Recent reports from Freedom House, 1 IDEA, 2 and Reporters Without Borders 3 have shown that there has been a problem with shrinking civic space within Indonesia’s digital realm. These reports also align with the national report from the Indonesian National Human Rights Institution and the Kompas daily survey of 2020 that showed that 36 percent of Indonesians felt insecure in expressing their opinions on social media. 4

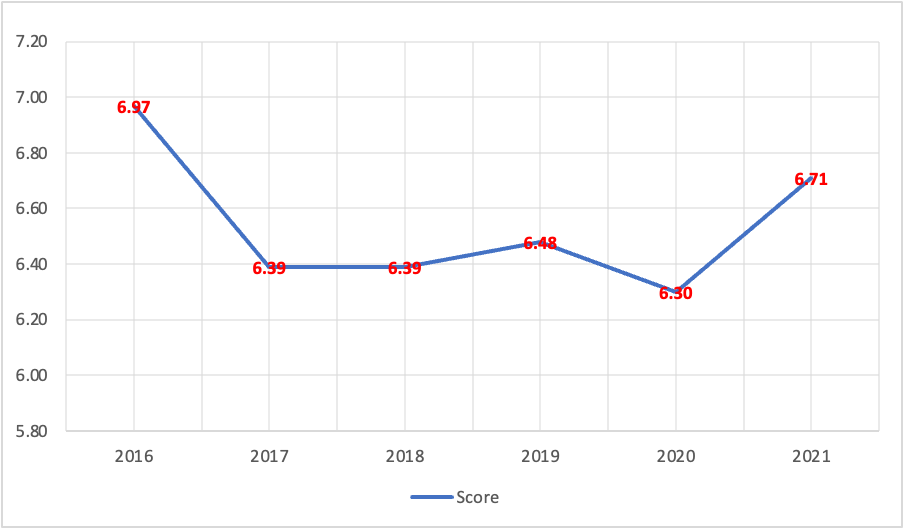

Data source: The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021

With 204.7 million internet users (January 2022), or at least 73.7 percent of the total population, 5 Indonesia has steadily become more authoritarian since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the government using terms such as “guarding national security” and “creating stability” to justify the implementation of new and repressive legislation for the country’s digital sphere. 6 According to SAFEnet’s 2020 Report, Indonesia had experienced worrying developments in three key areas related to digital authoritarianism: surveillance, censorship and repression, and internet shut-downs.

Surveillance by the State in the Digital Realm

After the pandemic started in Indonesia in March 2020, President Jokowi instructed state intelligence bodies to strictly maintain public order. Simultaneously, the President and his government continued to promote tourism in the country, saying that Indonesia was safe to visit and that the Corona virus would not spread in the country due to Indonesia’s tropical climate. A month later, police started to actively control the narrative surrounding the pandemic, particularly on social media. Police order No. ST/1100/IV/HUK.7.1.2020, dated April 4, 2020, provided the police with emergency powers to carry out ‘cyber patrols’ and to monitor online discussion, targeting: those accused of spreading misinformation related to COVID-19, or the government’s response to the pandemic, or even criticism of the president and government officials managing the crisis. Another order was issued on October 2, 2020, with an instruction to provide counter-narratives and oppose digital protests or campaigns carried out by civil society groups against the Job Creation Law in late 2020.

The virtual police were introduced in February 2021. This new unit was provided with the power to send a virtual alert to netizens as a warning before arresting them. This virtual alert consists of a warning and an order to delete whichever post has been reported to the police. Between 23 February and 11 March 2021, the virtual police sent 125 Virtual Alerts and detained 3 people. The emergence of the virtual police has made self-censorship more common in Indonesia. If a person is reported for saying something inappropriate, the police immediately provide them with instructions to delete that post. This has created a climate of fear concerning the country’s digital realm.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a contact tracing app named PeduliLindungi was released at the end of March 2020 by Indonesia’s Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (MCIT) and the Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises (MSOE) to track exposure to COVID-19. A privacy audit rolled out by DigitalReach 7 and CitizenLab 8 found out that PeduliLindungi Version 2.2.2. (when using Bluetooth) could send out a users WIFI information, MAC address, and also the local IP address. Overall, the app provided the authorities with a high level of information about a person’s movements. Although another version of PeduliLindungi was later introduced, there were still data protection issues for users. Other apps released by the government related to contact tracing and the COVID-19 pandemic later came under scrutiny for their data collection practices.

