A published translation from Japanese by the Editorial Office of Rekidai Hoan, Okinawa Archives, Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education, March 2003.)

Origin of the Diplomatic Documents of the Ryukyu Kingdom

A 444-Year Record (1414-1867)

The current Rekidai Hoan represents a fraction of the original archive compiled under the auspices of the Ryukyu Kingdom. While incomplete, the surviving documents nevertheless provide a partial record of diplomatic correspondence exchanged between 1424 and 1867, encompassing a period stretching from the third year of the reign of Ryukyu King Sho Hashi to the twentieth year of the reign of King Sho Tai, the last monarch to rule the Ryukyu Kingdom before its dissolution and incorporation into the Japanese state during the Meiji Restoration of January 1868. The collection thus spans the entire period from the twenty-second year of the reign of Ming Dynasty Emperor Eiraku (Yong Le) to the sixth year of Emperor Dochi (Tong Zhi) of the Qing Dynasty.

The original archive consisted of three separate collections of documents containing 262 volumes and a four-volume supplement, of which 20 volumes remain unrecorded. Nevertheless, the surviving transcripts remain an invaluable historical record. Among documents included in the archive are copies of decrees handed down by the emperors of Ming and Qing dynasties, trade permits issued by the Chinese central government, and official correspondence from the municipal government of Fujian. Copies of outgoing correspondence from the Ryukyu Kingdom have also been preserved, including official letters sent by Ryukyu kings to imperial China and official documents issued by the king to local subjects authorizing travel to China. In addition to these documents, a smaller supplement to the original collection provides a record of contact between the Ryukyu Kingdom and countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, and France. Documents relating to the kingdom’s “Golden Age” of trade with East Asian trading centers are contained in the first collection.

The Three Collections

Although the archives originally functioned as a resource for diplomats drafting new correspondence and studying the art of diplomacy – hence its title Rekidai Hoan (Precious Documents of Successive Generations) – today its primary importance lies in its role as a source of diplomatic materials relating to the Ryukyu Kingdom. For the purpose of retaining the integrity of the original archive, the reconstruction of material from the original record has honored the three original compilations.

The first of these, commissioned in 1697, contains documents relating to the longest period of the kingdom’s history. Initially documents were produced in duplicate, with copies held at the Ryukyu seat of government at Shuri Castle, and replicas stored in Kume Village. The original compiler, Saitaku, was appointed by Sho Tai to create the archive in 1697. At that point, a more than 300-year history of diplomatic correspondence with China already existed, dating back to at least 1372, the documentary record of which the Ryukyu Kingdom administration commissioned Saitaku to arrange according to region and style.

Unlike the first collection, the second and third were arranged chronologically. The first of these, commissioned by the Ryukyu administration to cover the intervening period from the first collection, was compiled under the auspices of Tei Junsoku in 1858. The third compilation, this time completed by civil servants, contained documents relating the final years of the kingdom from 1858 and 1867.

Documents Recovered from Kume-mura

When the Shuri administration commissioned the original compilation of the Rekidai Hoan, documents were retained in duplicate with records stored both at the Ryukyu seat of government at Shuri castle and in Kume-mura. This Chinese enclave was established as early as the late fourteenth century, when the Satto Dynasty first initiated a tributary relationship with the Chinese imperium. Its first inhabitants were experts in diplomatic, epistolary, and navigational fields invited from Fujian Province to support the Ryukyu Kingdom. Their subsequent role included acting as intermediaries between their Okinawan hosts and the Chinese suzerains, for which they considered a duplicate documentary record essential.

As with Chinese enclaves located in other Asian port cities, the development of trade between Naha and China allowed the Kume enclave to flourish and exercise considerable influence over the economic and political administration of the Ryukyu Kingdom. During the Ming Dynasty this led to the development of a distinctive Chinese settlement in which the resident experts, known as binjin 36 sei, largely adhered to Chinese customs and referred to themselves as Toei. However, after the succession of the Qing Dynasty, whose customs they refused to follow, the Chinese community gradually assimilated into Ryukyuan society.

