With the rise of the Internet and the power of social media and blogging, traditional media is struggling to cope with the digitalization of news in the Philippines. The latter’s authority as a source of news and information is being countered by the former. In less than a decade, the Internet has changed the way Filipinos consume news. With all the challenges that the Philippine media is facing, this piece aims to answer the question: how did social media practitioners and bloggers shape the current Philippine media landscape?

Today the media landscape has reached a point where social media practitioners are being accredited to cover official government events in the Philippines. This was plainly evident during the initial ministerial meetings in August 2017 in preparation for the ASEAN Summit later that year (Macas, 2017). Yet citizen journalism is not new in the Philippines. Previously in 2009, bloggers under the civic group Blog Watch started writing about the preparations for the Philippine national elections that were to take place the following year. For their coverage they were able to interview most major political players. Later, in 2010, the Philippine Commission on Elections accredited the same bloggers to cover election activities and were later to be accredited by the Benigno S. Aquino III administration to cover several government functions (Lardizabal-Dado, 2017).

While earlier bloggers with a journalistic background collectivized and established a civic group ensuring transparency, today’s social media practitioners cannot be held to the same standards of professionalism.

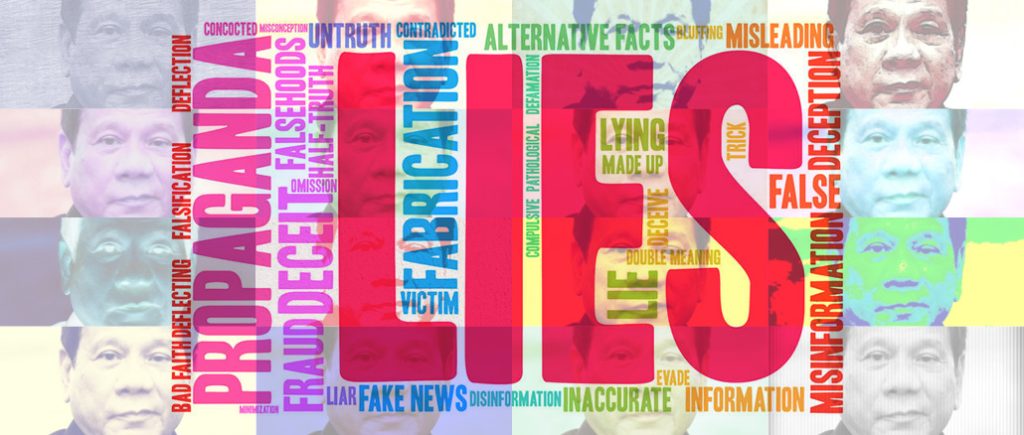

Pro-Duterte social media practitioners Margaux ‘Mocha’ Uson, lawyer Bruce Rivera, and bloggers such as RJ Nieto and Sass Sasot have a significant social media followings in the Philippines – big enough for Uson to be appointed by current Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte as assistant secretary for social media in the presidential communications office (Sabillo & Gonzales, 2017) and for Nieto to be hired as a consultant at the Department of Foreign Affairs (Politiko, 2017). They, along with the ones currently holding positions in the government, continue to express political opinion and support Duterte. The Ka-DDS (Duterte Diehard Supporters), as they call themselves, are allegedly spreading false information and ‘fake news’ in an effort to defend the president’s actions on the drug war and other human rights concerns (Ballaran, 2017).

History of Blogging in the Philippines

Blogging started in the Philippines in 1995, a few years after the country got access to the World Wide Web. Most of the emerging blogs focused on lifestyle, culture, and science and technology. In 2005, an attempt to connect the socio-political aspect of blogging to the users of the Internet was introduced during the first Philippine Blogging Summit (Yugatech, n.d.). To further strengthen the civic involvement of bloggers in the country, the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism trained nine bloggers in 2009 with a seminar on “Covering Elections in the Era of Internet and Automation.” It was from these nine bloggers that the civic group Blog Watch was formed. Blog Watch was the first independent online group of bloggers that were accredited by the Philippine Commission on Elections and the Philippine Government to cover election-related activities and government functions starting in 2010. Members of the group had a journalistic background and were familiar with the standards for authenticating and verifying data (Lardizabal-Dado, 2017). Moving to today, the blogging scene in the Philippines is diverse and comprehensive enough that it spans from culture, fashion, lifestyle, politics, gadgetry, science and technology, history, and even specific niches in genealogy and popular culture, and so forth.

Duterte’s Social Media Influence versus Traditional Media

According to GSMA Intelligence, 47% of the Philippine population has access to mobile data and an Internet connection (Garcia, 2016). With this figure, the popularity of social media practitioners increased and by 2015, the year before the Philippine national elections, ‘digital journalists’ had gained a significant following and influence over the Filipino Internet users. The dominant and most outspoken social media practitioners are the DDS (Duterte Diehard Supporters), a group of popular artists, lawyers, bloggers, and other public figures that supported the campaign of the then Davao City mayor and presidential aspirant, Rodrigo Duterte. The acronym DDS was initially known as the Davao Death Squad, a vigilante group allegedly headed by Duterte himself that was involved in the killings of top criminals in the said city. Duterte was to become President in 2016.

