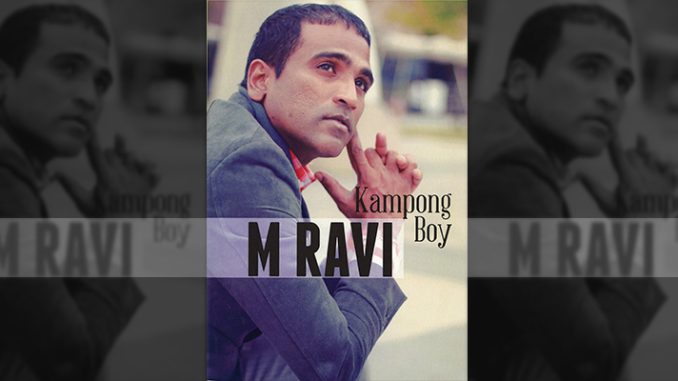

Kampong Boy

Author: M. Ravi

Singapore: Ethos Books, 2013

Southeast Asia has been one of the most fast rising sub-regions in the world since the mid-1960s. Its regional organization, ASEAN, has become a respected driving force behind (East) Asian regionalism, in the meantime it has become a contender to the global preeminence of the West. Significant progress has been made in the advancement of economic and social rights of the region’s peoples since the decolonization process. Yet critique exists both inside and outside the region of the failure to develop stable democratic political systems with strong rule of law and in-built regimes of human rights protection at national and regional levels. In spite of similar trajectories, for many countries, there is high variance among Southeast Asian states’ performance and failure to deliver on both planes – socio-economic rights, on the one hand, and civil-political rights related to the rules and practice of liberal democracy, on another.

Only recently, ASEAN has launched its first regional human rights body – the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR, 23 October 2009) – and agreed upon an ASEAN Declaration of Human Rights (ADHR, 2012), a highly contested document. However, only a handful of states that have genuinely supported this development and have set up National Human Rights Commissions. The overall commitment of ASEAN to international standards of human rights is not only seriously questioned by external observers and civil society in the region but the challenges that the acknowledgement of human rights protection encounters at the national level are very different among its member-states.

Singapore, for instance, ASEAN’s wealthiest state by per capita income, is reluctant to create a National Human Rights Commission. Moreover, Singapore is among the states with the fewest signed international human rights treaties in the region, having ratified only CEDAW, CROC and the anti-genocide convention but with extensive reservations for domestic law. Nevertheless, Singapore stands out as a unique example of a tiny state faring highly, in a comparative sense in Southeast Asia, both in the socio-economic realm and in terms of a functioning system of rule of law. The country is proud of its almost meteoric rise from Third to First World in less than three decades. This has led to profound transformations in the social structure and racial relations of the country, in its cultural, institutional, and political life and, not the least, in the architectonic landscape of the city-state.

Openness towards and embrace of all modern, competitive, cutting-edge global trends have since the 1990s created increased pressure on Singapore’s political elites in their endeavor to sustain, on the one hand, a tough regime of social and political control, on which the economic success story of the country has been built, while, at the same time, to refrain from too much political intervention in the sphere of its judiciary and rule of law systems.

This has most likely opened up a very tiny but hopeful space for human rights activism in the field of law in Singapore that has been sized upon by human rights lawyers such as M Ravi. Using law as a means to induce socio-political change, to advance human rights values, and to defend the rights of concrete people, constitutes a very different kind of socio-political activism than practiced anywhere else in Southeast Asia. Such moves are also taking place in other Southeast Asian countries as well, but the statute and operation of law in Singapore is so much higher and effective than in the rest of the region and comparatively similar to the Western world that may let one hope that, if successful, impacts could run deeper on the legal structure of the Singaporean state and its political system than it could anywhere else in Southeast Asia. And this is the fascinating story that the memoirs of M Ravi tell us.

The book is structured in twenty-nine chapters that narrate the story of his personal growth (chapters one to seventeen) as well as Ravi’s engagement with a few selected human rights cases during his adult professional life as a lawyer (chapter eighteen to twenty-nine). While each chapter can also be read on its own, they follow a linear temporal story-line starting with the broader history of his ancestors, his parents’ arranged marriage and the early childhood spent in the traditional, multiracial Kampong Jalan Kayu (close to Seletar). Kampong’s social life belonged to the early days of Singapore. Chapters one to three thus elaborate on the social relationships in the Kampong and among the community from Tamil Nadu (India), to which his own family belongs. Ravi highlights the patterns of interaction in his broader family and draws portraits of his relatives, such as his aunt, her husband and their daughters, Ravi’s beloved cousins, Maria and Emily.

