It would not be an exaggeration to say that the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the greatest online learning experiment at a global scale. As a result of campus closures, teaching and learning activities are either suspended or moved online. In Singapore, face-to-face (FtF) classes at all levels of learning are suspended throughout the period the government referred to as Circuit Breaker, from 8 April 2020 to 1 June 2020.

This short essay contains my personal reflection as an Instructor teaching Academic English and Public Policy Communications at a leading graduate school of public policy in Singapore, covering the period from April 2020 till the present:

| Phase 1 (8 April – 9 May 2020) | Emergency online teaching |

| Phase 2 (10 May – 2 August 2020) | Reflection and planning ahead |

| Phase 3 (3 August – present) | Teaching in the “new normal” environment |

The Context of My Teaching

I provide Academic Language and Learning (ALL) support to enrolled students by teaching semester-long, non-credit bearing Academic English classes and standalone lunchtime workshops covering different aspects of Public Policy Communications such as writing policy memos, policy briefs, op-eds and presenting to stakeholders. The constructivist approach, which views learning as “knowledge creation within individual minds and through social activity” (Cross, 2009, p. 31), is especially pertinent in my teaching. Students bring a wealth of diverse policymaking and administrative experiences to classroom discussions on various issues in public policy communications. Effective teaching and learning in my context, then, require frequent, robust and immersive meaningful communication, feedback and interaction:

- between the teacher and the class (T-SS),

- between the teacher and an individual student (T-S),

- between individual students (S-S)

- between an individual student with student groups (S-SS)

- between student groups (SS-SS)

- between an individual student with the teacher and other students (S-T&SS)

Phase 1: Emergency Online Teaching

During the initial days of shifting to emergency online teaching, the temptation was to replicate the physical classroom in an online learning environment. Feeling the need to ensure my students were not shortchanged, I retained the full three-hour teaching sessions. I quickly realized that this was not sustainable, as the long hours led to exhaustion for both the learners and the instructor. Supiano’s (2020) reminder to not replicate FtF teaching online was thus a personally liberating message. Blog contributions by educators, such as those published on The Chronicle of Higher Education and Teaching Connections – maintained by the National University of Singapore’s Centre for Development of Teaching and Learning – were particularly edifying and provided me with useful tips as I scrambled to provide quality online teaching.

In addition to repurposing my classroom teaching materials so that they would be suitable for online delivery, the content of selected ALL materials was redesigned within a short period of time to ensure relevance in supporting students’ ALL needs in an online context. This phase of emergency online teaching took place towards the final one-third of the academic semester. For a workshop on oral presentation skills, which I typically conduct near the end of the semester, I now included new content on effective voice projection, eye contact and body language for virtual presentations. I found it necessary to update my teaching materials on Academic English and public policy communications to reflect the academic skills needs of students when switching to online learning.

During this phase, teaching support and emergency training in pedagogy – provided by either teaching excellence centers at the institutional level, or by teaching excellence committees at the departmental level – were crucial to empower instructors to better able to adjust to remote teaching. While the availability and use of educational technology are not new, studies have shown that many university instructors do not necessarily have the relevant pedagogical skills and knowledge in delivering online education effectively (Wiesenberg & Stacey, 2005; Cross & Polk, 2018; Vallade & Kaufmann, 2020). At my university, seven professional development sessions were offered in the first 11 days following the start of Circuit Breaker, addressing such issues as online assessments, online lecture delivery, and design of assessments that require higher order thinking skills. Teaching excellence committees within departments at the university also organized sessions to address discipline-specific pedagogical concerns.

Phase 2: Reflection and Planning Ahead

This phase refers to the vacation period between May and August 2020. With the semester officially over but the COVID-19 pandemic showing no sign of abatement, it became increasingly likely the new academic year would begin with modules delivered fully online, and thus a systematic rethinking of effective online pedagogy was necessary during this phase. The question “How can we, in the formal, guided process of higher education, use the power and potential of recent electronic media to enable our students to learn better, from us, from each other and independently?” (Brenton, 2009, p. 85) formed the overarching question as I both reflected on my experience in Phase 1 and planned for the upcoming academic year. While most pedagogical decisions in Phase 1 were aimed as mitigation, the conscious thinking of an effective online pedagogy and purposeful redesign of curriculum were now necessary. The use of educational technology must be intentional to promote active learning and encourage interaction between the student and the instructor (“from us”), among students (“from each other”) and facilitate critical self-reflection (“independently”).

I decided to use Hypothesis, an online annotation tool, as a means to encourage the types of interaction mentioned above. During this phase, I curated a set of pre-workshop readings consisting of actual policy documents that could be used effectively with Hypothesis to teach different aspects of writing and public policy communication. My plan was to adopt Hypothesis to encourage both synchronous and asynchronous discussions: students could highlight specific texts directly online or on the PDF document and post their own annotations and replies to others’ comments before, during and after a live class/workshop session. Students could choose which annotations to be shared with other class members or which ones to be set private, if they are meant for personal reference or self-reflection. Separate private groups could also be created in Hypothesis for group discussions.