The Rekidai Hoan was originally housed at the Tenpi Shrine in the village, but after the abolition of the Ryukyu Kingdom the documents were considered at risk and were therefore distributed among members of leading families within the community before eventually being secreted at the village school, Meirindo. After being brought to the school, the whereabouts of the collection remained concealed until 1933 when its revelation to the general public attracted enormous attention

A debate quickly ensued regarding the destination of the collection, with local historians successfully arguing in favor of allowing public access to the record. As a result, village elders agreed on November 14, 1933, to release the documents into the custodianship of the prefectural library under the condition that the original documents would be safeguarded and public access restricted to transcripts of the original documents.

Original Documents Scattered and Burnt

Shuri Originals Destroyed in Great Kanto Earthquake

The original Rekidai Hoan was stored at the Ryukyu Kingdom seat of government at Shuri Castle until 1867, but was then transferred by accession to the Ministry of Home Affairs in Tokyo on the dissolution of the Ryukyu Kingdom. Tragedy later struck when the entire record was consumed by fire during the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923.

Kume Collection Destroyed in Battle of Okinawa

Subsequently, the Kume documents, which were housed in the prefectural library, became the only surviving record. However, the elation surrounding its rediscovery in 1933 was relatively short-lived, as despite the efforts of library staff to transfer documents to the north of the island as conflict loomed, the Kume collection was itself destroyed in its entirety during the 1945 Battle of Okinawa, an event which symbolizes the tragedy and loss war has inflicted on the islands.

As a result, both the original archives of the Rekidai Hoan, which had provided a record of over 400 years of Ryukyu Kingdom history dating back to the fifteenth century, were lost to the world.

Remaining Blueprints and Transcripts

- Although the original documents were destroyed during the Kanto earthquake and the Battle of Okinawa, many copies were made as a result of the efforts of the following institutions and individuals and subsequently survived.

- A Yoshitaro Kamakura, a teacher at the former Prefectural First Women’s High School, cyanotyped a number of documents which are now housed at the Okinawa Prefectural Arts University Library and Arts Museum.

- Kanjun Higashionna transcribed and cyanotyped a number of documents now housed at the Okinawa Prefectural Library.

- Shigeru Yokoyama transcribed a number of documents, some of which are now housed at Hosei University, Institute of Okinawan Studies.

- Kokuei Kuwae was asked to transcribe a number of documents, which were retrieved by US forces after World War II. These were subsequently housed at the Ryu-Bei (Ryukyu-US) Cultural Center, and are now kept at Naha Municipal Library.

- Seisei Kuba was commissioned by the former Imperial University of Taipei to transcribe a large number of documents which form part of the collection maintained by National Taiwan University Library.

- The Historiographical Institute, University of Tokyo, instructed the Prefectural Library to transcribe materials which still remain at the institute.

An Alternative Version of the Rekidai Hoan

In the absence of original documents, the term “Rekidai Hoan” has been conferred upon the material remaining in the collections outlined above. The following offers a summary of the quality and number of documents contained in these collections.

The Kamakura cyanotypes, although incomplete, remain the best preserved and most complete copy of the Kume records. These cyanotypes contain copies of thirty-six volumes of the first collection, seventeen of the second, two volumes of the third, and the first volume of the additional series. In addition, the Historiographical Institute, the University of Tokyo created microfilm copies of these cyanotypes. Nevertheless, the first and the twelfth volumes of the first collection were lost when they were transferred to the Okinawa Prefectural University of Arts.

The Higashionna cyanotypes were originally of a superior resolution to those in the Kamakura collection, but the photographs were subsequently exposed to vermiculation. Although the collection contains fewer documents than the Kamakura collection, these include the twenty-fourth volume missing from the Kamakura documents. Higashionna’s transcripts consist of thirty volumes copied by hand, though in replicating the fourteenth volume, Higashionna reduced the total collection to twenty-nine. This collection is nevertheless highly valued as an authentic record of the original documents as Higashionna resisted the impulse to insert speculative material in place of effaced sections, instead using footnotes to indicate their possible content.

Yokoyama’s transcripts, like the other surviving documents were created while the duplicate collection remained intact in Kume village. Yokoyama transcribed approximately one hundred documents, and fearing for their preservation, handed some of these to Higashionna, who managed to preserve thirteen volumes intact and return them to Yokoyama. Others were destroyed during the war.

Transcripts produced under the auspices of the former prefectural library were created by several scholars, working under the supervision of sinologist Kokuei Kuwae. A total of thirty-one volumes were transcribed from the first compilation and sixty-five from the second. These hand copies were then collated with the originals for verification.

