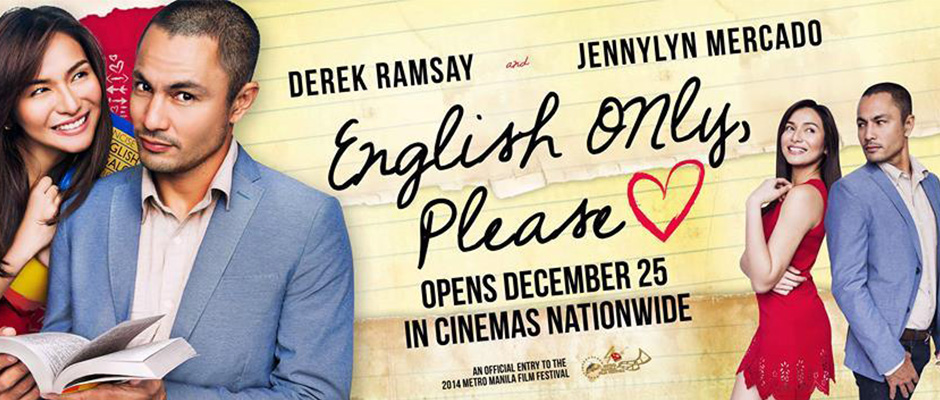

English Only, Please (2014)

Directed by Dan Villegas. Script by Antoinette Jadaone and Dan Villegas

Against such opinions, I want to show how one featured film in the 40th MMFF (2014), English Only, Please (EOP), is far from being brainless entertainment. The film is certainly entertaining, but being a Filipino romantic comedy does not keep it from impinging on critical issues in Philippine society: the meaning of Filipino, the intimate link between language and identity, the hopelessness and lack of prospects in the Philippines, and Filipinos’ dreams of a better life. It also captures the ambivalence that many Filipinos feel towards their homeland. EOP speaks of loving the Filipino, but also portrays Philippine society in a negative light, offering good reasons to leave the country.

Accommodating Filipinos Abroad: Migration, Identity, and the Government’s policy

EOP revolves around the romance between Julian Parker, a Filipino-American business analyst from New York, and Teresa “Tere” Madlansacay, a Filipina who agrees to help Parker translate a letter from English to Filipino. 2He also wants Tere to coach him in delivering the missive in proper Filipino (accent, tone, and pronunciation) to his ex-girlfriend, whom he fell in love when she was studying the United States. She had broken up with him, and Parker flies to Manila to let her have a piece of his mind. The letter contains the bitter sentiments of a jilted lover.

The film, however, is not just about two people falling in love but also about a Filipino (—foreigner) coming to love his homeland and part of his heritage, a motif that finds resonance in official government discourse on Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) and Filipino immigrants. This discourse essentially considers these Filipinos as part of the nation, constructing and maintaining their links – social, economic, affective, etc. – to the homeland.

Aware of their vital contributions to Philippine society, the Philippine government labeled many OFWs as “Bagong Bayani” (New Heroes) and pushed in 2003 for a dual citizenship law. The Citizenship Retention and Reacquisition Act allowed Filipino immigrants to reclaim their Filipino citizenship and incur all the benefits and responsibilities thereof. As Filipino citizens (once again), Filipino migrants can own as much land and invest in businesses, among other perks, all of which would be harder or impossible to do for foreign citizens. The law has boosted the government’s efforts in securing and capitalizing on the remittances and investments of Filipinos abroad.

The Philippine government also established the Commission on Filipinos Overseas (CFO), which promotes diaspora-to-development programs that include technology transfers and livelihood projects. These initiatives tap Filipino migrants to help develop the economy, provide jobs, share expertise, and enhance the well-being of Philippine society. Accommodating Filipinos abroad within the Filipino nation has an overall objective: to renew and benefit from their ties to the Philippines. The government sees them as part of the Filipino nation, 3 whatever their citizenship may be, and many of them do not need a law to identify with the Philippines.

In the film, Parker’s homecoming is part of this overall discourse of accommodating Filipino-foreigners within Philippine society. Born in the United States of a Filipino mother and an American father, he is a U.S. citizen, but later speaks of having “Pusong Pinoy” (Filipino at heart). Indeed, EOP charts Parker’s transformation from a cold, broken-hearted business analyst who doesn’t care at all about the Philippines to a gentleman who falls in love with a Filipina and speaks Filipino with a foreign accent. In a Skype-chat, his father tells him, “It’s hard not to love the Philippines, di ba (isn’t it)?” By this time, he has fallen in love not only with Tere but also with the country.

[youtube id=”saSCtoEBpeI” align=”center” mode=”thumbnail”]

Learning Filipino, Loving the Philippines

This falling in love with the Philippines is framed within the story of Julian’s learning to deliver his letter in Filipino. But this is not just about picking up a language but also about coming home and becoming/ embracing his Filipino heritage. And the film, as it were, translates not only English words into Filipino, but also an American(ized) identity into a Filipino one.