I have found that peer support within the context of communities of practice, in addition to continuous professional development through workshop attendance, particularly helpful in developing my teaching repertoire. During the summer months, I participated in a number of Open Conversation sessions and am greatly encouraged by the discussions among peer educators. These Open Conversations sessions not only provided me an opportunity to reflect more deeply on my teaching practice, but also acted as a platform for peer educators to share best teaching practices, especially with regard to the effective use of educational technology in facilitating teaching and learning. Research has shown the efficacy of communities of practice in professional development among university instructors (Blanton & Stylianou, 2009), and encouraging intentional dialogues among peer educators can be particularly helpful, in my opinion, as educators navigate the unfamiliar territory of teaching during an era of pandemic.

I have found that peer support within the context of communities of practice, in addition to continuous professional development through workshop attendance, particularly helpful in developing my teaching repertoire. During the summer months, I participated in a number of Open Conversation sessions and am greatly encouraged by the discussions among peer educators. These Open Conversations sessions not only provided me an opportunity to reflect more deeply on my teaching practice, but also acted as a platform for peer educators to share best teaching practices, especially with regard to the effective use of educational technology in facilitating teaching and learning. Research has shown the efficacy of communities of practice in professional development among university instructors (Blanton & Stylianou, 2009), and encouraging intentional dialogues among peer educators can be particularly helpful, in my opinion, as educators navigate the unfamiliar territory of teaching during an era of pandemic.

One important lesson regarding online teaching that I have learnt from these peer conversations is that instructors must be selective in the adoption of educational technology. Not only should the design and use of educational technology be in such a way that promotes actual learning and not impose extraneous cognitive load that distracts from learning (Sweller, 1994), instructors should also limit the number of technological tools to be employed in one’s module, so that students will not be overburdened with learning how to use different tools and software for different modules.

Phase 3: Teaching in the “New Normal”

My experience with the Flipped Classroom method has not been as encouraging as the positive experiences that have been variously documented. The two workshops that I conducted during Orientation Week this year – on Academic Writing Conventions and Writing Policy Memos – followed a two-part format where students were asked to study a series of short video presentations (each approximately six minutes in length, with embedded quizzes) before attending a live one-hour webinar on Zoom. Video analytics showed that student engagement with the online material was low, with only about 31 per cent of students having perused the multimedia material prior to the live session. Perhaps a follow-up study would be helpful in understanding this observation.

