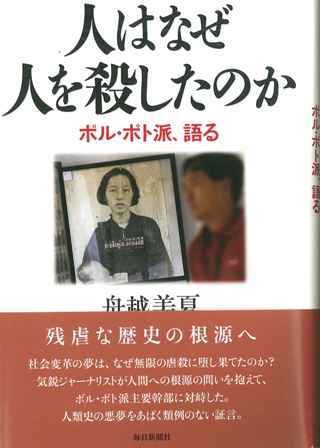

舟越美夏『人はなぜ人を殺したか』毎日新聞社

“Why did People Kill People?” (Hito ha Naze Hito wo Koroshita?)

By Funakoshi Mika.

(2013.Tokyo: Mainichi Shinbunsha)

This book is a record of more than ten years of accumulated interviews with the leaders of Khmer Rouge, Pol Pot’s classmates, the victims of the Khmer Rouge and others by a Kyodo News reporter. The author seeks the answer of the question, “why did people kill people?” through the interviews gathered in this book.

In the introduction, Getting to the root of a cruel history, Funakoshi explains the circumstances of the rise of the Khmer Rouge, the background to the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts, and introduces local staff who were, at that time, employed at Kyodo News. Funakoshi’s father lost his brother during World War II and came to detest what he called the masses. As such, the tragedy that occurred in Cambodia overlapped with her complex feelings about her father. This leads her to want to ask the Khmer Rouge’s leaders the reason for the mass madness that occurred during this period of the killings. Even if she was not able to illicit responses, she wanted to at least see the look on their faces one reason which led her to begin collecting interviews for the book.

The book is divided into eight chapters that each consists of individual interviews. In chapter one, We used our strength justly, Nuon Chea, the Former Khmer Rouge “Number Two,” declares “Our aim was true independence for Cambodia. We were just.” His replies to his responsibility for the deaths of the people was “the purge of enemies and traitors was necessary. There will be no justice if it is not understood that China, Vietnam, and America were going around chasing their own profits at the time” and “even with truth, there is no justice.”

The book is divided into eight chapters that each consists of individual interviews. In chapter one, We used our strength justly, Nuon Chea, the Former Khmer Rouge “Number Two,” declares “Our aim was true independence for Cambodia. We were just.” His replies to his responsibility for the deaths of the people was “the purge of enemies and traitors was necessary. There will be no justice if it is not understood that China, Vietnam, and America were going around chasing their own profits at the time” and “even with truth, there is no justice.”

Chapter two We were ecstatic, focuses on Ieng Sary (Pol Pot’s brother in law, Former Deputy Prime Minister in Charge of Diplomacy) and his reflections on the defeat of Pol Pot’s government. “We became overconfident in our ability to defeat the American army. We began to think that we could do what no one else in the world was able to do.” However, this chapter pulls out his own sense of guilt, as he explains throughout “I never knew what was going on in Cambodia. I was always in foreign countries.”

Chapter 3, An intellectual like me, introduces Khieu Samphan, a Former National Executive Chairman. In interviews with Samphan, the phrase “an Intellectual like me” is repeatedly raised. Yet, when confronted with the question “why was the purge necessary?” he completely hides his real feelings. Samphan states “you cannot understand the situation at that time without understanding the complex history and international politics…I had no authority within the party.” However when pressed by Funakoshi about when the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts was established, his role as a supposed “real intellectual,” and his inability to confess responsibility, Samphan fell silent and shed a tear.

In chapter four, Terrifying condemnation of “counterrevolution,” Suong Sikoeun, a Former Khmer Rouge Regime Senior Foreign Ministry Official, became aware of political activities while studying in Paris and then served under the Khmer Rouge regime as Foreign Ministry News Director. He relates, “I harbored a dream of creating a pure liberated Cambodia, and eliminating all domination of the French government and intervention of Vietnam. I did not face reality.” He also pointed out that one of the failures of Khmer Rouge was the lack of clearly communicate their intentions and policy to the leaderships in the regions.