Repression and Censorship in the Digital Realm

The existing internet law in Indonesia (EIT Law) has become a weapon that is very often used to silence those who criticize government policies, although it is also widely used by other groups, such as politicians and businessmen. This law is not only directed at individual critics, but also against human rights activists and journalists, especially journalists who investigate the impact of development on the environment.

This COVID-19 pandemic created an opportunity for law enforcement officers, who used the emergency situation to stifle expression in the digital realm by using the EIT Law and similar regulations. Using this draconian law, activists who used their social media account to protest have been prosecuted using legislation related to hate speech and online defamation, or even treason in the case of Papuan activists.

The Indonesia National Human Rights Commission (Komnas HAM) stated that in the 2020-2021 period, most cases of violations of freedom of expression occurred in the digital sphere. 9 During the COVID-19 period, Komnas HAM received numerous reports of hacking activities against critics in the media and civil society organizations. An example of this was an attack on the online news outlet – Tirto.id – which was hacked by an unknown cyber-actor, who later removed or deleted certain news articles, particularly articles criticizing COVID-19 medication that was made by Indonesian government bodies.

Data Source: SAFEnet Digital Rights Situation Report: 2020-2021

Technological oppression in the form of cyber attacks has reportedly become more common in Indonesia since 2020. According to SAFEnet’s digital rights situation report for 2020, at least 147 cyber attacks occurred in 2020, with 41 incidents in October 2020 alone. This is a huge increase from 8 incidents per month in previous years. 10 Almost all of these digital attacks were related to parties who had criticized government policies on the various issues mentioned above. For 2021, the number of digital attacks rose to 193 incidents in total, with an average of 16 incidents per month. 11

Internet Shut-Downs

An Internet shut-down, as explained by AccessNow, is an intentional disruption of the internet, or of electronic communications, rendering them inaccessible or effectively unusable, for a specific population or within a location, often to exert control over the flow of information. 12 While OONI (Open Observatory of Network Intervention) defines online censorship like blocking apps or blocking particular websites, as a form of internet shut-down, or partial shut-down.

In August 2019, the Jokowi administration exhibited its authoritarian tendencies in its approach to disturbances in Papua province. Not only were repressive measures used by the security forces, but the Jokowi administration also decided to implement a full internet shut-down to support its military clampdown. This was the first time that the Indonesian government implemented a complete internet shut-down: the government shut down the internet in Papua for 338 hours, starting with a slowdown of the internet on 19-21 August 2019, followed by a complete internet shut-down on 22 August to 4 September 2019, under the pretext of preventing the spread of false information in Papua and West Papua.

In 2020, there were 4 reports of alleged bandwidth throttling (partial shut-downs) being re-imposed on Papua and West Papua provinces. 13 In 2021, there were another 12 internet outages. 8 of them were allegedly internet shut-downs directly related to Indonesia military operations. 14

Online Manipulation

A Universitas Diponegoro 2019 report, 15 later followed by the KITLV-LP3ES-Undip-ISEAS report in 2021, both reveal that the Government of Indonesia used cyber mercenaries for supporting their repressive policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cyber mercenaries, 16 as defined within the Indonesian context, are a fluid networks of buzzers, coordinators, influencers, content creators and political consultants, who work together to manipulate public opinion through social media by creating a certain narrative on certain political issues. The funding of this cyber gang came from individual politicians, political parties, and business people. 17

The operation of cyber mercenaries and the manipulation of public opinion was aimed at manufacturing consent for the unpopular policies introduced throughout the COVID-19 period by spreading hoaxes and fake news, together with the doxing and trolling of government opponents. 18

The Indonesian government has been successful at co-opting the Indonesian digital public sphere and has prevented it from becoming a free space where the voice of civil society activists can be heard. Therefore, the manipulation of public opinion online by cyber mercenaries can be seen as one of the more worrying signs of the rise of digital authoritarianism in the fourth largest country in the world.