Chapters four to eight cover the next phase in his life that begins with the exodus of his family from Kampong Jalan Kayu to Ang Mo Kio, one of the newly constructed HDB complexes that also marked a new phase in the social and architectural revamping of the Singaporean city landscape. A large part of the story in these chapters focuses on Ravi’s primary school education at Ang Mo Kio, on the discovery of hobbies – such as debating in Tamil language (and later in English, too) – activity in which he excels and that would accompany him in his adult life. Moreover, his first artistic exposure to South Indian dance (see also chapter twenty-six) as well as spiritual experiences with Hindu and Christian (see also chapters sixteen and seventeen) rituals are key themes of these chapters.

The special relationship with his mother (named Papa) from whom he inherits a passion for cooking Indian cuisine and a broad knowledge of Indian spices, is a highly sensitive but central theme of his biography. Meanwhile, the father figure in his life is reflected upon in stories describing his father’s addiction to alcohol, his verbal and often physically aggressive outbursts towards his fellowmen and most tragically towards his wife, Ravi’s mother. Father’s many transgressions of law led him to jail and constitutes a central theme of this autobiography that stands in strong contrast with Ravi’s future profession as a man of law. At the same time, this life reflection has inspired Ravi’s work as a human rights lawyer, often defending young men who have had a similar background as his own but who were not really given a chance to overcome an unfortunate start in life.

The absence of a morally credible and emotionally stable father brings the family in very difficult situations, in which first of all Papa had had to compensate through hard physical work as a construction worker and a cleaning woman and during the last part of her working life as a helper in a psychiatric hospital. Papa suffered severe bodily and mental strain during her life, which had earned her serious heart and psychiatric illness. It is especially during his law studies in the UK and the beginning of his lawyer career upon his return to Singapore that Ravi becomes heavily involved with Papa’s mental illness. Chapter ten as well as chapters fifteen to seventeen are at length describing his mother health condition and Ravi’s emotional rollercoaster trying to offer her a better life and the medical help she needed. In the last years of her mother’s life, they used to live together in a fancy apartment complex enjoying a warm communion, which nevertheless could not stop the deteriorating mental state of Papa who ended her life. By far, the loving bounds to his mother and the tragic ending of Papa’s life are the deepest and, at the same time, the most devastating dimensions of Ravi’s life and his path to personal and professional adulthood. It is after the death of his mother that he has started taking on sensitive, factually hopeless cases of people convicted to death as well as a series of cases defending fundamental human rights of Singaporean or foreign citizens.

Equally, the relationship with his siblings, especially with the youngest sister also plays an important role in his biography. This is the period of his life, in which he had experienced his first social and intellectual successes, learning a lot about himself and the social world around him. Remarkable especially for a foreign reader are the insights in the social and political history of Singapore that the book succeeds to convey through Ravi’s personal and family history. While Singapore as a social developmental laboratory has provided essential educational opportunities for the Kampong boy moving upwards the social ladder, it has done so within a bound, carefully regulated social space, whose transgression was always coupled to sanctions. This is a lesson that Ravi learns very early in his life, already in the junior college, where he was also for the first time exposed to the limits and perils of opposition politics in Singapore.

Containment of freedom of thought and imagination, narrowness of choice, overregulation and authoritarian attitudes have since then been constant in his life in Singapore as he underwent the compulsory military service, undergraduate university education at the National University of Singapore (chapter nine), his temporary work as a teacher in two Singapore colleges, the second phase of his law education in Singapore allowing him to start a law career in the Lion city as well as during his law career itself (chapters eleven to fourteen). In stark contrast stands the period of his life spent at the University Cardiff in the UK as a law student, where he enjoyed freedom on many levels and an enriching intellectual life but also a tough study schedule due to financial constraints that allowed relatively little free time.

The second part of the book draws on a number of human rights law cases that Ravi has defended in the past two decades. They cover issues such as the compulsory death penalty, the right to freedom of speech, assembly, and religious/cultural expression, the rights of the LGBT community, and the right to by-election. They also uncover the powers to curtail citizens’ political and civil rights inbuilt in the political system of Singapore.

