A New Beginning

As of now, the world has been plagued by a new infectious disease caused by a new strain of coronavirus known as COVID-19. First detected on the 17th of November 2019 in Wuhan, China, it has spread globally without mercy. In Malaysia, the first case of COVID-19 was discovered by authorities on the 25th of January 2020. As a preventive measure to control pandemic in the country, Malaysian Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin introduced the Movement Control Order (MCO) on 18 March 2020. Until now, the MCO has taken various forms and authoritative levels depending on the severity of cases reported in certain regions in Malaysia. This directive has been complied by a multitude of state/non-state actors and agencies including the education sector – schools, vocational college, government and private universities.

Digital Pedagogy

In the early stages of the MCO, university students were instructed by the Ministry of Higher Education to return to their respective hometowns. Initially, some complications occurred during the process due to the joint efforts of parties involved, namely the Ministry of Higher Education itself, university authorities and the police officers on duty, as the circulation of information and instructions were quite unstructured. Eventually, a fruitful bottom-to-top collaboration within the university’s managerial sectors, namely faculty and residential college staff, managed to ease the process. Although the safety of students was assured, more pressing matters regarding pedagogical approaches arise.

The implementation of the new university curricular in the midst of COVID-19 needs to be altered in adapting to factors such as; teaching methods during lectures or tutorials, assignment, final assessments, and the dialogic process between lecturers and students, as well as the mental and psychological state of stakeholders involved during the teaching and learning activities.

Most universities implemented Open and Distance Learning (ODL) as a new mechanism to execute learning processes throughout the duration of the MCO. The ODL system can be achieved without the normal consideration of temporal and spatial limitations. Comprised of two categories which blend through asynchronous (without real-time interaction) and synchronous (with real-time interaction) approaches, ODL is perhaps one of the best and timely solutions to shift from traditional pedagogical methods towards digital pedagogy, especially considering the urgency in this crucial time. Instead of using a typical classroom setting and face-to-face interactions, lecturers and students are still able to communicate with each other, mediated by digital platforms. Since the ODL is rarely practiced, the implementation of new methods must come with careful planning. A close consideration of students’ experiences with ODL must be viewed as a prime factor in adjusting to the most adequate alternative pedagogical mechanism.

In principle, the transition in shifting towards a newly-introduced digital pedagogy through the method of ODL requires three phases. The first phase is the planning stage, where lecturers need to source information from the stakeholders involved in the learning processes, namely the students, fellow academic colleagues, as well as the faculty and university managerial staff. The obtained data will enable a suitable design of the ODL mechanism in adapting to certain constraints, while also considering more beneficial approaches in learning processes. Some factors to consider are the total number of students and student capacity for each class/subject, the form of learning curve required for specific subjects, methods of assignments and final assessments, and especially the students’ capacity and accessibility to the internet.

The effectiveness of digital platforms should be tested first. Only then, the syllabus can be adjusted to suit the alternative pedagogy. For example, Google reprogrammed their video conferencing and streaming application, Google Meet, to expand the limit of participants to 250 users in a single meeting (this feature was discontinued by Google on the 30th of September 2020). In addition, lecturers could opt to record and upload their video lectures on YouTube or Facebook, to ease the burden of internet accessibility.