In chapter five, My beloved Khmer Rouge, Ping Say, a retired teacher, and former classmate of Pol Pot, became devoted to political action while studying in Paris where he dreamt of being able to build a strong country. Upon return home he mixed with the Khmer Rouge and became Pol Pot’s private secretary. He says, “I revered the Khmer Rouge. But, the regime thought more of protecting the state than of protecting the people.” His wife who was also present stated, “The Khmer Rouge sought to protect Cambodia, to teach Cambodians self-sacrifice, patriotism, and independence. I believe that even now.”

In chapter six, Deep-seated ambition, Tep Khunnal, Pol Pot’s Former Secretary, faced the success of the revolution while studying in Paris and returned home to the Khmer Rouge government carrying hope and pride. From 1980 to 1992 he served as the Khmer Rouge Ambassador to the United Nations in New York after which he became Pol Pot’s private secretary. Having studied civil engineering in France, he explains that at that time they didn’t have sufficiently advanced agricultural technology. He pointed out the Khmer Rouge regime’s mistake was putting too much faith in the farmers and the lack of the mutual understanding in the regime.

Chapter seven, Those gentle people introduces an interview with Ly Kimseng, Nuon Chea’s Wife. Kimseng was interviewed after her husband’s arrest and the interview shows how she longs for the old days, “Before the Khmer Rouge era, the Khmer Rouge leaders that visited my house were greeted with a home cooked meal. They were quiet and gentle people.” She insists, “My husband is not the kind of man who would kill someone. His orders were for urban people to adopt the way of thinking of the farmers. ” She relates her loyalty to her husband by clearly stating that “When my husband died, I wanted to die too.”

The final chapter, All people hide brutality leads us to Chan Krisna, a former Kyodo News Phnom Penh Branch Staff, who was born into the upper class in Phnom Penh. His grandfather was the former Prime Minister and his father was a Military Commander under the Lon Nol regime. He carried a deep wound from the murder of his sister and parents during the Khmer Rouge era. However, before the Khmer Rouge regime, his family strongly opposed the left wing. So he knows they also have the brutality. He met Nuon Chea for the first time while accompanying the author. While at first holding on to such hatred (expressed in a desire to stab him to death), he became closer to Nuon Chea then began to take care of Nuon Chea and his wife. He explains his reasons later by stating that “The intent of the Khmer Rouge was not a mistake. I do not want my son’s generation to take over the fight.”

“Is the creation of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts, a search to simplify a complex history, and an attempt to impose all responsibility on a small number of Khmer Rouge’s leaders?”

However, readers should note that these interviews were conducted just before the arrests for the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts. As such, trying to understand the true intentions from those interviewed offers a very limited analysis as they merely form what reads to be a kind of self-defense. The interviews ultimately fail to answer the question posed in the title: “Why did people kill people?” It may reflect her quest to understand the reason behind the killing, but it is indeed not a new question as it is already discussed in a number of other books (see Chandler 1991; Hinton 2004; Short 2005). Therefore, even after reading all their testimonies we are left with the question, what is new here?

On the other hand, there are parts of their testimonies which are convincing. When the Khmer Rouge regime was established, the Vietnam War, the aerial bombings by the American army, and attacks by neighboring countries all bore down upon Cambodia and showed us how at the time, issues in the local region were complexly intertwined. The tragedy in Cambodia occurred during a complex situation that saw no means of escape. So we are left with a question by this book. Is the creation of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts, a search to simplify a complex history, and an attempt to impose all responsibility on a small number of Khmer Rouge’s leaders?

This collection of interviews gives us hope for the future of Cambodia

The core of this book is the central figure of Chan Krisna, the Kyodo News local staff member who lived through the adversity and his testimony. The fact that he became close to Nuon Chea who was one of the perpetrators, is emblematic of the complexity of Cambodian history. As such, even if this book fails to answer its initial question, the reason for this can be partly found in how those who played central roles in Cambodia’s modern history search for ways to overcome deep anger and grief. As such, as a testimony, this collection of interviews gives us hope for the future of Cambodia.

Reviewed by Sato Nao

Research fellow, CSEAS

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 14 (September 2013). Myanmar

References

Chandler, David. 1991. The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution since 1945. New Haven/ London: Yale University Press.

Hinton, Alexander Laban. 2004. Why did they kill? Cambodia in the shadow of genocide. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Short, Philip. 2005. Pol Pot: Anatomy of a Nightmare. New York: Henry Holt Company