Throughout the 47th Southeast Asia Seminar, participants examined a diverse range of topics from health to border dynamics and marginalization. Amidst the rich discussions, one theme particularly captured my attention: how people residing in borderlands perceive land. While the discourse surrounding refugee issues often emphasizes immediate humanitarian aid and prospective resettlement programs, during the seminar, there was a notable absence of investigations into the enduring bonds that individuals maintain with their lands, even amid the upheaval of economic migration or the search for refuge across borders.

The Significance of Land in a Border Area

One memorable moment during the seminar epitomized this deep connection to land. One hour into an interview, the interviewee asked, “what is your village?” After the research group responded to his question, his face brightened with a smile and his eyes filled with joy as we began to joke with each other and started to build a rapport. The exchange served as a poignant reminder of the enduring significance of one’s birthplace, or ancestral domain, which anchors individuals experiencing migration and displacement. This encounter sparked a series of reflections on the intricate interplay among places of the past (villages), the present (camps and migrant communities), and the future (host countries of resettlement for some refugees 1) in shaping identity and well-being. The native land represents one’s roots and is a cornerstone upon which individuals construct narratives of belonging and connection. Despite decades of physical separation, individuals across generations continue to uphold a deep attachment to their ancestral lands in different ways. The homeland weaves together threads of histories, memories, and identity, eliciting a sense and comfort of home (Tangseefa, 2016).

Despite the profound sense of belonging to a “homeland”, the political, socio-economic, and cultural realities of the refugees along the border add layers of complexity to narratives of land, identity, and belonging. Diverse identities and practices intersect at the liminal spaces of the borderland, giving rise to unique expressions of heritage and belonging. The ways in which different refugee generations navigate their multiple identities—rooted in ancestral lands yet shaped by the realities of displacement and the desire of resettlement for physical and economic security and freedom—offer invaluable insights into the resilience and adaptability of indigenous ethnic groups in the face of adversity. The unique circumstances of the refugees along the Thai-Myanmar border also remind us of the heterogeneity among indigenous ethnic groups worldwide, whose diverse political backgrounds, socio-economic status, and cultural practices shape varied perceptions of reality, strategies of resistance, and identities.

Unpacking the “Land is Life” Narrative

Land and its significance have been at the center of indigenous rights discourse. However, the diverse relationships between indigenous groups and their land remain understudied. To comprehend how the discourse of land developed in the indigenous movement, one must study the interface of indigenous people with colonial power and modernity. Inherited from ancestors and a source of livelihood, land is critical to indigenous society and is to be defended, protected, and nurtured. Cultures and practices are built upon the land through generations, and it is thus more than a physical entity, but also a sacred embodiment of identity, culture, and spirituality. However, indigenous knowledge and cultural practices built upon connections with land and the environment have often been deemed as primitive and backward in Western development discourse.

Western models of development define legitimate forms of knowledge within a discourse characterized by modernization, technological advancement, scientific rationality, and economic growth, extending colonial power by manipulating resources, ideology, and politics (Escobar, 1995; Ferguson, 1994). Throughout colonial history, indigenous people around the world have experienced exploitation of natural resources, invasion of traditional territory, and imposition of colonial ideologies by external forces. Indigenous communities have faced land dispossession, forced relocation, and environmental degradation at the hands of colonizers, governments, and corporations in the name of development and civilization. Large infrastructure and resource extraction projects, such as mega dams and large-scale mining, have resulted in the displacement of indigenous communities in rural areas, generated growing controversies and conflicts (Bebbington, 2007; Escobar, 1995; Ferguson, 1994; Gardner& Lewis, 1996; World Commission on Dams, 2000). The life, heritage, and identity of indigenous peoples have been jeopardized by the loss of ancestral land and sources of livelihood.