The DDS later shifted from being part of Duterte’s campaign machinery to being a general support group for the newly-elected president. Top social media practitioners Margaux ‘Mocha’ Uson and RJ Nieto, each respectively with more than a million followers on Facebook, were appointed to top government positions. Uson became the assistant secretary for social media under the presidential communications office, and Nieto was hired as a consultant on migration issues at the Department of Foreign Affairs. Everyone, including the two new government officials, continued to express political opinions in support of Duterte. Moreover, they have been accused by the opposition in spreading ‘fake news,’ particularly in corruption allegations against Senator Antonio Trillanes IV (Ballaran, 2017), using photos glorifying the actions of the President to mislead the public (De Jesus, 2017; Ranada, 2017), and many other cases of malfeasance, most of which are fact-checked and denounced by the traditional media.

Duterte’s rhetoric on alleging the media to be ‘biased’ and ‘paid for by the oligarchs to destabilize his government’ is being utilized by his popular supporters in social media in an attempt to discredit and remove the established authority of the traditional media (Corrales, 2016; Morallo, 2017; Morales & Cruz, 2017). Another challenge that traditional media is facing is the trooping of trolls – those that post a deliberately provocative message on social media or a message board with the intention of causing maximum disruption and argument – paid by the PDP-Laban, Duterte’s own political party (Bradshaw & Howard, 2017). Moreover, other actions from the presidential communication’s office being seen to undermine professional journalism is the accreditation of social media practitioners with at least 5,000 followers on Facebook, Twitter, and other social media sites, so they might cover official government activities (Macas, 2017).

Yet despite all these threats, the traditional media remains resolute in doing its job, acting as the fourth estate in ensuring accountability and transparency in the government (Gavilan, 2016).

Falling Short in the Common Elements of Professional Journalism

In less than a decade, bloggers and social media practitioners became major players in the Philippine media industry. Bloggers with a journalistic background collectivized themselves and established a civic group ensuring transparency and accountability within the government. Guided with the highest standards of journalism, they were able to receive accreditation from the government to cover official events. Today, social media practitioners have power because of their links with Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte. They rail with his populist rhetoric against the traditional media, thereby undermining its authority as the fourth estate. Lastly, the presidential communications office increased their fleet by accrediting more social media practitioners, those with more than 5,000 followers on social media sites. Challenges aside, the traditional media continues in its effort to present the facts to its readers.

The status of social media practitioners as members of the press corps, their actions and practices, and their ‘standards’ of journalism, are all still hot topics of discussion. Yet it is plain that accredited social media journalists in the Philippines are falling far short in the common elements of professional journalism; that is, principles of truthfulness, accuracy, objectivity and impartiality.

Jeconiah Louis Dreisbach

Jeconiah Louis Dreisbach is a Master of Arts candidate in Philippine Studies at De La Salle University, Manila. (jeconiah_dreisbach@dlsu.edu.ph)

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, Issue 23, YAV, August 2018

References

Ballaran, J. (2017, September 22). Trillanes files raps vs Mocha Uson over ‘fake news’. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved from http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/932625/trillanes-files-raps-vs-mocha-uson-at-ombudsman-over-fake-news

Bradshaw, S., & Howard, P. N. (2017). Troops, Trolls and Troublemakers: A Global Inventory of Organized Social Media Manipulation [Scholarly project]. In Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford. Retrieved from http://comprop.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/89/2017/07/Troops-Trolls-and-Troublemakers.pdf

Corrales, N. (2016, May 10). Duterte hits media for sensationalism, bias. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved from http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/784772/duterte-hits-media-for-sensationalism-bias

De Jesus, S. (2017, October 23). Mocha Uson on defensive over misleading Marawi photo from PCOO-managed page. Rappler. Retrieved from https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/186105-pcoo-mocha-uson-misleading-marawi-photo

Garcia, K. (2016, January 29). Statistics on broadband and mobile Internet in the PH. Rappler. Retrieved from https://www.rappler.com/brandrap/tech-and-innovation/120737-ph-internet-statistics

Gavilan, J. (2016, August 14). Why bother to fact-check the Duterte list? Rappler. Retrieved from https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/rich-media/143017-fact-checking-rodrigo-duterte-drug-list-newsbreak

Lardizabal-Dado, N. (2017, October 09). History of Blog Watch. Retrieved from http://blogwatch.tv/about/history-of-blog-watch/

Macas, T. (2017, August 9). Adult social media users with 5k followers can cover Duterte events –PCOO. GMA News Online. Retrieved from http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/news/nation/621238/adult-social-media-users-with-5k-followers-can-cover-duterte-events-pcoo/story/

Morales, N. J., & Cruz;, E. D. (2017, March 31). Philippine media groups cry foul over Duterte’s diatribes. Retrieved November 03, 2017, from http://www.reuters.com/article/us-philippines-duterte-media/philippine-media-groups-cry-foul-over-dutertes-diatribes-idUSKBN172130

Morallo, A. (2017, March 30). Duterte blasts media organizations for ‘unfair, twisted’ coverage. Philippine Star. Retrieved from http://www.philstar.com/headlines/2017/03/30/1686079/duterte-blasts-media-organizations-unfair-twisted-coverage

Politko. (2017, July 07). Thinking Pinoy designated new DFA consultant. Retrieved from http://politics.com.ph/thinking-pinoy-designated-new-dfa-consultant/

Ranada, P. (2017, May 30). PNA sorry for wrong photo; Mocha Uson on the defensive. Rappler. Retrieved from https://www.rappler.com/nation/171415-philippines-news-agency-wrong-photo-mocha-uson

Sabillo, K., & Gonzales, Y. (2017, May 09). Mocha Uson appointed as PCOO assistant secretary. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved from http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/895511/mocha-uson-appointed-as-pcoo-assistant-secretary

Yugatech. (n.d.). Tracing Back the Philippines’ Blogging History. Retrieved from http://www.yugatech.com/tracing-back-the-philippines-blogging-history/