National Taiwan University collection provides the most complete record of correspondence and encompasses almost the entire original collection. However, the authenticity of the transcripts held in Taiwan has been compromised by the insertion of speculative material to compensate for omitted and effaced sections. In the postwar period, copies of these altered documents were made available on microfilm to the University of Hawaii and other institutions. Cyanotype versions were also produced.

Documents retained by the University of Tokyo include thirty-eight volumes of the first compilation transcribed by the prefectural library at the request of the Historiogaphical Institute, University of Tokyo.

The Tei Ryohitsu documents consist of samples transcribed from the first and second collections maintained in Kume during the nineteenth century.

The Rekidai Hoan as a Copy of Original Correspondence

Although the Rekidai Hoan provides a valuable historical record of diplomatic relations during the Ryukyu Kingdom period, it does not include earlier documents relating to initial contacts between the kingdom and imperial China. While Chinese sources indicate envoys were dispatched from the Ryukyu Kingdom at the invitation of the first Ming Emperor Taizu as early as 1372, during the twenty-third year of the reign of King Satto, the oldest documents within the record date back to the second year of the reign of King Sho Hashi in 1424. Although diplomatic documents pertaining to contacts during the intervening period were undoubtedly produced, none have survived.

As the word hoan (precious) indicates, the documents were considered of great importance, as they functioned as a guide for scribes drafting diplomatic correspondence. Documents which were considered inadequate for or superfluous to this purpose were therefore discarded. As a result much of the diplomatic record was discarded.

All diplomatic documents recorded in the Rekidai Hoan are duplicates of original documents made during the Ryukyu Kingdom era. Incoming correspondence from China and other countries was transcribed and preserved at the diplomatic office in Kume-mura. In addition, duplicates of outgoing correspondence drafted by Kume diplomats were also preserved. These were initially kept in Kume-mura, where they remained until the Ryukyu administration, fearing that they were likely to be lost, requested that they be collected into the Rekidai Hoan. As the record consisted of copies of originals housed in China, it is possible to detect differences by comparing remaining transcripts with original documents. For example, some Kume drafts do not include the names of envoys. Thus, although the Rekidai Hoan is highly valued as a diplomatic record, it is not complete. Therefore, to obtain a more accurate information on the diplomatic history of the kingdom, researchers need to compare and contrast material with other related historiographical sources to glean details and ascertain the accuracy of material in the surviving transcripts.

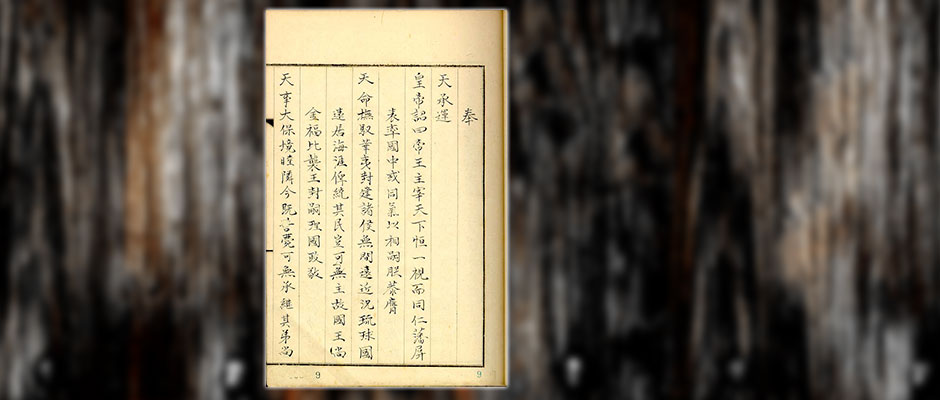

The Rekidai Hoan

The First Collection (1424-1697)

Copies of forty-two of the forty-nine transcribed volumes have survived. These are organized according to document type and country. The documents are arranged in the following sub-categories:

- sho / choku (詔・勅) – declarations announcing Ming and Qing dynasty events.

- reibu shi (礼部咨) – documents from the Chinese Department of Tributary Affairs bestowing diplomatic recognition on the Ryukyu Kingdom.

