With the victory of Donald Trump in the 2016 US presidential election, followed by the increasing influence of right-wing political parties in Europe, it has become fashionable to use populism as a way to understand politics—especially electoral politics. Indeed, populism as a concept is not a new one; it has been discussed in many parts of the world, such as South America, the United States, Europe, and even Asia. With this increasing trend toward populism, mainly in the United States and Europe, there is a strong temptation to explain political dynamics using this concept, including in Indonesia.

This paper searches for a better approach to understanding electoral politics in Indonesia. It contends that it would be better to understand electoral political dynamics by looking at identity politics. Identity politics refers to religion (Islam). This study also considers the limits of populism in understanding electoral politics.

On Populism

There are various definitions of populism, with scholars underlining different dimensions of it. It would also be safe to claim that populism is a contentious concept. For example, Steven Levitsky and James Loxton (2013, 110) highlight three characteristics of populists: “first, mobilise support via anti-establishment appeals, positioning themselves in opposition to the entire elite. Second, populists are outsiders, or individuals who rise to political prominence outside the national party system. Third, populists establish a personalistic linkage to voters.” This concept emphasizes three elements: anti-establishment, political outsider, and personal linkage of the populist leader with voters.

In a somewhat similar fashion, Kurt Weyland (2001, 14) views populism as a “political strategy through which a personalistic leader seeks or exercises government power based on direct, unmediated, uninstitutionalized support from large numbers of mostly unorganized followers.” Weyland’s concept of populism seems to be minimal compared to that of Levitsky and Loxton, as he emphasizes only the political strategy of a leader in gaining political support from voters.

Cas Mudde (2004, 543) argues that

[populism is] a thin-centered ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite,’ and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.

Mudde’s definition of populism adds a new emphasis, as he clearly divides society into two opposing groups: populists and non-populists—or, in his words, “the pure people” and “the corrupt elite.” His definition is a departure from existing concepts, which stress the primacy of leadership. However, this paper proposes that populists believe they are beyond the nation because they have the capacity to mobilize individuals by constructing the empty identifier of “people.” Following in Mudde’s footsteps, other scholars have refined the concept of populism. They claim that populism depends on how one thinks broader social groups are doing—in short, whether the rich are getting richer and the poor poorer (Rathburn et al. 2017). Based on this notion, it would be clear that populists divide society into two opposing groups.

From the short discussion above, populism can be considered to be a political stance as well as an ideology or political belief. In many places, populism has been an expression of a deep anger or frustration toward groups of people who are considered by the majority (voters) as destroying their values or economic opportunities. Populism has anti-elite, anti-establishment, anti-pluralist, anti-immigrant, and anti-politics characteristics. Based on divisions in society, populists claim that they represent the people, and other members of society who do not believe in their cause are considered enemies. Other than being an expression of anger, populism tends to create a conversation about a continuous fight between good and evil, or between the corrupt elite and the pristine people. Populists tend to simplify difficult or complex problems, and therefore they have only simple answers or solutions to every complex problem: to direct blame toward other groups of people, usually political elites or immigrants.

Populism tends to pose a danger to democracy. The idea of a single, homogeneous, authentic people is a fantasy. This is a dangerous fantasy, because populists do not just thrive on conflict and encourage polarization; they also view their political opponents as “enemies of the people” and seek to exclude them altogether (Müller 2016).

