthly newsletter Grace Monthly (Cien 慈恩). 17 He highlighted that many needy elderly were living below the “poverty line.” 18 Therefore, Yen Pei played an active role in promoting food distribution and public assistance. The SBWS volunteers conducted regular house visits to call on needy elderly in the neighborhood and bring them food and other daily necessities. 19 Subsequently, he founded the Grace Lodge Home for the Aged (Cien lin 慈恩林) in January 1985 to provide shelter for homeless female elderly, regardless of race or religion. 20

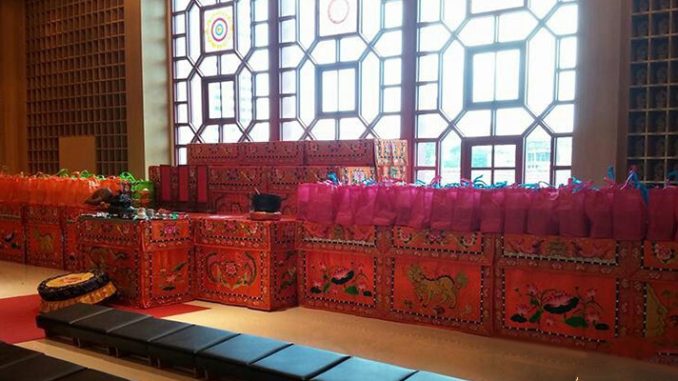

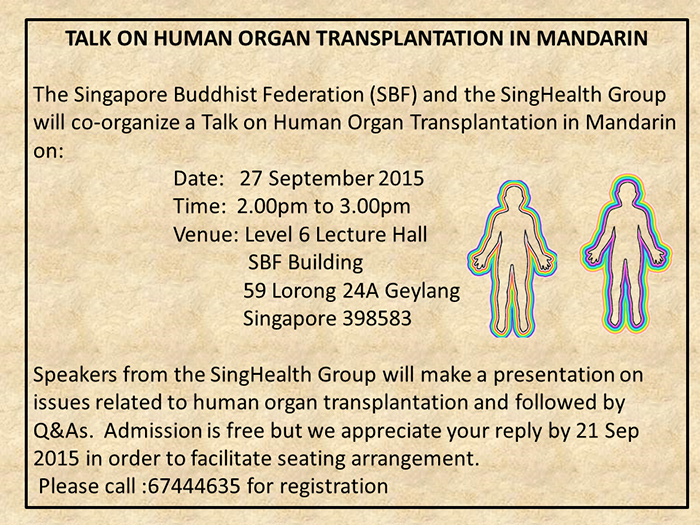

Second, Yen Pei was an active champion of organ donation. He believed that organ donation is in line with the Buddhist teachings of compassion and loving-kindness. Yen Pei promoted the idea that “Buddhism encourages all Buddhists to donate kidney or other useful internal organs to the sick” and “should participate actively in the launching of kidney donation.” 21 To general awareness of the Buddhist community, Yen Pei organized the “Kidney Donation: Buddhist View & Medical View” seminar on September 4, 1983. Subsequently, he founded the Singapore Buddhist Welfare Services-National Kidney Foundation Dialysis Centre in the northeastern part of Singapore. SBWS pledged a long-term commitment to kidney patients and became the first religious organization to contribute an annual S$700,000 operational cost to support a secular dialysis center. 22

Source: Xinlu 心路 (Singapore: Buddhist Cultural Center, 1997), 97.

A third concern for Yen Pei was the problem of drug abuse in Singapore. He emphasized that drug abuse is “harmful to one’s health,” “ruins a person’s future,” and “upsets the peace and prosperity of the society.” He also stressed that the Buddhist precept opposes intoxication. Nevertheless, Yen Pei pointed out that Buddhists should be sympathetic to former drug addicts and help them to overcome their “psychological and material instabilities.” 23 In 1993, he established Green Haven, the first and only Buddhist halfway house in Singapore, to support former drug addicts in their recovery. Green Haven provides 6 to 12 month residential rehabilitation and treatment program for former drug addicts. It assists former drug addicts in seeking both accommodation and employment during the final phase of their rehabilitation program, and help them return to their family and reintegrate into society upon successful completion of their residential rehabilitation and treatment. 24

Conclusion

Unlike Buddhist activism in other parts of Southeast Asia, Buddhist activists in Singapore did not lobby the government for political reforms, protest for social change, or promote environmentalism. Since the strict laws in Singapore prohibit religious and civil society groups from organizing street protests and demonstrations, Buddhist activists were careful not to get on the wrong side of the law and antagonize the state authorities. Instead, they lobbied and petitioned the state agencies to protect their religious interests and often, in their own words, to preserve the dignity and reputation of Buddhism. Yen Pei appeared quite happy to collaborate with the state authorities. He was a pioneer member and Buddhist representative of the Singapore Presidential Council for Religious Harmony and often invited government ministers to officiate the opening ceremonies of his social welfare organizations. Therefore, it was no surprise that Yen Pei’s contributions to social activism was recognized and honored by the Singapore government.Yen Pei received the Public Service Medal (PBM) in 1986 and the Public Service Star (BBM) in 1992 from the Singapore President. Xinlu 心路 (Singapore: Buddhist Cultural Center, 1997), 82-83. 25 A study of Buddhist activism in Singapore offers an interesting insight into state-society relations. Rather than engaging in militant confrontation with the government or risk antagonizing the authorities by organizing public demonstrations, Buddhist activists adopted firm but peaceful measures to achieve their objectives. Thus, it appears that Buddhist activists co-opted the state to do its bidding, rather than vice versa.