- Fukken fuseishishi shi (福建布政使司咨) – official correspondence from the provincial government in Fujian

- hyo / so (表・奏) – correspondence from Ryukyu kings to emperors of China

- kokuo shi (国王咨) – correspondence from Ryukyu kings to Li Bu (Chinese Department of Tributary Affair) or the local administration in Fujian

- fu bun (符文) – documents issued by Ryukyu kings authorizing travel to China

- shissho (執照) – documents providing leave to board vessels traveling to China

- kou kou bunko (弘光文稿) – correspondence between the Ryukyu administration and the southern regional administration of the Ming dynasty

- ryubu bunko (隆武文稿) – (as above).

- ii kaishi (移彝回咨) – diplomatic correspondence with Korea and other trading centers in East and Southeast Asia

- ii shi (移彝咨) – letters from Ryukyu kings destined for Korea and other trading centers in East and Southeast Asia

- ii shissho (移彝執照) – documents providing leave to board vessels traveling to Korea and the countries of Southeast Asia

- san nan o hei Kaiki bunko (山南王併懐機文稿) – records relating to diplomatic contacts between King Tarumi of San-nan (Ryukyu’s southern kingdom) and Ming dynasty officials, and correspondence between Minister Kaiki and port authorities in Palembang, Sumatra

The Second Collection (1697-1858)

The remaining 187 of the 200 volumes are arranged in chronological order, and provide a complete record of official communication between the Ryukyu Kingdom and Qing Dynasty authorities.

The Third Collection (1859-1867)

Copies of the entire thirteen volumes of the collection have survived.

The Additional Collection (1859-1867)

This collection contains documents relating to contacts between the Ryukyu Kingdom and the United Kingdom, France, and the United States of America, as well as inventories of goods imported on ukan-sen trading vessels from China.

Ryukyu Kingdom Foreign Policy

China

The documents of the Rekidai Hoan relate principally to the diplomatic relationship between the Ryukyu Kingdom and China, which developed from contacts initiated by Emperor Taizu in 1372. These initial contacts led to the subsequent development of an envoy-tribute (sappo-choko) relationship in which Ryukyu administrations offered loyalty and goods to the Chinese imperium in exchange for diplomatic recognition and external protection. As a result, the kingdom became a subordinate member of a regional security and trading alliance dependent upon Chinese military and economic hegemony

In practice, this system was dependent upon regular payments of tribute determined by the Chinese authorities in exchange for diplomatic recognition, which was embodied by the presence of Chinese envoys, or sappo, at key ceremonial occasions such as coronations. The relationship was also reinforced through academic links which provided opportunities for members of the Shuri court to study in China

Rather than destroying this system, the Satsuma invasion of 1609 gave rise to a system of dual subordination, and as a result, the tributary relationship with China continued to exert an important influence over the islands’ art, customs, legal and political systems, literature, and food, the legacy of which is apparent in many contemporary aspects of Okinawan culture.

Korea

Diplomatic links between the Ryukyu Kingdom and Korea were initially established as early as 1389, during the later years of Satto’s reign. Initially these contacts were restricted to the return of shipwreck survivors and victims of the notorious wako pirates. A significant record of these early contacts remains in the account of a Korean shipwreck survivor preserved in the extensive archives of the Choson Wangjo Sillok (the annals of the Choson Dynasty).

In the following decades, a small-scale tributary relationship developed between Korea and the Ryukyu Kingdom. This connection was stifled, however, by the activities of Japanese merchants and pirates whose activities deterred Korean traders from visiting the kingdom and served to underline the limited protection the Korean state could offer the kingdom. As a result, the incentives for both parties to enter a tributary compact were highly circumscribed. Peaceful relations were nevertheless maintained, and dignitaries bearing gifts from the Ryukyu Kingdom were often welcomed at the Korean court, and gifts were in turn offered to Ryukyu monarchs

Among the more notable of these was the Dai Zo Kyo, a venerated Buddhist scripture which was housed in Benzaiten do, a library dedicated to Buddhist sutras which was situated on a small island on Enkan pond at Shuri Castle. In return, the Ryukyu Kingdom offered entrepot goods from Southeast Asia. By the mid-fifteenth century, however, this incipient relationship had largely been supplanted for security reasons by contacts mediated through merchants based in Hakata or Tsushima in Kyushu. This proxy communication in turn provided a lucrative incentive for Kyushu based traders to present themselves as Ryukyu Kingdom officials when dealing with Korean clients.