Populism in Indonesia

Discussions on populism in Indonesia mainly evaluate the 2014 presidential election and Joko Widodo’s (Jokowi’s) performance as mayor of Solo, a small town in Central Java. The analysis centers on two politicians: Prabowo and Jokowi. Most of the analyses discuss the 2014 election in which Prabowo and Jokowi competed for the presidency. For example, one scholar mentions that the latter offered a different kind of populism: he did not promise to revamp the political system, did not target any particular actor or group as the enemy, refrained from anti-foreign rhetoric, and promised to improve public service delivery (Mietzner 2015). Marcus Mietzner (2015) claims that Prabowo followed classic textbook populism: he attacked foreign companies for extracting Indonesia’s natural wealth without proper compensation; portrayed domestic elites as cronies of those foreign parasites; and appealed primarily to the poor, uneducated, and rural population. However, one should be careful with nationalist discourses existing in modern Indonesia, which also offer a similar anti-foreign and anti-elite narrative. Thus, both populist and nationalist discourses share a similar language. Sukarno employed the strategy of anti-foreign rhetoric. The question to be asked is: What makes Sukarno a populist leader but not Prabowo and Jokowi? Having invented the ideology of Marhaenism, which stresses homogeneity and gotong royong (mutual cooperation), Sukarno may meet the qualifications of a populist leader (Wertheim 1971, cited in Wieringa 2002). Willem Frederik Wertheim (1971) argues that Sukarno may be regarded as a populist based on two distinct qualities that he possessed: charismatic leadership and constant struggle against external threats. Sukarno was able to maintain an anti-foreign (anti-imperialism) narrative throughout his political career. Looking at Sukarno’s qualities, therefore, it would be problematic to label both Prabowo and Jokowi as populist leaders.

Edward Aspinall (2015) mentions that Prabowo qualifies as a populist leader for a couple of reasons: first, he invoked nationalism, describing Indonesia’s poor economic conditions as a product of the country’s exploitation by foreign powers; and second, he condemned the corruption of political elites and the environment of deceit and money politics fostered by many politicians, presenting himself as an anti-political outsider who could provide the strong leadership Indonesia needed.

Luky Djani and Olle Tornquist view Jokowi, the mayor of Solo city, and his deputy Rudy as populist leaders. They claim that both projected themselves as non-elitist mouthpieces for ordinary people’s ideas and ambitions, capable of establishing direct links with popular and civic partners in society (Djani and Tornquist 2017). It seems that these authors label Jokowi as populist due to his ability to make connections with popular and civil organizations outside the political parties and their bosses. They claim that Jokowi was a populist leader because of his role as a mouthpiece of the people and his connection to civic organizations. However, this qualification may differ from other understandings of populism, for example as defined by Mudde (2017).

Aspinall (2015), Mietzner (2015), and Djani and Tornquist (2017) claim that populism as a concept may be used to evaluate electoral politics. Perhaps the problem lies in the use of the word “populism,” as the word does not have an exact equivalent in Bahasa Indonesia. To underline their point that populism exists in Indonesia, the scholars look at politicians who qualify to fit into the category of populist leaders. Their claim seems to be based on limited characteristics of populist leaders: those who are anti-elite and anti-foreign. Their belief that populism exists in Indonesia is valid, but it does not meet the criteria of populism discussed above. There are three important elements of populism that are missing from these scholars’ discussions of populism in Indonesia: anger, anti-immigrant sentiment, and—most important—the division of society into groups of elites and the people, for example the Red and Yellow Shirts in Thailand. Even if an anti-immigrant political stance is replaced by anti-foreign sentiment, the other two elements are still missing.

Limits of Populism

Populism is not necessarily a suitable academic tool to understand the political and economic dynamics in Indonesia. This writing looks at the politics of economic growth. Efforts to improve the welfare of the population may be said to be the politics of growth. Indeed, poverty reduction is one of the massive political and economic attempts carried out by the Indonesian government. Indonesia successfully reduced its incidence of poverty from around 40 percent at the beginning of the New Order administration to less than 11 percent in 2017 (BPS, various years).

