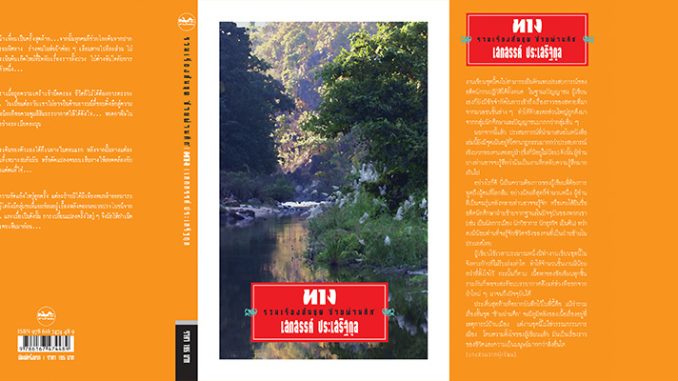

Book title: ทาง: รวมเรื่องสั้นชุดซ ายผ านศึก (The Path: stories of the veteran leftists)

Author: เสกสรรค์ ประเสริฐกุล (Seksan Prasetkul)

Publisher: Samanchon Books, 2016

Stories of the Lost Generation

Seksan Prasertkul is a well-known figure in Thailand for his outstanding and extraordinary profile. He was a leader of the student uprising against dictatorship in 1973, an ex-cadre of the now defunct Liberation Army of Thailand, a professor of a prominent university, and above all, a writer who is officially honored with the title ‘National Artist in Literature’.

The Path describes untold miseries experienced by some Thai leftists at the crucial moments of returning home having decided to withdraw from the jungle war. Their lives suddenly became empty as they had to struggle with both their past and present in order to mentally survive. Seksan notes that “though the stories’ background was politics but they were not political stories. They were essentially stories of human lives” (page 198). This book, therefore, has as its contents the combination of both modern Thai political history, especially from leftist intellectuals’ point of view, and the stories of individuals.

Human Path

The Path features six short stories: “Dream View,” “Noon Break,” “Moment of Truth,” “Rainy Night,” “A New Wound,” and “The Path.” Each story portrays the lives of an individual with a different personal background. However, they all share the same fate of political disillusionment which caused further misfortunes and almost unbearable pain. In this collection, readers will find stories of one protagonist whose heart was broken by complete ideological collapse, a young man who found out that life in the city was in fact another kind of battle ground, a warrior who lost his family he intended to rejoin, a middle-aged journalist whose painful experiences led him to a more painful attraction, a writer whose friendship with his old friend was threatened by their different ways of life, and an old man who tried to mediate the conflict between his former comrades amidst the latest political storm.

Looking closely at their lives, it is clear that the leftists’ “rebellious nature” played a big part in their destiny. It drove them toward armed struggles against the state in the jungle, which eventually led them to engage in fierce disagreement with their Communist leaders. And, of course, it also made it difficult for many of them to reintegrate mainstream values into their post-revolutionary lives. Even in old age, one protagonist carried out his ‘last rebellion’ by denouncing both his past and present, and turned towards spiritual pursuit instead.

Certainly, such ‘rebellious nature’ is a condition of their misery. In “Rainy night”, the protagonist even asks himself: “Does settled life have to include unacceptable surrender?” (page 95). He reflects his post-jungle urban life as a remaining leftist under the capitalist domination that he finds it always adds difficulties and complication as one could “break one’s heart endlessly with issues most people ignore” (page 95).

Meanwhile, a typical success in capitalist society could even bring dispute among close friends. In “A New Wound” the journalist said to his friend that “a wrong path will never lead us to the right goal, because its’ conditions will force us to change into something else which is not our true self” (page 140). But after his friend’s death, his position on the matter is somewhat compromised by harsh reality. He wished his friend were still alive, no matter what he would have become (page 147).

Being a leftist, however, is not the cause of all problems. Many sufferings transcended political inclinations, and were caused by human weaknesses. For example, the problem of personality cult and extremism could develop both among the leftists and the rightists. In “Noon Break”, the protagonist writes that “Chairman Mao already explained this, the party already instructed this….A revolutionary soldier has no right to commit suicide. His life belongs to the people. He is a property of the revolutionary movement, a valuable asset of the party, the organization” (page 48-49).

Obviously, being a leftist invites conflict with followers of the opposite ideology, but being human could also lead to conflict with any human being, or even with one’s self.

It is also true that their humanity made things more complex, especially when they had to pay the price for helping the underdog. Their emotional conditions also count. In “Dream view”, the protagonist said to himself while reflecting on his revolutionary past that “…If I no longer see any beauty in it, I have no reason to devote myself” (page 36). This might be a clue to their deep sorrow, because even when their dream is reduced from changing a nation to “having someone to understand…someone to help him stand and be his support in this kind of landscape” as the protagonist of “Noon break” reflects (page 47), such a small dream is still far from reality. The most extreme case for a jungle returnee in this collection is losing his beloved wife and child to a business man, his political enemy, as experienced by the protagonist of “Moment of truth” (page 78).