“The Golden Age of the Ryukyu Kingdom”: The 14th to 16th Century

Southeast Asia

Merchant ships (manaban) from Southeast Asia became a familiar sight in the Ryukyu Kingdom during the latter half of the fourteenth century. In response, Ryukyuan traders began to engage in return expeditions. Records of these began to appear in the Rekidai Hoan in the fifteenth century, during which abundant references were made to contacts with Siam, Patani, Malacca, Palembang, Java, Sumatra, Vietnam, and Sunda. Pioneers of this trade were also accompanied on their voyages by letters containing the King’s seal and gifts in anticipation of establishing formal trade relations with sister ports.

The entrepot trade that subsequently developed involved the export of goods such as Japanese swords and gold, which were traded for ivory, tin, jewels, pepper, spices, and caesalpinia sappan for medicine or dyes, many of which were subsequently re-exported to China, Japan or Korea. Many of the Ryukyu Kingdom’s Southeast Asian trading partners shared a similar tributary relationship with the Ming Dynasty and as a result Chinese became a lingua franca for official communication and trade negotiations.

Japan

Although no record was kept in the Rekidai Hoan of correspondence with Japan (which was conducted in Japanese), a number of diplomatic and trade missions were dispatched to the Muromachi Shogunate during the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. These contacts were terminated, however, when the Shogunate was plunged into civil conflict during the second half of the 15th century, and commerce was redirected to the southern ports of Kyushu.

In spite of political instability, Japan remained an attractive destination for Ryukyuan merchants, both as a market for entrepot goods from China and Southeast Asia, and as a source of goods to re-export to these trading partners. In addition to these commercial contacts, the Ryukyu administration had also repatriated a number of Japanese shipwreck survivors and welcomed a number of visitors from Japan. Among these visitors to the islands was a group of Buddhist monks who subsequently made their homes in the kingdom and provided diplomatic assistance to the Ryukyu administration in their communications with Japanese authorities. The presence of the Japanese monks also established a degree of cultural influence, as some entered the priesthood and established temples. Such harmonious contacts were to end abruptly, however, as the brutal Satsuma invasion of 1609 effectively destroyed the relative autonomy the kingdom had enjoyed

Reconstructing the Rekidai Hoan

In spite of the destruction of all the original records, the transcripts contained in the current Rekidai Hoan remain an important source of information relating to the history and culture of the Ryukyu Kingdom and provide invaluable insights into the conduct of diplomatic relations with other regional trading centers and major regional powers during the period. The collective wisdom compiled in what remains of the original archive may also provide guidance to a new generation of Okinawans attempting to define a role for the islands in a new and changing international context

Those charged with the task of reconstructing the archive from the remaining transcripts have therefore been intensely aware of their responsibility to recreate an accurate version of the original collection. This task, however, has been greatly complicated by the abridged nature of the Kume collection from which all existing transcripts were drawn, as well as by imperfections in the surviving transcripts, which contain obscure sections and provide only a partial record of the Kume material.

Cyanotype photographs of Rekidai Hoan documents provide a faithful, if incomplete, record of the original documents, but at the same time reveal misprints, omissions, and effaced sections contained in the Kume archive, indicating the need for further research to reveal their full contents. The cyanotype copies also call into question the authenticity of transcripts which were not annotated, as the convention of inserting speculative sections without indicating their apocryphal nature complicates the task of distinguishing original and extraneous material. To achieve this, it has been necessary to conduct a painstaking comparison of the surviving transcripts.

The Annotation and Translation of the Rekidai Hoan

A further challenge facing those attempting to translate copies of the original documents is the variety of possible referents yielded by the obscure and literary Chinese in which they are written. As a consequence, even the task of distinguishing between the names of people, places, goods, official titles, and departments of state becomes a daunting one. Translators have also encountered difficulties arising from the variety of possible Japanese readings of the original Chinese Kanji and have therefore added annotations in order to draw attention to sections of the text which remain obscure. Therefore, in addition to the task of locating documents and reassembling the archive, researchers also face major linguistic challenges in interpreting its content.