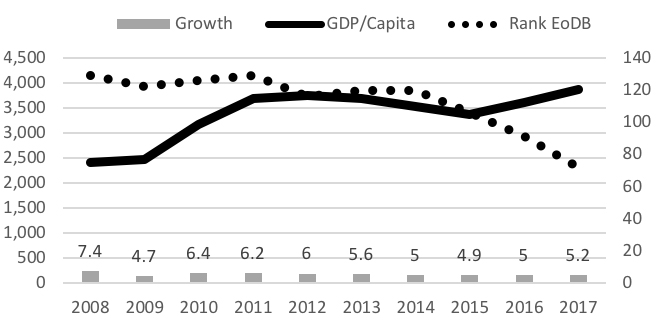

Right: Rank in ease of doing business; and annual growth in %

Sources: IMF, World Bank, and BPS

All governments in Indonesia (from Suharto to Jokowi) have pursued a politics of growth, aimed at high economic growth and increased income—in other words, improved welfare of the people. This aim is shared by neighboring countries. Indonesia is fortunate to have various natural resources that have supported its economic development over a relatively long period of time. The government has been able to shift from one resource to another depending on fluctuations in international markets. In the past the government relied on oil exports—crude palm oil—but now it depends on mining exports. Overall, Indonesia depends on primary products to boost its economic growth. In short, the government has the ability to maintain a politics of growth to improve welfare. It is also safe to claim that any government in Indonesia is driven by politics of growth to gain political legitimacy from voters.

The result of politics of growth can be seen in graph 1, where annual income per capita in the last ten years has increased significantly. It seems likely that the next or future governments would put their best efforts into increasing annual per capita income in order to improve welfare.

One of the main arguments for populism is anti-foreigner sentiment. On the other hand, the Indonesian government has been making efforts to create an investment-friendly environment. These two situations are contradictory, which makes it difficult for populism to find a strong foothold in the country. Over the last ten years, Indonesia’s rank in ease of doing business among the 190 nations in the World Bank study has been improving (graph 1). The Indonesian government’s effort to attract foreign investment is understandable, as the government is aware of its limited capability to collect domestic capital to continuously support economic growth. Creating a friendly investment climate is one way to maintain economic growth and open more jobs. Foreign direct investment (FDI) created almost one million jobs in Indonesia in 2016. 1 More important, the mining sector, a target of anti-foreign sentiment, is deeply connected to international production networks. It will put Indonesia in an awkward position if it has to cut this connection. Looking at the Indonesian government’s openness to investment, it is difficult to say that it harbors any anti-foreigner sentiment.

In short, politics of growth to improve welfare may not provide a political path for populism to emerge in Indonesia. With annual per capita income increasing in the last ten years, it would be difficult to find any resentment. All the governments have tried their best to address poverty by implementing various schemes to maintain hope among the poor. At least the government maintains the purchasing power of the poor so they can meet their basic needs.

Identity Politics

This paper argues that identity politics, rather than populism, is a salient explanation for understanding electoral politics in Indonesia. To understand the relevance of identity politics in explaining electoral democracy, this study offers one example: the Jakarta gubernatorial election of 2016–17. This was a three-way competition: Agus Yudhoyono-Sylviana Murni, Basuki Tjahaya Purnama-Djarot Wahyudi, and Anies Baswedan-Sandiaga Uno. Basuki is a Chinese-Indonesian politician, while Anies is Hadrami-Indonesian. Basuki is a Christian, and Anies is a Muslim. Basuki is a “double minority,” being Chinese-Indonesian as well as Christian. Based on the regulations, since there were no candidates that gained 51 percent of votes, the election needed to be continued with the two top gainers. Basuki and Anies contested in the second round, as Agus placed at the bottom.

Based on data collected from the National Election Committee (KPU) and National Statistics Agency (BPS) at the urban-village (kelurahan) level, Anies won the election. Anies won in about 80 percent of the total kelurahans in Jakarta. Basuki won in only 20 percent of them. The voters residing in kelurahans who voted for Anies and Basuki have very different characteristics in term of religion. This study uses the median, 87 percent, to characterize kelurahans with a Muslim population.

Anies garnered votes in kelurahans with more than 87 percent Muslim population. In contrast, Basuki won in kelurahans with a Muslim population of less than 87 percent. There was not a single kelurahan with a greater than 87 percent Muslim population that cast votes for Basuki. There is a very strong tendency for kelurahans with a large Muslim population to vote for Anies, and for those with a smaller Muslim population to vote for Basuki.

