Malaysia has gone through a long process of democratisation with two of the biggest social movements in its last twenty years – the 1998’s Reformasi movement and the series of demonstrations fight for free and fair election called BERSIH (2007-2016) – which enabled Malaysia to end the longest single-party state in the history of electoral democracy in the world, Barisan Nasional (BN, National Front, known as the Alliance before 1973) in the 14th General Election (GE-14) in 2018. Regime change through these elections is partly contributed by some of the common factors as in other countries that experience similar competitive authoritarian regimes (Croissant, 2022; Levitsky & Way, 2010). Simultaneously, the factors of social transformation – industrialisation and urbanisation – that contribute to the formation of the middle class and the democratisation of information through social media are also said to be among the main factors that make this political change possible. In fact, in the case of Malaysia, social media is said to be one of the main factors that enable this democratisation to happen (Haris Zuan, 2020b, 2020a).

However, since the defeat of BN in 2018, racial campaigns have been spread on social media such as Facebook and Tik Tok, leading to the mobilisation of massive street demonstrations led by Malay-Muslim conservative groups. This series of campaigns on social media was then translated in GE-15 when 89% of the Malay-Muslim popular vote went in favour of the Perikatan Nasional (PN), a right-wing conservative coalition dominated by the Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS) and The Malaysian United Indigenous Party (BERSATU). Even though the Pakatan Harapan coalition and Reformasi leader, Anwar Ibrahim was finally installed as Prime Minister – after 24 years the Reformasi movement started – social media, especially Tik Tok which is dominated by the youth, is filled with racially-motivated videos.

This led to a question, why is social media, which was initially said to be one of the instruments for political change, now associated with a regressive conservative right-wing racist campaign? Does social media in Malaysia have different effects on different demographics, especially the youth? How can we understand the role and limitations of social media as an instrument of political change in a state in transition like Malaysia?

Social Media and Democratisation in Malaysia

Malaysia has one of the highest Internet penetration rates in the Southeast Asian, with 89.6% of its 32.98 million population having access to the Internet. In context, in 1999, the Internet penetration rate was only 12%, then increased to 56% (2008), 66% (2012) and 81% (2018). The use of social media is also increasing rapidly. According to several different statistics published in 2022, a total of 30.25 million (91.7%) Malaysians are active social media users with Facebook (88.7%), Instagram (79.3%) and TikTok (53.8%) as their main social media applications. In terms of communication software, WhatsApp (93.2%), Telegram (66.3%) and Facebook Messenger (61.6%) outperformed other similar platforms.

In the last twenty years, especially after 2008, social media in Malaysia is said to be one of the important mediums that enable political change in Malaysia. Social media is a stronghold of progressive anti-establishment pro-opposition groups so that the mainstream media is gradually losing its influence as the main source of information among Malaysians, especially among the youth who are the largest demographic of this social media (Azizuddin 2014; Haris Zuan, 2014).

This was realised by the ruling party, BN especially after nearly defeated in GE-12 (2008). Therefore, to face the next GE, Najib Razak who was in his first time to lead BN into election, give a strong focus on social media to the point of mentioning GE-13 is the Malaysia’s first social media election. Najib Razak was active on Facebook and Twitter with millions of followers – so much so that at one time Najib was ranked at number 15 among the most followed government leaders in the world on Twitter. Although there are reports that say between 50-70% of his followers are fake (Haris Zuan, 2014).