Though The Path is focused on the human aspect of the left, the fact that it is about political actors at crucial turning points in Thai political history, not to mention its author’s involvement in those events, makes this book inevitably political, or at least conveys certain political messages.

Political Path

The political side of The Path is presented at two levels. The first level appears directly through settings and dialogues.

All the protagonists are leftist activists from the period between students uprising (on October 14, 1973) and the bloody massacre at Thammasat university (on October 6, 1976). The young man in “Dream View” and a leading character in “Moment of Truth” joined the Communist-led armed struggles after 1976. Their occupations, as well as their attitudes towards the Communist party and politics suggest that the main protagonists in three stories (“Noon Break,” “New Wound,” and “The Path”) could be the 1973 leftists.

In terms of time span, this collection of short stories covers the period between 1981 and 2016. In other words, the book draws its contents from four decades of Thai politics, by taking up major conflicts and turning points of each decade as its settings. The themes presented in this collection range from the sudden collapse of the armed-revolutionary movements and the return of ex-jungle soldiers in 1980s (as in “Dream View,” “Noon Break,” “Moment of Truth”), to the rise of middle-class politics in capitalist democracy in 1990s, the same period when “China adopted the capitalist path, the USSR collapsed…and communist ideology exists only in text books” as in “A New Wound” (page 130). Readers can notice that the book also covers a decade of acute political confrontation in Thailand. As pointed out by some scholars, and starting in 2006, it was a decade in which liberalism and democracy are separated.

Hidden Path

The second level of political dimension of the book is the author’s “hidden transcript”. Seksan’s literary style puts meaningful points between the lines, where some are presented in the form of symbols. Surely, the book is enjoyable without the need to find those hidden messages. But, being aware of the symbols he uses and their related contexts would help expand the reader’s insights and feeling.

“Dream View” illuminates this important point. It is a story of a confused young leftist who was fascinated by a girl’s shadow on a glass wall of his neighbor’s bathroom. This fascination, however, broke his heart at the end. Seksan creates the naked girl’s shadow as an ideal, pure and beautiful. But eventually he brings a naked man’s shadow together with the girl’s into the same glass wall, and their love-making destroys the leftist’s beautiful dream, while suggesting the reality of life itself. This seemingly erotic scene is actually a display of symbolism, reflecting the Thai political situation in the 1970s, when many brave young students dreamed of a better society, both perfect and beautiful. But then, all of sudden their ideals were shattered by the harsh reality. Both the 1976 massacre and the collapse of the armed struggles in the early 1980s are well represented by the intrusion of a man’s shadow on the glass wall.

In contrast to “Dream View,” “Rainy Night” employs a different literary style in a simple form. In this story, Seksan successfully brings his readers into a rain forest to witness an ill-fated love affair between a lonely former leftist and a young woman. It is a story of a married- middle age journalist who is hiding in a mountain resort, as a result of his open criticism of the military government. There, despite his marital status, he fell in love with a smart-charming girl, but surely their relationship would not last long.

Looking beyond the middle-aged crisis plot and heart-breaking scenes, the backdrop of the story took is 1991 when the Thai Army, under the name of National Peace Keeping Council (NPKC), staged a coup d’état to overthrow Chatchai’s elected government and invited Mr. Anand Panyarachun, a popular figure among the Thai middle class, to be Prime Minister. One year later the NPKC held an election to show its nominal intention to return to democracy. But, it was obvious that the reinstalled parliamentary system was designed to keep the top-ranking officers in power. In May 1992 the situation led to a bloody confrontation between the middle class demonstrators and the army, pushing the latter out of political arena for more than a decade. Five years later, Thailand had a new constitution, which was drafted with popular participation, the so called ‘people’s constitution’.

It is interesting to note that despite the overthrow of an elected government, the 1991 coup, and the army-installed government led by Mr. Anand, was favored by the middle class. Yet within a year it was the same middle class that revolted against the newly elected government, with the coup leader becoming Prime Minister. The strange relationship between the middle class and the army, in a mutual erratic love affair with democracy, was already noticeable during this period. It was true in the 1990s and might be true in the decades to come.

In brief, the stories compiled in this book portray lives of ‘the Left’ and what’s left in their lives. Seksan’s profound writing brings us not only some truth about human lives, dreams and realities but also a political history of Thailand.

Reviewed by เอกสิทธิ์ หนุนภักดี (Ekasit Nunbhakdi)

(Ph.D. from Faculty of Political Science, Thammasat University)