In the death penalty cases, Ravi’s defendants – the Malaysian citizen Vignes Mourti and the Singaporean citizen Shanmugam Murugesu (2003-2005) (chapter eighteen) as well as the Nigerian citizen Iwuchukwu Amara Tochi (2004-2007) (chapter twenty-three) – had all been sentenced to death for the charge of drug trafficking, followed by the rash execution of the sentence. These early cases could not lead to any judiciary successes in terms of altering sentences or, at least, refrain from their carrying out. Nevertheless, the cases brought the issue of the compulsory death penalty to the public attention and triggered some level of social mobilization for either the abolition of capital punishment or at least a judiciary decision stopping its implementation and encouraging a more nuanced use of it. Although the death penalty has not been abolished, a trend towards a more restrained use of it might be expected since in July 2012 the Parliament announced the government’s plans to amend the legal regime of death penalty in Singapore. This slightly amended state could eventually benefit another defendant of Ravi, the Malaysian citizen Yong Vui Kong, who was also sentenced to death in 2010 but whose execution had been on hold (chapter twenty-nine). Singapore has one of the highest execution rates in the world by rapport to its population.

One case regarding the right to free assembly and freedom of expression took place in 2006, when Ravi defended two Singaporean members of Falung Gong in Singapore who protested against the Chinese government’s persecution of the Falung Gong religious movement in China. They were arrested by the Singaporean police and charged for “nuisance”, “displaying insulting writing”, and “harassment” (chapter twenty-four). Although the two protestors were fined and sent to jail for a relatively short period of time, the case was a chance to make important legal claims in favor of the right to assembly of Singaporean citizens. Similarly in 2011, Ravi contested in court the governments’ decision to forbid the use of drums and other noise-producing activities during the yearly Thaipusam festival, a traditional, religious Hindi ritual. Ravi saw this decision as an attempt to curtail the rights of Indian Singaporean community to freely practice its religious and spiritual traditions (chapter twenty-two).

Other cases were politically prominent, involving former and current prime ministers of Singapore who charged opposition leaders (the case of Dr. Chee Soon Juan, leader of the Singapore Democratic Party/SDP and of his sister, Chee Siok Chin vs. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, 2006) of “critical defamation” against the Singaporean government, act understood as a serious threat to the state because it allegedly undermines citizens’ and foreign actors’ trust in the government’s credibility (chapter twenty). Another similar case that occurred in 2010 involved the British journalist Alan Shadrake who was also charged for critical defamation of the Singaporean judiciary system because he published a book critically discussing its shortcomings (chapter twenty-one).

On LGBT rights, the main issue at hand concerns efforts aimed at the abolition of the section 377A of the penal code penalizing homosexual activities, a remainder of the British colonial rule (chapter twenty-five). While the government follows a policy of restrain in the use of this article, such that nobody ought to be arrested or charged based on this legal ground, there is still opposition to giving up the outdated section 377A. In practice, however, people can be still intimidated because in principle the legal context allows prosecution of homosexuality. Ravi and his client who was mistakenly arrested due to the section 377A but whose charge was later altered, successfully attacked the constitutionality of this article in the courts. This has not only boosted the lobby for the removal of this law but it has also encouraged other people to fight in courts for LGTB rights.

In a successful case on the right to by-election, Ravi represented Vellama Marie Muthu in 2011. She filed a petition asking the courts to issue a ruling in favor of her and the other citizens’ right to vote a new parliamentarian to represent their district in order to fill the vacant seat (chapter twenty-seven). In order to avoid open confrontation, the government held elections only a month later.

Kampong Boy is the journey of a freethinker and empathetic spirit who has made the choice to live by his own terms despite external hurdles. Despite the label of bipolarity, Ravi has learnt to see and experience it as an intrinsic feature of his personality that unveils a sharp mind, moral depth, and an intense and empathic approach to choice-making (chapter twenty-eight). By narrating his professional life as a lawyer, the book also illustrates the battle for more and better understanding and protection of human rights in Singapore and reveals the tremendous legal and political limitations that human rights lawyers and activists still encounter in this highly developed country. The book is translated into Indonesian, with a forward by the late Adnan Buyung Nasution, a respected lawyer in the country (published in December 2015). The memoirs by M Ravi are worth reading and an inspiration for all those nurturing justice and normative commitments to meaningful social and political change in the Southeast Asia region.

Reviewed by Maria-Gabriela Manea

Department of Political Science, University of Freiburg