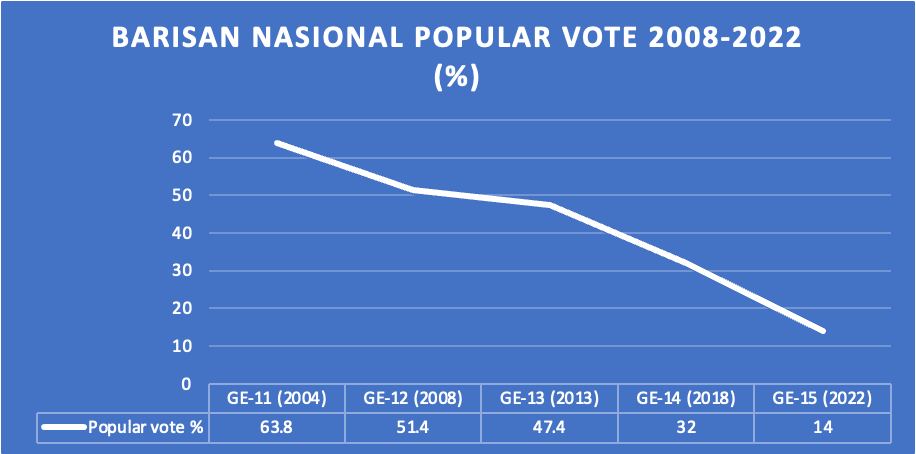

However, even though BN at that time spent millions of dollars in the GE-13 campaign, the BN huge investment in social media failed to translate into vote. BN recorded even worse results compared to the previous GE. Based on this trend, the Malay voter segment, which is said to be conservative and non-progressive, since 2008 has consistently rejected the main component party of BN, UMNO which is central in the Malay political culture to the point of being considered as ‘the protector’ of the Malays. In 2022 election, the former long serving, and two-time Prime Minister’s Dr. Mahathir, who was a hegemonic figure the Malay politics, was not only lost in the last election, but also lost his deposit too – after fail to obtain at least 12.5% of the total votes. This is something that was unimaginable 20 years ago.

Secondly, despite all the racist propaganda that arose, Malaysia witnessed a relatively smooth and peaceful government transition. Not many third world and Southeast Asian countries are able to claim this. And thirdly, there are clear indications that the public discourse of institutional reform related to anti-corruption, integrity and good governance is growing in Malaysia. Hence, it is not surprising that even PN central their campaign on clean government and despite all the rhetoric of Islamic law, Hudud, in Malaysia, PN does not mention the word hudud in their manifesto.

Another interesting development can be observed when COVID-19 hit the world at the early of 2020. Malaysia, like other countries, was also affected by the movement restrictions when members of the community were cut off from food supplies. An ad hoc, spontaneous and grassroot youth-led movement across race and religion emerged on social media with the hashtags #KitaJagaKita (looking out for each other) and #BenderaPutih (white flag) to coordinate aid initiatives for affected community members. Through this campaign, those who need help can inform others on social media of the help they need and those who can help can contact those people. The campaign quickly went viral and later that year became a dissent platform criticising government’s failure in managing the pandemic.

All these online campaigns that are ad hoc, spontaneous, issue and event-based are part of the characteristics of the new social movement. This movement is no longer define by a rigid ideology with specific social class such as the working class or labour. These movements emphasise on democratic rights and social/political representation/identities which core in active citizenship concept (Haris Zuan, 2021). These highlighted an important feature of social media in Malaysia which is having a critical relationship with the power so that it allows social media to become one of the instruments for political change in Malaysia. Now relatively, democracy in Malaysia is getting better compared to 20 years ago. In fact, Malaysia ranked top among countries in Southeast Asia and in 2021 Malaysia ranked sixth in the Asia and Australasia region, and 39th globally (source: The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2016-2021.

Then, if the democratisation situation in Malaysia is getting better, how to explain the mass media reports and politicians’ claims that describe the resurgence of religious ethno-nationalist sentiments in Malaysia?

Limitations and challenges of social media as an instrument for political change

In general, social media is growing rapidly and becoming more dynamic – evolved from simple text-based communication to multimedia content sharing. In Malaysia, social media, especially Facebook helps diminish the state’s control over information that led to democratisation of information. However, with the emergence of more micro blogs such as Twitter and now short-video based platform, Tik Tok, the role of social media as a rational and constructive in-depth discussion medium is becoming increasingly challenging – due to the nature of social media itself becoming volatile with information overload that contribute to misinformation and disinformation. Still, the evolution of social media itself is not the main challenge to enable it to become an instrument of change in Malaysia case.

Social media is only part of the public space and in the case of Malaysia, it is difficult for a counter discourse to succeed if it depends solely on social media when other public spaces are dominated by a more dominant discourse. Thus, counter discourse must also take place in other physical public spaces.

One of the best examples is Fahmi Reza, a celebrated political graphic artist who ran an electorate education campaign for youth during the GE-15 campaign. His campaign started on Tik Tok and then despite getting a lot of interaction, he consistently tried to hold his political education classes on university campuses across the country – despite been barred from almost all campuses by university authorities. However, not many progressive groups are able to take their campaigns out of this social media space (Mohd Izzuddin Ramli & Haris Zuan, 2018). Worse, there is a tendency for political parties to ride and take advantage of the popularity of online campaigns. For example, the #KitaJagaKita campaign which was later ridden by the opposition party as a platform to condemn the government – without meaningful contribution to the campaign.