But what is Filipino, and how does EOP portray it? As far as Parker is concerned, being Filipino is marked by the ability to speak the language. In one scene, he is asked why, even though he looks Filipino, he cannot speak Filipino. And he specifically has to learn its colloquial version, which is filled with colorful phrases such as mot-mot (motel); kita-kits (a twist on ‘kita-kita tayo,’ meaning, ‘we’ll see each other then’); taralets (a Filipino colloquialism for ‘let’s go’); and haliparot (flirtatious).

To leave no doubt that he is embracing Philippine society and a Filipino identity, EOP also has him fall in love with a Filipina, who has an unambiguously Filipino surname, Madlansacay. She could have had other last names like Cruz or Reyes, but these are Spanish ones; 4 and the film wants us to see her as unmistakably Pinay (colloquial term for a Filipina). Moreover, Tere embodies someone that many Filipinos can identify with: the daughter who dutifully sends money home and who to a fault sacrifices her personal well-being for others.

Migration and The Culture of Dependence in the Philippines

It may be hard not to love the country, but EOP also subjects it to an unflattering critique, which is especially seen in its portrayal of men. Rico, Tere’s pseudo boyfriend, only wants sex out of the relationship; and her brothers, who seem to be perpetually unemployed, spend their time lounging around, playing card games, and having regular drinking sessions with the neighbors. Even worse, they rely on Tere for money.

In contrast, Tere is pictured as a dutiful daughter who sends money back home without fail. Sadly, however, her hard work has not paid off; her family’s house has barely been renovated. She is disappointed over this state of affairs, but she justifies her hard work for and devotion to her family. Unable to finish nursing school 5 she feels obligated to be the primary breadwinner. The audience may accept Tere’s rationalizations, but one can’t help feeling that nothing would come out of her present life.

Nonetheless, EOP saves our heroine by sending Parker. The film does not say so directly, but Tere, the smart, hardworking and pretty young lady, comes to know a much-deserved better life through and because of him. Unlike the other men in her life, Parker seems to be a responsible man and would be able to offer Tere a happier, much rewarding life in New York than in Bulacan – assuming of course, they get married.

There is also no explicit talk of migration in EOP, but it touches on it all the same. By highlighting Tere’s fate and giving her the opportunity to meet Parker, the film indicts Philippine society for its lack of progress, and sees (marriage) migration, like so many Filipinos, as the road to a better life. Like Tere, many of them work hard in the Philippines without really improving their lot. They see little opportunity for personal (and social) progress in the country, and that it would be more practical to migrate and/or marry a foreigner in order to escape a life that does not seem to advance.

We can assume that Parker and Tere eventually get married and settle in New York. But this would hardly solve the problem that the film portrays, since it would precisely be all the more reason for her family to depend on her and her husband. After all, as dollar earners, both could send more money to Bulacan, but given what we’ve seen of Tere’s brothers, would this really help? Or would her migration to New York simply reinforce what has been called a culture of dependence among the recipients of remittance in the Philippines?

Ambivalence about the Nation: Love the Filipino, Leave the Philippines

The downside of Filipino migration is that it creates complacency among those left behind. As in the case of Tere’s siblings, there is little incentive to work since someone in the family can simply send money home. This complacency exacerbates the lack of economic opportunity that drives migration in the first place. Thus, much to their resentment at times, many OFWs are the sole breadwinner of their families, even second-degree relatives, in the Philippines. It would be easy for Tere to simply cut her ties to her family and live her life in New York. But this would be unthinkable for Filipinos like Tere, who are less individualistic and think highly of family.

Tere does not confront her family about the way they waste the money she sends. Like its heroies, EOP too ignores the heart of the matter, falling back instead on romantic love and migration, to address an underlying problem. Like all romantic comedies, EOP ends happily ever after. But does it really in the greater, post-film scheme of things? Perhaps it might have been better if Tere had reprimanded her family about how they handled the money she kept sending. And if she asked her brothers to find jobs, she wouldn’t need to work so hard, and there may be less need to migrate. But this might mean a different film altogether, and it would not have been the same EOP, the highly entertaining romantic comedy that became a blockbuster hit.

Reviewed by Janus Isaac V. Nolasco

University Researcher, Asian Center

University of the Philippines Diliman

Issue 17, Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, March 2015

Notes:

- The Metro Manila Film Festival started in 1975 and is held from 25 December to early January, during which no foreign film is shown in theaters across the country. ↩

- The film stars Derek Ramsay as Julian Parker and Jennylyn Mercado as Teresa Madlansacay. ↩

- I owe this point to Professor Aguilar, who discusses Filipino identity and migration in his book Migration Revolution. ↩

- Filipinos obtained Spanish surnames because of a decree in 1849. They were asked to choose one from a list. The “madla” (mass as in ‘mass production’) in Tere’s last name puts a touch of the everyman in her. ↩

- Filipinos dominate the global care industry, working as nurses, caregivers, and other related fields. ↩