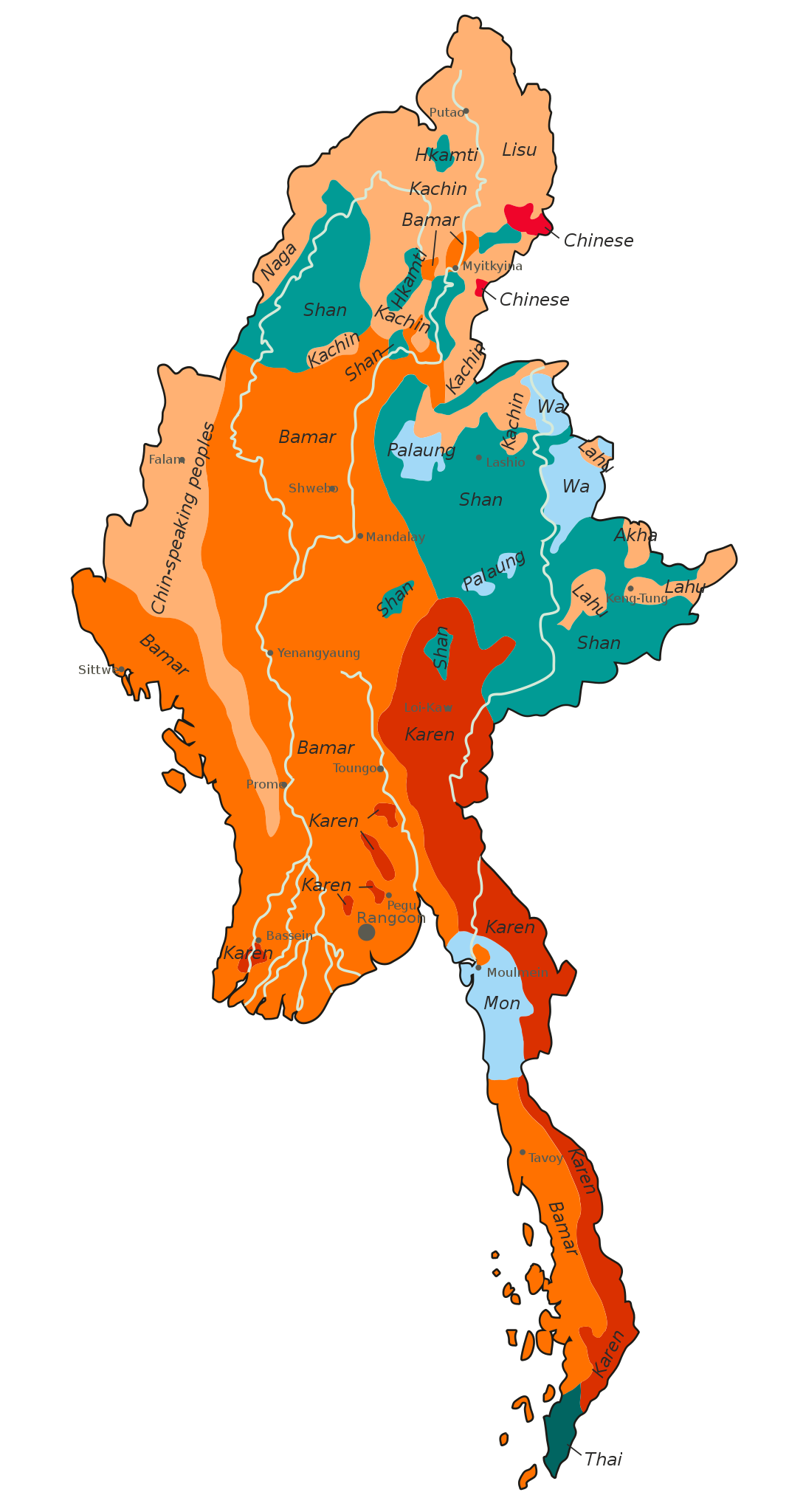

The Hatgyi Dam, a planned hydropower dam on the Salween River in Myanmar’s Karen State. Environmentalists and villagers decry the anticipated ecological and social impacts. Wikipedia

Through critiques of the Western development model, which has caused immense environmental degradation and injustice in the third world countries (Escobar, 1992), there has been a growing recognition of the intrinsic link between indigenous land rights, sustainable development, and environmental conservation since the 1990s. Indigenous knowledge offers invaluable insights into balancing environmental, economic, cultural, and social sustainability for a more holistic approach to managing natural resources. Numerous studies have highlighted the significance of indigenous traditional knowledge and practices to crafting a more sustainable model of natural resource utilization and management (Acabado & Kuan, 2021; Berkes, 1999; Nazarea, 2006). Furthermore, indigenous-led initiatives centered on community-based conservation and natural resource management have demonstrated the resilience of indigenous knowledge in the face of environmental challenges exacerbated by climate change, deforestation, and industrial pollution. By prioritizing indigenous knowledge and participatory governance, these initiatives have not only yielded tangible results in mitigating ecological crises, but also empowered local communities to reclaim agency and legitimacy over their practice, heritage, and self-determination (Sillitoe, 1999).