Concomitantly, Buddhist activists relied on their knowledge and understanding of the Buddhist teachings to attack “heterodox” groups, as well as to justify their social welfare activism. Yen Pei was quick to use Buddhist ideas of compassion, loving-kindness, and the precept of not taking intoxicants as practical solutions to secular social issues, including elderly care, organ donation and transplant, and drug rehabilitation. The ideas of Humanistic Buddhism that center on putting one’s faith into action for the betterment of humanity were probably an important source of motivation for Yen Pei as well as other socially engaged Buddhists in Singapore. At a spiritual level, proponents of Humanistic Buddhism believe that enlightenment can be achieved in this world, and therefore, strive to build a pure land on earth. One of the ways to construct a this-worldly pure land is to be an active citizen in addressing and contributing to contemporary issues.

Jack Meng-Tat Chia

Cornell University

This paper is based on the authors forthcoming articles, “Defending the Dharma: Buddhist Activism in a Global City-State,” in Singapore: State and Society, 1965-2015, ed. Jason Lim and Terence Lee (London: Routledge, forthcoming 2016) and “Toward a History of Engaged Buddhism in Singapore,” forthcoming 2016.

Issue 19, Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, March 2016

Notes:

- See, for instance, Andrew Higgins, “How Buddhism Became Force for Political Activism,” The Wall Street Journal, November 7, 2007; The Resistance of the Monks: Buddhism and Activism in Burma (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2009); James Brooks Jessup, “The Householder Elite: Buddhist Activism in Shanghai, 1920-1956” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2010); Lodro Rinzler, “Buddhism and Activism: How Would Sid Produce Social Change?” The Huffington Post, January 5, 2011; John K. Nelson, Experimental Buddhism: Innovation and Activism in Contemporary Japan(Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2013); David P. Barash, “Can Buddhists Be Activists?” History News Networks, February 3, 2014. ↩

- he Straits Times, 14 January 2011. According to the Singapore census of population, Buddhism experienced a rapid growth from 27.0% in 1980 to 31.2% in 1990 and 42.5% in 2000. Nevertheless, the number of Singaporeans affiliating themselves with the Buddhist faith dropped from 42.5% in 2000 and 33.3% in 2010. This marks the religion’s first dip in 30 years. ↩

- Y.D. Ong, Buddhism in Singapore: A Short Narrative History (Singapore: Skylark Publications, 2005), 92. ↩

- Shi Nengdu 釋能度, Shi Xiantong 釋賢通, He Xiujuan 何秀娟, and Xu Yuantai 許原泰, ed., Xinjiapo hanchuan fojiao fazhan gaishu 新加坡漢傳佛教發展概述 (Singapore: Buddha of Medicine Welfare Society, 2010), 61. ↩

- Ibid., 125-126. ↩

- Ibid., 126-127. ↩

- “Yanzhong pohuai sengqie xingxiang de Shaolin si 嚴重破壞僧伽形象的「少林寺」,” Nanyang fojiao 155 (1982): 26. ↩

- You Shi 幼獅, “Cong Shaolin si yingpian lianxiang daode 從 「少林寺」影片聯想到的,” Nanyang fojiao 156 (1982): 18. ↩

- Article 15 of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore states: “Every person has the right to profess and practice his religion and to propagate it.” ↩

- “Qianwan moxin xiejiao 千萬莫信邪教,” Nanyang fojiao 115 (1978): 22. ↩

- According to the petition, the signatories claimed that nuns from Jen Chen Buddhism did not follow the appropriate dress code as stated in the Vinaya (monastic rules) but worn skirts, long-sleeved blouse, and headscarf that resembled Catholic nuns. ↩

- “Fandui rencheng fojiao shangai sengfu 反對人乘佛教擅改僧服,” Nanyang fojiao 324 (1996): 4. ↩

- “Xinjiapo fojiao zonghui wengao: Fojiao mingcheng burong lanyong 新加坡佛教總會文告:佛教名稱不容濫用,” Nanyang fojiao 383 (2001): 1 ↩

- For study of Taixu’s reforms, see Don A. Pittman, Toward a Modern Chinese Buddhism: Taixu’s Reforms (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2001). ↩

- Charles Brewer Jones, Buddhism in Taiwan: Religion and the State, 1660-1990 (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1999), chapter 4; Pittman, Modern Chinese Buddhism, 263-270. ↩

- Yen Pei was a prolific scholar and produced a 34-volume collection of his essays under the title Collected Works of Mindful Observation (Diguan quanji 諦觀全集). He also renovated and expanded Leng Foong Prajna Auditorium during his tenure as the abbot. ↩

- See, for instance, Grace Monthly, July 1983; Grace Monthly, May 1984; Grace Monthly, June 1984; Grace Monthly, May 1985; Grace Monthly, December 1985. ↩

- Singapore has never had an official poverty line. See Grace Monthly, April 1985. ↩

- Grace Monthly, April 1985. ↩

- Grace Monthly, March 1986. ↩

- Grace Monthly, August 1983. ↩

- Grace Monthly, December 1991; “SBWS-NKF Dialysis Centre,” http://www.sbws.org.sg/4f_nkf.html (accessed October 1, 2015). ↩

- Grace Monthly, April 1983. ↩

- “Green Haven,” http://www.sbws.org.sg/4l_gh.html (accessed October 1, 2015). ↩

- Yen Pei received the Public Service Medal (PBM) in 1986 and the Public Service Star (BBM) in 1992 from the Singapore President. Xinlu 心路 (Singapore: Buddhist Cultural Center, 1997), 82-83. ↩

Why are monks in Singapore charging such high fees for a wake chant? Prices range from a thousand to a few thousand dollars. When recommend by funeral directors, the price is even higher, another thousand. But recently I attended a wake and the family told me this monk charged only 350 dollars. Why the huge difference in price?