This is different from right-wing conservative groups that have strong present in other public spaces such as schools, universities, and mosques. In Malaysia, only PAS has the most extensive political education and cadre system among the youth. PAS is not only a political party but also conducts many other activities such as preaching, running educational institutions from pre-school to secondary, and volunteering activities. This makes PAS very influential among Malay youth (Haris Zuan, 2018).

The relationship built by PAS goes beyond mere electoral politics and engagement through social media is certainly far from sufficient to gain the trust of these young voters. So, when PAS in 2015 left the loose coalition of the opposition at the time, Pakatan Rakyat, the void in the public sphere could not be filled quickly. PKR and DAP have created a special program, political education for young voters, but this program is too small and too short. In fact, this program was discontinued by PKR and DAP after the victory in GE-14. PH and newly established youth-based political party, MUDA (literally translated as young) that successfully translated their GE-14 manifesto to lowering the minimum voting age from 21 to 18 years old in 2019 Constitution amendment seem lost how to mobilise the youth support.

Tik Tok’s demographics in Malaysia are mostly Gen Z and Millennials under the age of 24 who are not from the 1998 Reformasi or 2008 BERSIH generations – two social movements that form the collective memory – making them have no attachment to this movements neither to the Pakatan Rakyat (PR) or Pakatan Harapan (PH). This Tik Tok generation is the one who sees PR/PH as part of those in power (ruling the two richest states in Malaysia since 2008 before becoming the federal government in 2018) – not a part of social movement representing the people. While this can make them critical to both side but also make them reject both sides too.

Apart from challenges from the ‘intrusion’ of government and political parties, the autonomy of social media as an instrument of political change is also challenged by the influence of consumerism. This trend is not new and can be traced since the emergence of globalisation since the late 1990s. But with the development of e-commerce platforms that are embedded in social media, consumerism has reached a new level especially among the youth that has tendency to make them politically apathy.

Conclusion

Malaysia is faced with the dilemma of the need to build a stable and functional government that upload the freedom of expressions but is heavily attacked by right-wing conservative groups on social media. Since restricting social media is no longer an option for the government that promoting structural reforms, they should continuously engage with the people on and off social media constructively. Civil society should support this effort to fight misinformation and disinformation by empowering the citizens, especially youth with the ability to manage information. Only through an educated citizens (and netizens) will democracy work.

Haris Zuan

Institute of Malaysian & International Studies (IKMAS)

National University of Malaysia (UKM)

References

Azizuddin, M. Sani. (2014). The Social Media Election in Malaysia: The 13th General Election in 2013. Kajian Malaysia: Journal of Malaysian Studies, 32.

Croissant, A. (2022). Malaysia: Competitive Authoritarianism in a Plural Society. In: Comparative Politics of Southeast Asia. Springer Texts in Political Science and International Relations. Springer, Cham.

Haris Zuan. 2021. The Emergence of a New Social Movement in Malaysia: A Case Study of Malaysian Youth Activism. In: Ibrahim Z., Richards G., King V.T. (eds) Discourses, Agency and Identity in Malaysia. Asia in Transition, vol 13. Springer, Singapore.

Haris Zuan (2020a) ‘Youth in the Politics of Transition in Malaysia’, in Towards a New Malaysia?. NUS Press, pp. 131–148.

Haris Zuan (2020b) Transformasi Sosial dan Politik Belia Menelusuri Perubahan Budaya Politik Belia di Malaysia. Bangi: Penerbit UKM.

Haris Zuan (2018) Bersediakah Malaysia turunkan umur mengundi?[ Is Malaysia ready to lower the voting age]. Malaysiakini. https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/443829

Haris Zuan (2014) ‘Pilihan Raya Umum Ke-13: Perubahan Budaya Politik Malaysia Dan Krisis Legitimasi Moral Barisan Nasional [The 13th General Elections: Changes In Malaysian Political Culture And Barisan Nasional’s Crisis Of Moral Legitimacy]’, Kajian Malaysia, 32(2), pp. 149–169.

Levitsky, S., & Way, L. (2010). Competitive authoritarianism: Hybrid regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge University Press.

Mohd Izzuddin Ramli & Haris Zuan. 2018. ‘Cartoons and Graphic Arts: Resistance and Dissidence Within and Beyond Electoral Politics’ in James Gomez, Mustafa K. Anuar, and Yuen Beng Lee (eds.) Media and Elections Democratic Transition in Malaysia. SIRD: Petaling Jaya

The Economist Intelligence Unit (2016-2021). Democracy Index. https://www.eiu.com/