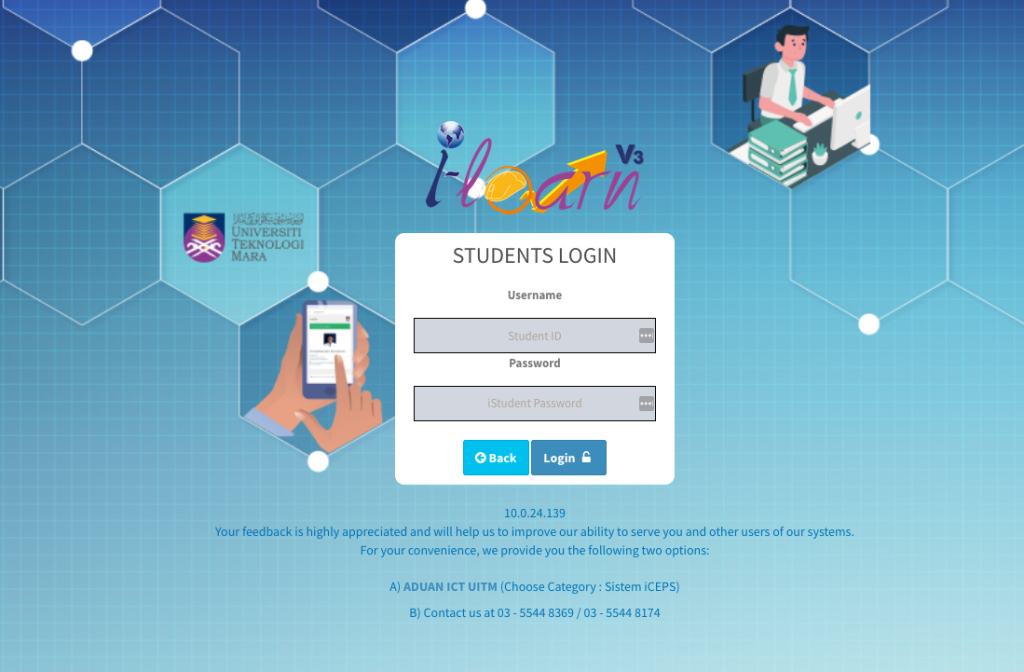

Some Malaysian universities have their own Moodle-like Learning Management Systems (LMS). For instance, UiTM has an easy-to-use and accessible online platform called i-Learn and UFuture which were developed for digital learning activities. Nonetheless, even with the specialized platforms, WhatsApp is deemed the most accessible platform to communicate due to its text-based architecture.

The next phase is the implementation stage. In this phase, lecturers need to constantly monitor their delivery of ODL while consistently keeping track of their students’ learning experience. If the current mechanism does not fulfill optimum benefit to the overall process of teaching and learning, it should be adjusted. The last phase is the outcome stage, where an assessment of the effectiveness of ODL should be done to make room for adjustments and better equip the learning experience.

In my experience as a lecturer, ODL started off as a breeze. Along the way, there were a few setbacks, but they were part and parcel for all parties involved – lecturers and students, in adjusting to the new norm. However, eventually, students started to appear tired and distressed with classes through video conferences, as some still had trouble adjusting to the shift of learning mediums. Some students complained that they were not able to focus while they had to sit for classes on their mobile screens in their own homes; some were burdened by domestic obligations. A number of students prefer face-to-face communication with their lecturers as it enables authentic conversations to better learn the subjects, in the event of any confusion or need for clarity. On the other hand, language became a barrier for some students. In the case of lecturers who are required – as is sometimes their preference – to give lectures in English, some students have difficulty with the language.

From hearing my students’ opinions on the turbulent transition to digital mediums, it dawned on me to ensure the success of ODL beyond the means of the internet connection dilemma. After all, this scenario is nothing peculiar (even during this unprecedented pandemic), as experienced educators should have expected it.

But, strange things happened.

Some of those in academia opined that the problems regarding ODL comes solely from the students’ temperament, as they rely too much on being spoon-fed and are often inattentive. According to these individuals, students do not recognize the need for themselves to reciprocate. They are irresponsive during online classes – often times, little to no feedback is given during the entire teaching and learning process. Ultimately, from this perspective, this multi-dimensional and layered issue boils down to individual responsibility.

Neoliberalism in Malaysian Higher Education and Individual Responsibility

To reflect on the above statement, we should trace the underlying philosophical paradigm of the Malaysian higher education system. Since the inception of the University of Malaya (UM) as the first national university in 1949, Malaysian higher education rapidly progressed as some of the universities strove to climb the global ranking. Thanks to the Private Higher Education Institutions Act 1996 (Act 5), private university numbers boomed.