Mobilization of Identity

Anies overtly courted Muslim voters to deter them from choosing Basuki. On January 1, 2017 Anies met Rizieq Shihab (RS), who chaired the notorious Defender of Islam Front (FPI) in Petamburan. This particular meeting is of interest because Anies tried to widen Basuki’s social distance from voters. The FPI leader was a planner of several anti-Basuki demonstrations. Anies went to mosques and preached, and he also showed his closeness to radical or conservative Muslim groups. Anies gambled his political future by showing he was close to Muslims and that he represented Muslims.

Basuki in a visit to Thousand Islands regency on September 27, 2016 mentioned the Surat Al-Maidah (Quran verse 51) because the verse was often used by his political opponents to encourage voters to not vote for him. The verse states that no one should manipulate verses from the Quran for political purposes. It also states that Muslims and non-Muslims should not be allies. Basuki’s speech angered some clerics and Muslim leaders, who accused him of insulting Islam and its holy book by quoting a verse from it.

The Entrepreneurs of Identity

Action to Defend Islam (ABI, Aksi Bela Islam) provided an atmosphere in which Muslims could be easily manipulated. There were several Muslim rallies under the banner of ABI that aimed at toppling Basuki from governorship. These rallies intimidated Basuki supporters by placing banners in the mosques stating that they (Muslims) would not perform funeral prayers for Basuki supporters. In a situation of political contestation, the main duty of these entrepreneurs of identity was to create a constituency based on Islamic symbols. The term “entrepreneur of identity” was coined by Yves Besson (1990). This essay refers to Stephen Reicher and Nick Hopkins (2001), who argue that the politicians and social activists who define social identity and shape mass mobilization are entrepreneurs of identity. It appears that the mobilization of symbols was aimed at identifying “more pious” and “less pious” Muslims within the community.

In short, the entrepreneurs of identity found a powerful political weapon to use against Basuki. For these entrepreneurs, Basuki had committed blasphemy. RS, the leader of FPI, initiated a rally against Basuki on October 23, 2017. He was one of what this study refers to as entrepreneurs of identity. The rally poster claimed that the rally was to support the Indonesian Council of Ulama fatwa on Basuki and the Al-Maidah 51 case.

By evaluating the demonstrations organized by ABI, it should be clear that these events were constructed to strengthen an identity that was different from Basuki. The process of distinguishing between “we” and “they” took place between the ABI’s first and seventh demonstrations. The demarcation line that entrepreneurs of identity established was a choice between a Muslim leader and a non-Muslim one: Anies and Basuki. If a Muslim preferred to vote for Anies, she/he was a true Muslim. If she/he chose otherwise, her/his Islamic credentials were in doubt.

Middle-class Muslims in Jakarta seemed to be divided into two opposing camps: one supported Anies, while the other—much smaller—group supported Basuki. There is no clear indication that poor people voted for either Anies or Basuki. However, there are indications that Muslim middle-class votes were divided between Basuki and Anies. The Muslim middle class seemed to be divided in their religious outlook. Those who voted for Basuki were more relaxed in their understanding of Islam and had the ability to differentiate between religious doctrines and politics. They may have been observant of Islamic doctrines, but they rejected the use of those doctrines for political purposes. On the contrary, middle-class Muslims who voted for Anies claimed to be more pious. They seemed to be strict in their understanding of religious doctrines. Therefore, this group had a tendency to mix religious doctrines with politics. They were ready to use religion (in this case Islam) for political purposes.

Remarks

This study finds that identity politics seems to be a better concept than populism to explain voters’ behavior in the Jakarta election. Prasetyawan (2014) noted that in the 2007 and 2012 Jakarta gubernatorial elections, identity politics were at play to different extents. His study indicated that the use of identity politics in electoral contests tended to decrease. This essay offers an opposing finding, which is that the use of identity politics—in this case religion and ethnicity—increased.

