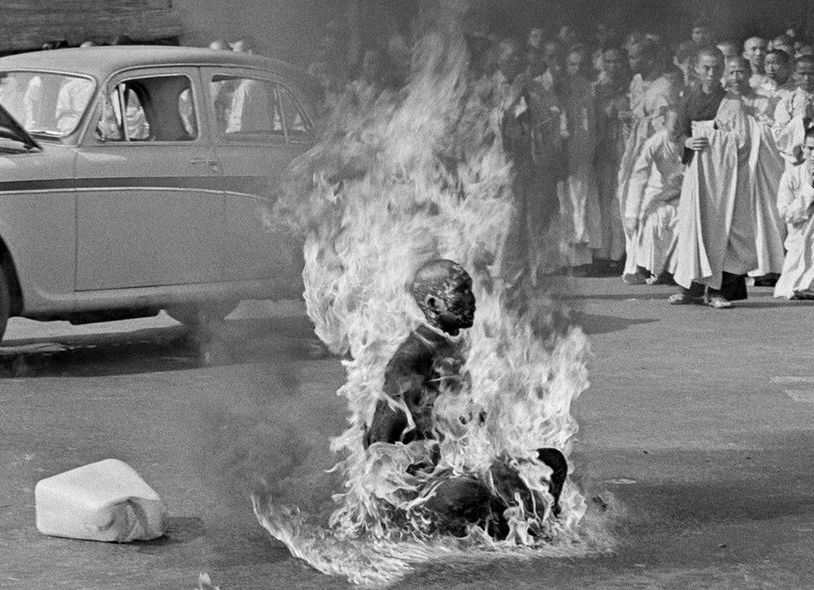

On June 11, 1963, an elderly Vietnamese Buddhist monk named Thích Quảng Đức burned himself to death at a busy intersection in Saigon. His act left an indelible image on the Viet Nam War. This was partly due to the iconic photographs taken by the Associated Press reporter Malcolm Browne. These photographs, though documenting a death so intimately, did no more to it than merely tracing its fiery outline on the body of the Buddhist monk. Even a day later, when the photographs circulated throughout the world, all that was known about the Buddhist monk remained insignificant and read like a police report. “A 73-year-old Buddhist priest,” David Halberstam writes, “committed suicide to dramatize the Buddhist’s protest against the Government’s policies on religion.” 1

Biography

The Vietnamese Unified Buddhist Church published a biography for Thích Quảng Đức soon after his death. The biography describes Thích Quảng Đức’s life as an ordinary life of a Buddhist monk. 2 At the age of seven, Thích Quảng Đức became a novice, and at the age of twenty, he ordained. 3 After ordination, Thích Quảng Đức then traveled throughout Vietnam, particularly southern Vietnam, to promulgate Buddhism. The biography, in fact, glosses over his life to focus on his death and its impact since it was his death that moved the world and, ultimately, brought his life into focus.

What the biography does not mention is that Thích Quảng Đức’s death was a planned event. It was not a spontaneous act of martyrdom that the photographs by Malcolm Browne seem to portray. In a sense, the unfolding of Thích Quảng Đức’s death reveals nothing about his life but rather the complex relationship between American reporters and Vietnamese Buddhist monks at the time. And to reduce this relationship to mere one-sided exploitation is to completely miss the circumstances that set the stage for Thích Quảng Đức’s self-immolation.

For months, American reporters, such as David Halberstam, Neil Sheehan, and Malcolm Browne, frequented Xá Lợi pagoda because there was a rumor that Vietnamese Buddhist monks would either disembowel or burn themselves publicly to protest religious oppression by the Diệm regime. The goal of the American reporters was to take pictures of these events since they would sell newspapers. Halberstam explains, “[It] was the nature of the game.” 4 Thus, when Ray Herndon, who was “pinch-hitting” for Sheehan in Vietnam, forgot his camera at home on June 11, 1963, he knew that he had just “lost the Pulitzer.” 5 He did indeed. Browne won the Pulitzer in 1964 for the photographs he took of Thích Quảng Đức’s self-immolation.

The Vietnamese Buddhist monks used the relationship to further their cause. The Buddhist monks would use the American reporters to lure the secret police away from the pagoda by giving them a false location far away from the site of demonstration. The Buddhist monks also used the reporters to voice their struggle. The night before the immolation, Thích Đức Nghiệp, who was the primary spokesman of the Unified Buddhist Church, called Malcolm Browne to inform him of Thích Quảng Đức’s self-immolation. In addition, Thích Đức Nghiệp and a few other monks orchestrated the whole plan. They arranged for the car, the driver, the gasoline, and the human chain that would stop the police from extinguishing the fire burning on Thích Quảng Đức’s body.