Soon, the concept of university began to change. Instead of becoming the paragon of knowledge and truth, it slowly become a corporate behemoth – churning out graduates for tidy profits. Universities are no longer run by scholars but by bureaucrats. This phenomenon of neoliberalisation of higher education have changed the way we see education as it supposed to be – to bridge the gap of knowledge between those sitting in the ivory tower and society.

But more on that, in terms of public discourse, neoliberalism normalizes us to think that societal problems are the responsibility of every citizen. It is not systemic and it is not under the purview of the government.

Remembering two years ago when I first entered a local university as a lecturer, I had a brief discussion with my students about the idea of bringing back Pengajaran dan Pembelajaran Sains dan Matematik Dalam Bahasa Inggeris (PPSMI), translated as Teaching and Learning Science and Mathematics in English during our textual analysis class. PPSMI is a government policy introduced by the then Prime Minister, Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad to improve primary and secondary school students’ English proficiency. Two of my students who are conversant in English argued that all students should give their own effort to master the language regardless of their social capital. However, their view is positioned under the schemata of neoliberalism, as it stresses on the individual responsibility instead of placing the onus on the government or civil society.

Recent complaints from some lecturers regarding their students’ performance convinces me that any problems concerning ODL; the delivery of lessons, students’ ability to grasp the knowledge taught during lectures or tutorials, including the problematic attitudes of students in online classes, cannot be viewed simply under the notion of individual responsibility.

I would argue that despite the availability of these digital platforms which appear liberating, and enunciate surplus space to its users, paradoxically, they limit and compress space.

Compression of Space

When ODL was going to be implemented by the university managements, most discourse of ODL in Malaysia centered around the idea of internet connectivity. In this regard, we have an assumption that if we somehow manage to tackle and provide a good or efficient internet access to the students, everything (or most things) will go well.

When we talk about online learning, I think we ought to see a different perspective as well, in this case, a perspective of space. The availability of the space and how this space is (re)configured need to be examined. But what is most crucial is to realize that every time ODL took place, there is an overlapping of different type of spaces (and we are not talking about physical space only).

Public space, private space, social space, study space; all overlap with each other. Here, there is no clear demarcation of space between them. Although ODL can be considered as a flexible learning mechanism, which can be occur asynchronously or synchronously, but the online learning experience is not as organic as learning in a physical classroom. In the physical classroom, the pattern and usage of space and time is clearly visible and embodied by every student. The learning and teaching process for each subject can be phenomenologically felt.

However, through ODL, this demarcation seems blurred. When students study online at their respective homes, not only their spaces are being overlapped, but also their role. At home, a university student is no longer just a university student. They are required to assume various other roles and responsibilities as a son or daughter, sister or brother, neighbor or role model to their society. This of course would put extra and unnecessary burdens on women because of the domestic responsibilities that are often associated with the role of conventional gender in a patriarchal society such as Malaysia.

All these situations that I have mentioned should also be analyzed together with the social capital of the student. Students come from various backgrounds, disparate economic structures, diverse life experiences and ideologies, which are shaped by experiences and ideologies while they are in a particular institution including higher learning establishments.

I think while it is vital for us to ensure that ODL runs efficiently and achieves its goals, we must also take into account the question of space articulation and role ambiguity which of course has an impact on every student who experiences online learning.

Rather than we perceiving this digital pedagogy as a bureaucratic labor, it is highly productive for us to observe a more humanistic approach. Indeed, that is the imperative duty of the university and the responsibility of the true scholars.

Mohd Sazni Ahmad Salehudin

Mohd Sazni Ahmad Salehudin’s field of study is in Industrial Psychology and his research interests explore into the arts and humanities through inter-disciplinary practices of social sciences equipped with psychology as a solid starting point. As a lecturer at the Faculty of Film Theatre and Animation (FiTA), Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), he has refined his understanding on the key concepts and theories of the arts and humanities. At FiTA, he’s teaching three subjects which are Philosophy of the Arts, Textual Analysis and Criticism and Great Literature. He is currently writing a study focused on the digital identity and the development of digital sociology as a new discipline in Malaysia for Projek Penyelidikan Naratif Malaysia, a research project under the Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM).