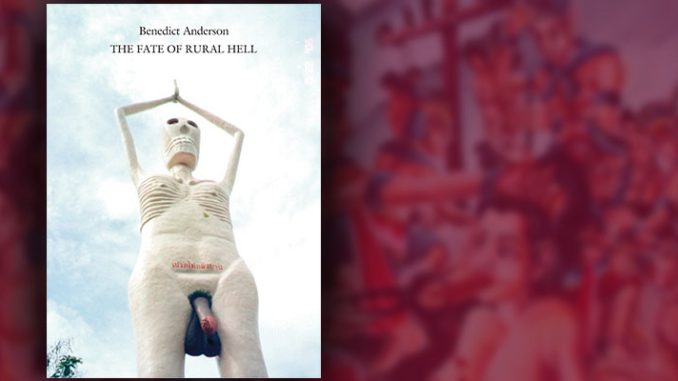

The Fate of Rural Hell: Asceticism and Desire in Buddhist Thailand.

Benedict Anderson.

Calcutta: Seagull books. 2012. 99 pp.

Luang Pho Khom’s depiction of life after death in the form of preta posting in chaotic and horrible gestures in torturing hell, which Anderson claims, ‘lies between the monkhood and working rural families.’ In these ‘all very local’ illustrations of worldly sin, Luang Pho Khom was the one who came up with the ideas of what kinds of deed are considered indulgent and how the merciless consequences of transgressions of such deeds should be depicted in his abhorrent hell. It is clear to Anderson that the abbot’s plan was to send out a strong message to the visitors of the kinds of actions that should be prohibited and avoided and, to a larger extent, how ‘a sound (rural) social order should exist.’ Along with the pictorial depictions of the dreadful preta taken by the author and his colleagues, the book also emphasizes the need to look into the rationale behind each figure. It also focuses on how these depictions reflect the burning concerns of the loss of rural morality amidst the transformation into a materially-oriented modernity at the time the figures were constructed.

Luang Pho Khom’s depiction of life after death in the form of preta posting in chaotic and horrible gestures in torturing hell, which Anderson claims, ‘lies between the monkhood and working rural families.’ In these ‘all very local’ illustrations of worldly sin, Luang Pho Khom was the one who came up with the ideas of what kinds of deed are considered indulgent and how the merciless consequences of transgressions of such deeds should be depicted in his abhorrent hell. It is clear to Anderson that the abbot’s plan was to send out a strong message to the visitors of the kinds of actions that should be prohibited and avoided and, to a larger extent, how ‘a sound (rural) social order should exist.’ Along with the pictorial depictions of the dreadful preta taken by the author and his colleagues, the book also emphasizes the need to look into the rationale behind each figure. It also focuses on how these depictions reflect the burning concerns of the loss of rural morality amidst the transformation into a materially-oriented modernity at the time the figures were constructed.

In Anderson’s portrayal of Luang Pho Khom’s biography, it is undeniable that the abbot is unmistakably a man of ambition. He was born in 1902 into a peasant family in a remote and sparsely populated village in Suphanburi province. He grew up during the transitional period in the reigns of Kings Rama V and VI. The young boy started his basic education at a local school while staying at a local temple learning the Khmer language and Buddhist discipline. He was sent to Bangkok for higher, more state-controlled education and returned home upon finishing his primary school. At the age of twenty, he was ordained and somehow placed at the underdeveloped Wat Phai Rong Wua but then he left after a brief stay for another phase of education. When he returned to the wat and became an abbot, Luang Pho Khom started to build a sermon hall, a temple school, and a central sanctuary. Later on he orchestrated the construction of a record-breaking Buddha statue in his rural temple. This was possible with the modern construction technology available, the easy income from selling amulets during the craze developed by urban people seeking for spiritual materials, the unpaid ‘pre-capitalist’ kind of temple labour, the support from the state, as well as his opportunities to travel abroad and learn more about the wider world. The plan was achieved and King Rama IX had to travel by helicopter in those days in order to inaugurate the official opening of the statue to the public. The abbot, as Anderson suggests, even predicted that his remote temple one day would become a business hub of the country.

The development and persistence of the wat before and after the death of Luang Pho Khom reflect the living legend of rural struggle and challenge us to reconsider what we understand today as Thailand’s “rurality.” The energetic life of Luang Pho Khom is a fine illustration that suggests the aspiration of rural people and their desires for the betterment of their own lives. Monkhood, schooling, traveling, the exploitation of rural cheap labour, and the engaging of oneself with capitalists and “big people” in politics as reflected in the course of the abbot’s life are all the rural strategies to become aspired in the modernized Thailand during the past decade. Besides the ambitious life of the revered abbot, in the temple, too, the juxtaposition of many distinctive religious figures, edifices and symbolic representations from both local and non-local world together in one place has enabled Wat Phai Rong Wua to literally become a sanctuary of power where multiple authorities of good deeds and benevolent powers can join hands and create an even more sacred and mysterious sphere for their creator. This juxtaposition of multiple powers into one place, however, is not particular to the wat. In fact, the modern rural community is a productive space where rural villagers always engage and bring in multiple authorities—the state, capitalists, NGOs, local powers, tourists, politicians, monks, and even supernatural entities—to create a place where they can manipulate the network of powers for their own benefits. The temple, like the rural community, is thus a reflection of the unclear distinction between the local, national and the international features which conveniently coexist within the rural lives.

Anderson’s latest book The Fate of Rural Hell is a crucial manifestation of not only how the life and death in Buddhist teaching is perceived and recreated but also illustration of the dynamism—the fates and the faiths—of rural livelihood, the context in which the striving creation of this impressive wat came into existence. It is a fine book, to be read not only its insights into the life and death of the rural people, but also the pathways between them. It is indeed what I see as “the hail of rural faith” through a close look of the fate of rural hell.

Reviewed by Jakkrit Sangkhamanee

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 12 (September 2012). The Living and the Dead