With the American reporters and Vietnamese Buddhist monks setting the stage, Thích Quảng Đức played his part perfectly. Yet no one wondered, “Was he a mere pawn in this game? What did he die for?” In one of the poems he left for his disciples, Thích Quảng Đức expressed that the intention of his self-immolation was to benefit Vietnamese Buddhists. He envisioned his body burning like “a lamp shining into darkness,” which would lead those that were lost to shore. 6 As his body burned, the smoke, like the fragrance of burning joss sticks, would bring calmness and inform those who were “ignorant” of the Diệm regime’s repression of Buddhism. 7 Once the body stopped burning, the ash, Thích Quảng Đức imagined, would “fill the gap of [religious] inequality” between Buddhism and Catholicism. 8 Thích Quảng Đức then hoped that his spirit would continue to help Buddhists by awakening others. 9

Sutra and Text

The American public was moved by Thích Quảng Đức’s self-immolation, but some could not accept the act. During a flight from New York to Stockholm, an American woman told Thích Nhất Hạnh that Thích Quảng Đức’s self-immolation “seemed to her the act of an abnormal person.” 10 In other words, she “saw self-burning as an act of savagery, violence, and fanaticism, requiring a condition of mental unbalance.” 11 Thích Nhất Hạnh, in return, tried to explain to the woman that during the year he lived with Thích Quảng Đức, he “found him a very kind and lucid person, and that he was calm and in full possession of his mental faculties when he burned himself.” 12 The woman did not believe him.

The act of self-immolation, in fact, has its religious roots in the ordination ceremony as practiced in the Mahayana tradition. During the ceremony, Thích Nhất Hạnh explained, “the monk-candidate is required to burn one, or more, small spots on his body in taking the vow to observe the 250 rules of a bhikshu, to live the life of a monk, to attain enlightenment and to devote his life to the salvation of all beings.” 13 And for reciting the vow in front of the sangha while experiencing this kind of pain, the monk candidate shows the “seriousness” of his “heart and mind.” 14The act of self-immolation can also be traced to the Lotus Sutra, which is “one of the most important and influential of all sutras or sacred scriptures of Mahayana Buddhism.” 15

In the chapter “Former Affairs of the Bodhisattva Medicine King,” the Buddha tells a story of the Bodhisattva Gladly Seen by All Living Beings immolating his body for the Buddha Sun Moon Pure Bright Virtue because he felt that all the offerings that he had made was “not as good as making an offering of … [his] own body.” 16

For those that practice self-immolation, the Lotus Sutra promises magical benefits. According to the chapter “Former Affairs of the Bodhisattva Medicine King,” the Lotus Sutra not only “can save all living beings” but also “can cause all living beings to free themselves from suffering and anguish.” 17 To describe its impact, the sutra compares it to “someone in darkness finding a lamp, a traveling merchant finding his way to sea…[and] a torch that banishes darkness.” 18

Similarly, Thích Quảng Đức hoped that his self-immolation would have the same impact as described in the Lotus Sutra. For instance, in one of the poems that he left behind, Thích Quảng Đức wrote that he wanted to use his burning body as “a lamp shining into darkness,” which would lead those that were lost to shore. 19 And as his body burned, the smoke, like the fragrance of burning joss sticks, would “awaken” those who were “ignorant” of the Diệm regime’s repression of Buddhism. 20 Once the body stopped burning, the ash, Thích Quảng Đức imagined, would “fill the gap of [religious] inequality.” 21 At the end of this process of burning the body, Thích Quảng Đức then hoped that his spirit would continue to help Buddhists awakening others. 22

Thích Quảng Đức did not intend his self-immolation to be a political act of resistance against the Diệm regime, as the American correspondents or Buddhist leaders declared, but rather a performance of the Lotus Sutra to help Vietnamese Buddhists. In other words, Thích Quảng Đức performed the Lotus Sutra by immolating himself, so that he could free Vietnamese Buddhists from their suffering.

Remembering in Supplements

In 1966, three years after Thích Quảng Đức’s self-immolation, the bookstore Chi Lăng in Saigon published a peculiar version of Thích Ca Lược Sử (The Life of the Buddha). Instead of featuring the Buddha prominently on its cover, the book has a picture of Thích Quảng Đức meditating in front of an image of the Buddha. The bright turmeric color of Thích Quảng Đức’s robe and that on the image of the Buddha implies a linkage between the two. Yet, the most interesting part about the book is that it includes a supplement on Thích Quảng Đức’s self-immolation, implying that the act is a part of the larger Buddhist history.

The year 1966 was pivotal to the Buddhist Struggle Movement. The movement contributed to overthrowing the Diệm regime in November 1963 and became a force to be reckoned with. As the Buddhist Struggle Movement grew in strength, the narrative on its aim began to shift further and further from its religious context. In a sense, the religious and political could not coexist. Ultimately, the generals of the Republic of Vietnam deemed the movement political and crushed it by force with Thích Trí Quang placed under house arrest and Thích Nhất Hạnh exiled. 23

In 2010, almost fifty years too late, the Vietnamese government opened its commemoration site for Thích Quảng Đức at the corner where he immolated himself. Again, Thích Quảng Đức’s self-immolation played the role of a historical supplement. But this time, its aim was to tie the Buddhist Struggle Movement to the Communist nationalist version of Vietnamese history.