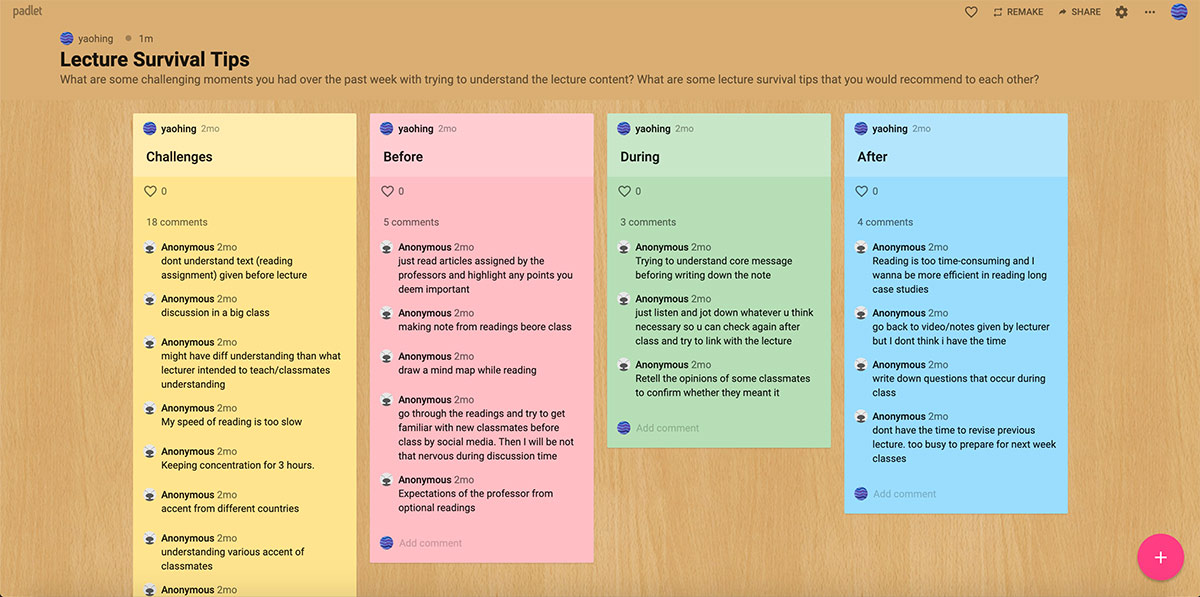

I have found the use of Hypothesis effective in promoting greater participation among students from whom English is a second (ESL)/foreign (EFL) language. The general impression among many educators is that ESL/EFL students from East Asia and Southeast Asia are generally reticent for a variety of personal and cultural factors (Campbell, 2007), and this has certainly been my experience at my present university, where East Asian and Southeast Asian students form the majority of the overall student population. An oft-cited reason by my students is that they encounter difficulty in comprehending what many of their more outspoken peers are saying due to their accents. This problem is actually exacerbated in an online classroom environment due to weak or intermittent internet connection, but ESL/EFL students have found the use of Hypothesis effective as they are now able to read (and thus comprehend) what their peers have to say. This does not mean that Hypothesis is used as a substitute for verbal communication. Rather, the written annotations and comments provide a reference point or context to aid students’ comprehension of their peers’ spoken ideas, in addition to serving as a prompt for further verbal discussions. Another tool that I have found particularly useful in fostering engaging discussions is Padlet, a virtual Post-It wall. For me, the use of appropriate online educational technology has resulted in ESL/EFL students’ increased participation and engagement in both synchronous and asynchronous discussions, thus allowing them “to learn better, from us, from each other and independently” (Brenton, 2009, p. 85).

How Then Should We Teach

Some form of computer-aided instruction might have existed at least as early as the 1960s. For instance, Brudner (1968) described the use of computers in providing individualized instruction in a school in Pittsburgh (as cited in Cody, 1973, p. 22). However, it is due to the Covid-19 pandemic that there is a concerted effort to promote online education at a global level. Instructors who may have not been – and still may not be – educational technology enthusiasts have had to utilize educational technology tools out of necessity. However, Brenton (2009) rightly cautioned that “E-learning rarely works where it is regarded as simply a value-added extension of the main part of the course” (p. 91).

The COVID-19 pandemic has truly disrupted the landscape of higher education globally. Although FtF classes at my faculty have since resumed for modules with enrolments below 50, my non-credit bearing, support classes in Public Policy Communications remain online, as most of my students are international students who remain in their respective home countries, either by choice or due to existing travel restrictions. One central idea of disruptive innovation, which Christensen introduced in 1995, is that “certain kinds of cheaper, usually inferior innovations change an industry not by serving current consumers better, but by greatly broadening the audience willing and able to consume that product or service” (Lederman, 2017). Might the COVID-19 pandemic become the defining moment that will reshape higher education? Only time will tell, but educators do need to ready themselves.

Yao Hing Wong

Yao Hing Wong is an Instructor at Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, a graduate-level autonomous school within the National University of Singapore (NUS), where he teaches English for Specific Academic Purposes (ESAP), conducts workshops on various aspects of public policy communication such as writing policy memos, writing op-eds and presenting to clients and stakeholders, and advises students on the quality of their capstone projects and master theses. Currently, Yao Hing also leads an NUS-funded Learning Community project to study pedagogical issues on teaching pre-employment and training (PET) learners and Continuing Education and Training (CET) students within the same classroom. Yao Hing has a Master of Education (Applied Linguistics) degree from University of New South Wales, Australia.

References:

Blanton, M. L., & Stylianou, D. A. (2009). Interpreting a community of practice perspective in discipline-specific professional development in higher education. Innovative Higher Education, 34(2), 79–92. doi: 10.1007/s10755-008-9094-8.

Brenton, S. (2009), “E-learning – an introduction”, in H. Fry and S. Ketteridge (Eds). A Handbook for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Enhancing Academic Practice (pp. 8598). New York, NY: Routledge.

Campbell, N. (2007). Bringing ESL students out of their shells: Enhancing participation through online discussion. Business Communication Quarterly, 70(1), 37–43. doi: 10.1177/108056990707000105.

Cody, R. (1973). Computers in education: a review. Journal of College Science Teaching, 3(1), 2228. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/42964862

Cross, S. (2009). Adult teaching and learning: Developing your practice. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

Cross, T., & Polk, L. (2018). Burn bright, not out: Tips for managing online teaching. Journal of Educators Online, 15(3). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.9743/jeo.2018.15.3.1

Lederman, D. (2017, April 28). Clay Christensen sticks with predictions of massive college closures. Inside Higher Ed. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2017/04/28/clay-christensen-sticks-predictions-massive-college-closures

Supiano, B. (2020, April 30). Why you shouldn’t try to replicate your classroom teaching online [Newsletter]. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/teaching/2020-04-30

Sweller, J. (1994). Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and Instruction, 4, 295-312.

Vallade, J. I., & Kaufmann, R. (2020). Instructor misbehavior and student outcomes: Replication and extension in the online classroom. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 117. doi: 10.1080/15391523.2020.1766389.

Wiesenberg, F., & Stacey, E. (2005). Reflections on teaching and learning online: Quality program design, delivery and support issues from a cross-global perspective. Distance Education, 26(3), 385–404. doi: 10.1080/01587910500291496.