Taking into account all of the developments outlined above, Indonesia is slowly but surely drifting toward greater digital authoritarianism. Although civil society activists and the younger generation in Indonesia are pushing back against this growing authoritarianism, the future is uncertain and it is unclear whether Indonesia can reverse the democratic roll-back it has experienced since the mid-2010s.

Damar Juniarto

Damar Juniarto is the Executive Director and co-founder SAFEnet (Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network).

Top banner: Jakarta, Indonesia-June 2021-Police and TNI officers wear hazmats during the operation of the COVID-19 hunting team. Photo: Wulandari Wulandari, Shutterstock

Notes:

- Freedom House, Freedom on the Net 2020: Indonesia, https://freedomhouse.org/country/indonesia/freedom-net/2020 ↩

- IDEA Global State of Democracy, 2019, https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/global-state-of-democracy-2019 ↩

- Reporters Without Borders’ (RSF), Indonesia, 2021, https://rsf.org/en/indonesia ↩

- Survei Komnas HAM Refleksi 20 Tabun Undang-Undang Hak Asasi Manusia https://www.komnasham.go.id/index.php/laporan/2020/02/14/61/survei-komnas-ham-refleksi-20-tahun-undang-undang-hak-asasi-manusia.html ↩

- Data Reportal Indonesia 2022, last modified 18 February 2022, https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-indonesia ↩

- Damar Juniarto, “The Rise of Digital Authoritarianism in Indonesia”, ASEANFocus, Issues 4/Dec 2020 page 13, https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/ASEANFocus-December-2020.pdf ↩

- Digital Reach, Digital Contact Tracing Indonesia, 2020 https://digitalreach.asia/digital-contact-tracing-indonesia/ ↩

- CitizenLab, An Analysis of Indonesia and Philippines governmenrt launch Covid-19 apps, 2020 https://citizenlab.ca/2020/12/faq-an-analysis-of-indonesia-and-the-philippines-government-launched-covid-19-apps/ ↩

- Indonesia National Commission of Human Rights, Annual Report 2019, https://www.komnasham.go.id/index.php/laporan/2020/12/09/76/laporan-tahunan-komnas-ham-2019.html ↩

- Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network, Digital Situation Report in Indonesia 2020: Digital Repression Amid The Pandemic, https://safenet.or.id/2021/05/digital-situation-report-2020/ ↩

- Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network, Digital Situation Report in Indonesia 2021: The Pandemic Might Be Under Control, But Digital Repression Continues, https://safenet.or.id/2022/03/in-indonesia-digital-repression-is-keep-continues/ ↩

- AccessNow, “No Internet Shutdowns, let’s keep it on”, https://www.accessnow.org/no-internet-shutdowns-lets-keepiton/ ↩

- Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network, Digital Situation Report in Indonesia 2020: Digital Repression Amid The Pandemic, https://safenet.or.id/2021/05/digital-situation-report-2020/ ↩

- Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network, Digital Situation Report in Indonesia 2021: The Pandemic Might Be Under Control, But Digital Repression Continues, https://safenet.or.id/2022/03/in-indonesia-digital-repression-is-keep-continues/ ↩

- Wijayanto, Ph.D, Dr. Nur Hidayat Sardini, Gita Nindya Elsitra, Orisa Irhamna, Laporan Penelitian Menciptakan Ruang Siber yang Kondusif Bagi Pegiat Anti-Korupsi, Universitas Diponegoro 2019 ↩

- Inside Indonesia, “Cyber Mercenaries vs The KPK”, last modified 2022, https://www.insideindonesia.org/cyber-mercenaries-vs-the-kpk ↩

- Inside Indonesia, “Organisation and Funding of Social Media Propaganda”, last modified 2022, https://www.insideindonesia.org/organisation-and-funding-of-social-media-propaganda ↩

- Inside Indonesia, “The Threat of Cyber Troops”, last modified 2022, https://www.insideindonesia.org/the-threat-of-cyber-troops ↩