Google Maps Street View of commemoration sites

At the center of the commemoration site was a bronze statue of Thích Quảng Đức engulfed in flame (top banner image). The face of the statue is calm while fire swirls around the body. And in the back of the statue stands a long mural depicting Army of the Republic of Vietnam soldiers beating Buddhists at one end and Buddhist monks standing and praying in solidarity with National Liberation Front soldiers at the other end.

The plaque at the front of the commemoration site recites the biography of Thích Quảng Đức. But it also clearly states that the city built the site to commemorate the sacrifice and contribution Thích Quảng Đức had toward the “dharma, peace, national independence and unification.”

But across the street, a smaller commemoration site for Thích Quảng Đức built in 1967 by the Unified Buddhist Church stood almost in defiance. The site did not have any plaques. The three important historical markers the site had were Thích Quảng Đức’s birth year, the year he ordained, and the year he immolated himself. The site states: “for Buddhism, he immolated himself.”

Hoang Ngo

Workforce Development Council of Seattle – King County

Reference

Dialogue (The Rev) Thich Nhat Hanh, Ho Huu Tuong, Tam Ich,Bui Giang, Pham Cong Thien Addressing to (The Rev) Martin Luther King, Jean Paul Sartre, André Malraux, René Char, Henry Miller. Saigon: La Boi, 1965.

Halberstam, David. “DIEM ASKS PEACE IN RELIGION CRISIS; But Buddhists Still Protest Dispute Seems Worse No Easing in Dispute Demonstration Defies Ban.” New York Times, June 12, 1963.

Lê Mạnh Thát, ed. Bồ Tát Quảng Đức: Ngọn Lửa và Trái Tim. [Ho Chi Minh City]: NXB. Tổng hợp Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh, 2005.

Nhất Hạnh. Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire. 1st ed. New York: Hill and Wang, 1967.

Prochnau, William W. Once Upon a Distant War. 1st ed. New York, N.Y: Times Books, 1995.

Quốc Tuệ, ed. Công Cuộc Tranh Đấu Của Phật Giáo Việt Nam: Từ Phật Đản Đến Cách Mạng 1963. [Saigon]: the Author, 1964.

Schecter, Jerrold L. The New Face of Buddha; Buddhism and Political Power in Southeast Asia. New York: Coward-McCann, 1967.

Thích Thiện Ngộ. Thích-Ca Lược Sử: Phụ-Thích A-Di-Đà – Tóm Lược Bảy Vị Bồ Tát Phụ-Bản Thích Quảng Đức. Saigon: Quán Sách Chi Lăng, 1966.

Watson, Burton, trans. The Lotus Sutra. Translations from the Asian Classics. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

Notes:

- David Halberstam, “DIEM ASKS PEACE IN RELIGION CRISIS; But Buddhists Still Protest Dispute Seems Worse No Easing in Dispute Demonstration Defies Ban,” New York Times, June 12, 1963, 3. ↩

- See Lê Mạnh Thát, ed., Bồ Tát Quảng Đức: Ngọn Lửa và Trái Tim ([Ho Chi Minh City]: NXB. Tổng hợp Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh, 2005). ↩

- The birthyear of Thích Quảng Đức is not clear. In some publications, like Thích Thiện Ngộ, Thích-Ca Lược Sử: Phụ-Thích A-Di-Đà – Tóm Lược Bảy Vị Bồ Tát Phụ-Bản Thích Quảng Đức (Saigon: Quán Sách Chi Lăng, 1966), 248., he was born in 1890. In some others, he was born in 1897. ↩

- William W Prochnau, Once Upon a Distant War, 1st ed (New York, N.Y: Times Books, 1995), 320. ↩

- Prochnau, 316. ↩

- Quốc Tuệ, ed., Công Cuộc Tranh Đấu Của Phật Giáo Việt Nam: Từ Phật Đản Đến Cách Mạng 1963 ([Saigon]: the Author, 1964), 113. ↩

- Quốc Tuệ, 113. ↩

- Quốc Tuệ, 113. ↩

- Quốc Tuệ, 113. ↩

- Nhất Hạnh, Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire, 1st ed. (New York: Hill and Wang, 1967), 1. ↩

- Nhất Hạnh, 1. ↩

- Nhất Hạnh, 1. ↩

- Dialogue (The Rev) Thich Nhat Hanh, Ho Huu Tuong, Tam Ich, Bui Giang, Pham Cong Thien Addressing to (The Rev) Martin Luther King, Jean Paul Sartre, André Malraux, René Char, Henry Miller (Saigon: La Boi, 1965), 14. ↩

- Dialogue, 14. ↩

- Burton Watson, trans., The Lotus Sutra, Translations from the Asian Classics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), ix. ↩

- Watson, 282. ↩

- Watson, 286. ↩

- Watson, 286. ↩

- Quốc Tuệ, Công Cuộc Tranh-Đá̂u Của Phật-Giáo Việt-Nam, 113. ↩

- Quốc Tuệ, 113. ↩

- Quốc Tuệ, 113. ↩

- Quốc Tuệ, 113. ↩

- See Jerrold L Schecter, The New Face of Buddha; Buddhism and Political Power in Southeast Asia (New York: Coward-McCann, 1967). ↩