Modern compilers have looked toward China, the recipient and source of most of the original correspondence, to provide information regarding obscure and omitted sections of the existing documents. Particular interest has focused on the First Historical Archives of China and the National Palace Museum in Taiwan, which, as well as helping to establish and confirm the chronological record of events during the period, have provided valuable historical information and insights into administrative systems which operated during the tributary era. Information gleaned from these archives has yielded details of matters relating to diplomatic protocol, documentary and archival conventions, administrative titles and the duties associated with them, and the names of individuals to which the original documents refer.

A further line of inquiry which has been pursued by researchers is the investigation of memoirs and official documents from the Ryukyu Kingdom preserved by the families of official dignitaries who were sent on missions to China and Southeast Asia. Such sources are now considered indispensable as a means of gaining greater insights into the original content of the documents.

Documents Held in Overseas Collections

The First Historical Archives of China house documents mainly from the Qing dynasty. They include limited correspondence from Ryukyu kings. The archive also records diplomatic visits and details of tributary payments which are considered of major significance to the work of recompiling the original record.

Documents preserved at various historical sites in the city of Fuzhou provide a valuable record of the diplomatic relationship which developed between the regional administration in China’s Fujian Province and the Ryukyu Kingdom. Among major sites of interest is the Ryukyu-kan, the diplomatic quarter of the city which was reserved for visiting Ryukyuan dignitaries in transit to Beijing (or Nanjing during the early Ming dynasty). The city itself is also of importance as a center of cultural exchange from which the binjin 36 sei experts, who would later play an important role in the diplomatic affairs of the Ryukyu Kingdom, emigrated. It is hoped that documents yet to be discovered at sites in the city may therefore provide valuable background material for those attempting to reassemble the archive.

Ryukyu-related sites in Chinese imperial centers such as the Kaido-kan, a government quarter reserved for visiting dignitaries, and the historic Kokushi-kan, a center of learning that provided education for the Ryukyu Kingdom elite, also offer important insights into Sino-Ryukyuan relations. It is also thought that broader research into the activities of other visitors to China from the Ryukyu Kingdom may prove significant.

Ryukyu-related documents held in South Korea and Southeast Asia, although far less numerous than the documents available in the Chinese archive, may reveal details of the trading culture which flourished during the “Golden Age”of the Ryukyu Kingdom between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries. An investigation of archives held in Southeast Asia, alongside the record documented in the Rekidai Hoan may, for instance, provide clues into the origin of such important cultural products as the distilled liquor awamori, which has become an important expression of Okinawan identity. An ongoing collaborative program aimed at sharing historical information with South Korean archivists is also likely to provide information regarding cultural and diplomatic relations between Ryukyuan and Korean dynasties.

Co-operation in Research and Recompilation

Before the task of recompiling the Rekidai Hoan began, Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education concluded an agreement with the First Historical Archives of China, establishing an exchange program to create Ryukyu-China academic links. As a result, the following bilateral initiatives were established:

- Okinawa and Beijing to host biennial symposia on the history of Ryukyu-China diplomatic relations. Parties agreed to take turns in hosting bilateral symposia in which the host country will invite five experts from its counterpart at the host country’s expense. This is to be followed by the publication in Okinawa of the contents of symposium discussions.

- Okinawa to invite two experts from China for seven days at the prefecture’s expense

- China to conduct research into Okinawa related articles from historiographical materials relating to the Qing dynasty and provide microfilm copies at cost

The joint undertaking with China to hold biennial symposia and to invite experts to investigate Ryukyu-related historiographical documents has led to the development of increased interest in the historical relationship between the Ryukyu Kingdom and China. In addition, through the work of compilation, Ryukyu historians and those engaged in related areas of study are gradually developing a greater understanding of the kingdom’s diplomatic policy. Such research has been made more widely available through the publication of Rekidai Hoan Kenkyu, a journal dedicated to the archive, as well as through the publication of symposia discussions. Ryukyu-related historiographical documents in the First Historical Archives of China have also been made available through regular publication, and further research is expected to uncover more material.

Another feature of the Rekidai Hoan project has been the development of bilateral relationships between researchers and administrative officials in Okinawa and China. In an increasingly internationalized society, this has provided a valuable opportunity for Okinawans to gain a deeper mutual understanding with their Chinese colleagues, and build closer relationships.

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 3: Nations and Other Stories. March 2003