Populism has many meanings, and they share similar characteristics. However, some studies on populism seem to ignore three important elements of populism scholarship: anger, anti-immigrant sentiment, and deep divisions within society that tear apart the existing social fabric. The Jakarta election may not fit into the category of populism, especially the one proposed by Mudde. Anies did not use anti-foreign or anti-elite messages in his campaign. He never suggested that voters who did not vote for him were not real Muslims. The entrepreneurs of identity who backed Anies never expressed any anti-foreign sentiment, even though they tried to foment mass anger against Basuki, and perhaps to some extent against Chinese-Indonesians. Their main message was anti-Basuki: they tried to put pressure on other Muslims to not vote for Basuki, and they labeled those who voted for him as supporting the blasphemer.

With the increasing trend of identity politics, in the 2017 Jakarta election there was an open possibility of seeing a “clash within” in Indonesia. Indeed, in Jakarta identity politics was at play from its first direct election in 2007, but the degree to which identity politics was used seemed to be acceptable as many candidates campaigned to prioritize native sons (putra daerah or asli) over migrants (pendatang). The play of identity politics in the 2017 election was much more brutal, combining religion and ethnicity. The extreme form of identity politics by combining religion and ethnicity had never been used in previous elections in Jakarta, even though it had been used in Medan, North Sumatra. There is a possibility that Anies’s identity politics will backfire against him—as Hadrami and not asli. If the growing trend of identity politics is not managed properly, Indonesia may imitate the “clash within” depicted by Martha Nussbaum (2007, 332) in India. Nussbaum identifies two opposing groups: one sees the unity of the nation as entailing political principles affirmed by people of different religions and ethnicities; the other sees unity as consisting of the majority’s exclusive commitment to a single religious/ethnic culture.

Wahyu Prasetyawan

Wahyu Prasetyawan, teaches Indonesian political economy at Syarif Hidayatullah Islamic University in Jakarta, Indonesia.

He received PhD from Kyoto University and MA from Leeds University, UK. He writes on Indonesian political economy, voting behavior, and natural resources conflict management.

Reference:

Aspinall, Edward (2015), “Oligarchic Populism: Prabowo Subiantos’ Challenge to Indonesian Democracy”, Indonesia, 99, pp.1-28

Besson, Yves (1990), Identites et conflicts au proche orient. Paris: L’Harmattan

Djani, Luky and Olle Törnquist (2017),” Dilemmas of Populist Transactionalism: What are the prospects now for popular politics in Indonesia?”, Polgov Publishing, Yogyakarta

Mudde, Cas (2004), “The Populist Zeitgeist,” Government and Opposition

Levitsky, Steven and James Loxton (2013), “Populism and Competitive Authoritarianism in the Andes,” Democratization, 20, 1, pp. 107-136

Mietzner, Marcus (2015), “Reinventing Asian Populism: Jokowi’s Rise, Democracy, and Political Contestation in Indonesia,” Poplicy Studies No 72, East West Center, Honolulu

Müller, Jan-Werner (2016),” What is Populism?” University of Pennsylvania Press

Prasetyawan, Wahyu (2014), “Ethnicity and Voting Patterns in the 2007 and 2012 Gubernatorial Elections in Jakarta, Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 33, 1, pp.29-54

Rathbun, Brian, Evgeniia Iakhnis and Kathleen E. Powers (2017), “This new poll shows that populism doesn’t stem from people’s economic distress,” downloaded from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/10/19/this-new-poll-shows-that-populism-doesnt-stem-from-economic-distress/

Reicher, Stephen and Nick Hopkins (2001), Psychology and the end of history: A critique and a proposal for the psychology of social categorization, Political Psychology, 22, 1

Wieringa, Saskia (2002), “Sexual Politics in Indonesia, ISS

Weyland, Kurt (2001), “Clarifying a Contested Concept: Populism in the Study of Latin American Politics”, Comparative Politics, 34,1

Notes:

- Indonesian Millennials Lean toward Xenophobia, Asia Times, November 18, 2017. http://www.atimes.com/article/indonesian-millennials-lean-towards-xenophobia/v, accessed November 19, 2017. ↩