Nevertheless, despite these reflections and the recognition of indigenous values, indigenous peoples continue to face threats to their land rights, ranging from land grabbing and resource extraction to state-sanctioned violence. The legacy of colonialism lingers on, perpetuating systems of repression that undermine the sovereignty and self-determination of indigenous groups. To deny and subvert the hegemony of colonial power and to resist land appropriation and cultural assimilation, indigenous peoples have persisted in their fight for self-determination by employing various strategies, ranging from grassroots acts of resistance and legal battles to cultural revitalization and international campaigns. In defending their rights to territories, the meaning of land is framed by indigenous activists as the life of the people nurtured by it. In this context, the significance of land in providing a source of livelihood and as the base upon which culture and identity are grounded has been continuously reiterated to highlight the sentiment of “land is life” narratives.

Diversifying the Narratives of Indigenous Experiences

The struggles of indigenous groups embody a broader quest for environmental justice and self-determination that resonates with global movements to secure the rights of indigenous peoples and marginalized communities. Transnational networks and alliances have been mobilized among indigenous societies who share similar grievances and struggles. Allying with environmental activists and human rights defenders, their voices are amplified to demand justice and accountability from governments, corporations, and international institutions. Through solidarity, indigenous activism seeks to consolidate the power of indigenous groups globally to challenge existing power structures, reshape dominant narratives, and envision alternative futures. In the struggle for self-determination, indigenous activism is characterized by a strategic appropriation of traditional elements, including the concept of land, which are essentialized and transformed into forms and language to negotiate space for indigenous knowledge within mainstream discourses (Contreras, 2011; Zamarrón, 2009). Although the strategy of essentialization helps to negotiate the power of indigenous knowledge, issues and challenges persist regarding its application.

The first issue lies in essentialization, which often imposes indigenous knowledge into Western frameworks, inadvertently reinforcing the very ideologies that indigenous discourse challenges. Secondly, a debate persists on whether a centralized theory of action should be developed to significantly impact global development discourse (Contreras, 2011). The emergence of pan-ethnic organizations under the identity of ‘indigenous people’ enables diverse groups to unite around common issues within global indigenous movements. However, the levels of political mobilization and economic development among indigenous groups vary widely across countries and regions (Levi & Maybury-Lewis, 2012). Economic and power disparities exist not only between but also within indigenous groups, a factor often overlooked in studies that tend to view indigenous people as collective entities rather than individuals (Levi & Maybury-Lewis, 2012).

Indigenous ideology is frequently portrayed as egalitarian, spiritual, and environmentally conscious, resisting capitalist influence based on notions of culture or identity (Levi & Maybury-Lewis, 2012). As discussed above, central to the discourse of the global indigenous movement is the narrative of “land is life”, which emphasizes the cultural, social, and economic significance of land. However, this discourse is not dominant among the ethnic nationalities along the Thai-Myanmar border. Here, refugee and migrant communities who voluntarily or involuntarily leave their motherland underscore the nuanced realities of indigenous resistance and negotiation in the face of economic, political, and development pressures. Does relocation offer the best means to security and opportunity? While many flee to the Thai side for a relatively secure life, others remain in their villages amid danger to be free, to maintain ties to their native land, and to carry on farming for livelihood security (Tangseefa, 2006). Even when values and practices are shared among indigenous groups, their desires and visions are heterogeneous, making a single discourse that represents a unified “people’s perspective” elusive.

As an activist for indigenous rights embedded in the “land is life” discourse for the past twenty years, the 47th Southeast Asia Seminar from the Thai-Myanmar border reminded me again of the need to probe the diverse meanings of land among people in border regions. A deeper examination of the significance of land to ethnic migrants and refugees, and of how land intersects with issues of political violence, migration, displacement, and resilience, will enhance our understanding of the varied relationships that people have with land. By listening to the diverse voices and experiences of people at the nexus of these intersecting dynamics, we can glean invaluable insights into the profound ways in which land shapes identity, sense of belonging, and well-being across generations. As we navigate the complexities of indigenous experiences in the contemporary time, it is imperative that we center the voices and experiences of the people whose lives are intertwined with the different kinds of land and places they live in, learning from their stories of struggle, resilience, adaptation, and belonging amidst the political and socio-economic challenges they face. Only through such a nuanced understanding can we provide more inclusive accounts of the realities experienced by marginalized people and gather support and empathy for their struggles in a more honest way.

Yi-Chin Wu

National Normal Taiwan University

Notes:

- While this article uses ‘refugee’ and ‘camp’ to describe individuals forcibly displaced from Myanmar and their settlements along the Thai-Myanmar border, it is worth noting that Thai officials deliberately refrain from using these terms. With no established legal framework for determining refugee status, the Thai government categorises these individuals as ‘people fleeing fighting’ and designates the settlements as ‘temporary shelter areas’ (Tangseefa, 2007; Tangseefa, 2019). ↩