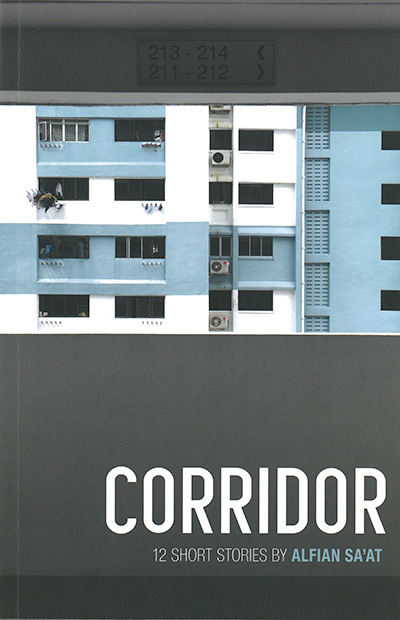

Corridor (12 short stories)

Alfian Sa’at

Singapore: Ethos Books, 2015 (second edition)

“Behind these fantastic stories however, was the faint hope that somehow,

I had found someone who shared something in common with me.” (“Duel” in Corridor 68)

In his collection of short stories, Corridor (first published in 1999), Singaporean writer Alfian Sa’at 1 captures his characters’ hopes and longing for happiness, as well as their internal struggles as they confront their fears, dilemma and prejudices. Many of his main characters find themselves in situations that entrap them as they seek to live their lives as they want to. However, the short stories in this collection are not an attempt at generalizing Singaporean-ness, although just like the quotation from the story “Duel” above, the struggles and hopes of the characters in the stories set in a developed and globalized city-state do become easily relatable to many Singaporeans whose inner desires and personal aspirations may be in tension with society’s expectations and norms, or state policies.

Written in a kind of spontaneity that utilizes the local vernaculars, these stories have with no pretensions about the circumstances the characters find themselves in. Only the characters pretend to be who they are not really in order to be accepted; and this is likely the answer to the narrator’s question – “At that moment I ask myself why the whole world has to pretend” (“Bugis” 128) – as she struggles to confront her own pretensions and the fact that she is no different from Salmah, the Bangladeshis on the train, and the transvestite.

As a post-independence writer, Alfian is not so much concerned with nostagia, or even national identity that is prevalent in postcolonial works, as he is with the disconnect between individual aspirations and state expectations that comes with rapid industrialization and globalization. The stories in this collection, aptly entitled Corridor, deal with the everyday and commonplace. Most of Alfian’s characters are public housing dwellers, as are over 80% of Singapore’s population. 2

These apartments, or ‘HDB flats’ as they are referred to locally, are built by the Housing Development Board (HDB), the national housing authority in Singapore. They have been designed more for their functionality in a kind of pragmatic logic that conceive ‘privacy’ in terms of “state policies, architectural utopianism, and consumer culture” (Chee, 2013, p. 200). Each of these HDB units, i.e., private dwelling spaces, are linked by a corridor, the communal space on each floor, that serves as a boundary between the private and public spaces that residents move into as they go about their daily lives. Ownership of these flats is dependent on one’s conformation to state policies on familial units being heterosexual, and consisting of at least a nuclear family unit such as the ones in “Birthday”, “Corridor” and “Umbrella”.

Extending the imagery of the corridor, Alfian presents these vignettes almost as views through the windows of their lives from outside, i.e., the ‘corridor’, where readers, through the accounts of the voyeuristic first- and third-person narrators, become onlookers. For instance, the first person narrators provide unreliable imaginations of the lives of the other characters at times, like the grandmother in the story “Corridor”, the unnamed man in “Duel”, the unnamed polytechnic student in “Bugis”, or Hafiz in “Umbrella”; they speculate based on their limited knowledge about the other characters they encounter as they peer into their ‘windows’ from the exterior of these characters’ private spaces. At the same time, the characters in the stories are also boxed in or entrapped by societal constraints, just as HDB dwellers are constrained by state policies and social norms.

Alfian’s use of plain, unassuming language that at times foregrounds the local variety of English, or Singlish, serves to provide a voice for these common people whose life stories seldom matter in the larger state narrative of nation-building that privileges meritocracy. Singlish is generally stigmatized by the authority as somewhat uneducated and unintelligible to the international speakers of English, and seen to compromise Singapore’s global competiveness. The use of Singlish with grammatical structures that deviates from standard English and a lexicon that borrows heavily from the local vernaculars in his characterization of the HDB dwellers in his short stories plays up this heartland and cosmopolitan divide significantly.

It is through Singlish that Alfian portrays his main characters as ‘heartlanders’ that are down-to-earth in their local ways as opposed to the the cosmopolitans like Teck How in “Orphans” and Chris in “Umbrella” who are not only educated, but also portrayed to be competitive and more global in outlook. An example of this is when Hafiz, the underachieving narrator in “Umbrella”, with his humble background and predominantly Malay-speaking parents attempt to put on an American accent when speaking to Chris, his Mathematics tutor who is a law undergraduate. Another example is Shirley in “Winners” who is unable to continue the telephone conversation with the staff from East Lion Marketing about a prize that she has supposedly won. She has to trust her husband with the call, only to realize later in the story that the ‘prize’ is simply a timesharing investment marketing ploy, and an empty promise.

What makes Corridor intriguing and yet disconcerting especially to Singaporean readers is its raw honesty in its story-telling that bare the inner struggles of these characters in this increasingly cosmopolitan city-state. Beneath the glitz of the Singapore’s economic prosperity, many of these characters continuously negotiate for any form of recognition in a public space where they merely become numbers and statistics, and where they get conceived as either success stories or underachievers along the lines of socioeconomic status and ethnicity. In that sense, the anthology is an important reading for any Singaporean and those who want to understand its contemporary urban life.

Reviewed by Yurni Said-Sirhan

(National University of Singapore)

Issue 19, Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, March 2016

Work Cited

Chee, Lilian. 2013. “The Public Private Interior: Constructing the Modern Domestic Interior in Singapore’s Public Housing,” In The Handbook of Interior Architecture and Design, edited by Grame Brooker and Lois Weinthal. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 199-212.

Notes:

- As a Malay, Alfian Sa’at does not have a surname. ‘Alfian’ is his given name while ‘Sa’at’ is his father’s name. In this review, I will refer to the writer by his given name, Alfian. ↩

- Housing Development Board (HDB) website: http://www.hdb.gov.sg/cs/infoweb/about-us/our-role/public-housing–a-singapore-icon (accessed 21 January 2016) ↩