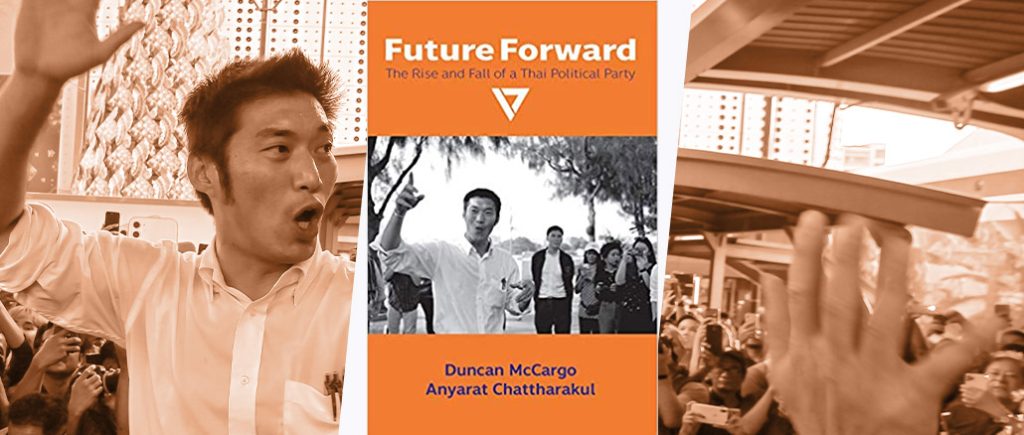

Future Forward: The Rise and Fall of a Thai Political Party

Duncan McCargo, Anyarat Chattharakul

NIAS Press, (2020)

In what way did mostly reformist youths seek to rejuvenate Thailand’s parliamentary politics in 2019-2020? How successful did this attempt prove to be? Future Forward: The Rise and Fall of a Thai Political Party addresses these questions. Authors Duncan McCargo and Anyarat Chattharakul have each previously written about contemporary Thai politics—Chattharakul is also a former Thai diplomat. This book represents an appraisal of Thai democracy in an age where monarchy and military remain dominant actors across a country suffering from a deep political division.

In the Forword, the authors introduce Future Forward party (FFP) as a parliamentary “upstart (1)” before narrating a history of events prior to the 2019 election. Despite the 1932 overthrow of monarchical absolutism, Thailand became beset by a weak democracy existing in the shadow of a powerful monarchy and military. The latter ousted elected populists Thaksin and Yingluck Shinawatra in 2006 and 2014 respectively. FFP succeeded in the 2019 polls because it was new, vibrant and benefited from the pre-poll judicial dissolution of Thaksin’s Thai Raksa Chart party.

Chapter 1 examines FFP’s party leadership. The authors describe party leader Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit as a “hyperleader,” a term coined by Gerbaudo (12). FFP appeared to oscillate around the personality of Thanathorn, a young, handsome, charismatic, progressive billionaire. FFP’s Secretary-General, Piyabutr Saengkanokkul was a young, liberal legal scholar who, when Thanathorn was barred from taking his seat on the first day of parliament in 2019, became FFP’s parliamentary leader. Pannika Wanich, a former anchor and journalist, became FFP’s spokesperson. She added gender diversity to the party. Thanathorn’s friend Pita Limjaroenrat became the leader of Move Forward Party (MFP), the successor of FFP, following FFP’s dissolution. All of these leaders shared a youthful vitality which appealed to many voters.

Chapter 2 focuses on Thais who voted for FFP in the 2019 election. Social media promoted Thanathorn as a sexy, trustworthy, father figure adored by youth (50). But FFP won votes (mostly in Bangkok) using messages of anti-dictatorship and fighting for social justice. Electioneering relied mostly on volunteers, social media and political rallies (71). Vote-buying was not an FFP tactic. FFP supporters were not only Bangkok’s youth: the party had followers among all ages and from all regions. Using energetic campaigning and digital marketing, FFP sold itself to voters as a brand-new alternative to the humdrum, divisive, corrupt authoritarian-dominated politics of old.

Chapter 3 focuses on FFP as a party. It describes Thanathorn and FFP as the third failed attempt in which Thai party leaders and their parties were “transformational” rather than “transactional (107-109).” FFP was part of a very recent generation in political parties which switched from being “electoral professional” to being what Gerbaudo calls “digital” or “platform” parties because they actively used social media to advertise their policy platforms (110-112). FFP’s founders emphasized that it was a diverse, new generation party which represented a plethora of democratic, broad-based objectives. Though not a legal requirement, FFP used primaries to select candidates, demonstrating internal party democracy. For money, it used internet crowd funding and selling branded merchandise but eventually relied on loans from Thanathorn. Following FFP’s success in becoming the second largest opposition party, it became the leading parliamentary critic of the military and ruling coalition and was well-skilled in debates. But the palace-centered powers-that-be had had enough. Eventually, in November 2019, “lawfare” was applied: the judiciary disqualified Thanathorn as MP and in February 2020, dissolved FFP—for legally ambiguous reasons. At the same time, as FFP descended toward its end, Thaksin’s Pheu Thai party did not join it in a censure of the military-dominated government.

The authors conclude by stating that FFP’s demise gave rise to its parliamentary successor MFP (led by Pita) and the creation of FFP’s non-parliamentary political entity, the Progressive Movement (PM). Not surprisingly MFP’s smaller size (resulting from FFP defections when it was dissolved) and its less charismatic leadership have prevented it from being as effective an opposition voice as was FFP. PM was more successful, using online media and laser projections to spread its message. PM’s arsenal of hi-tech tools has succeeded in organizing and communicating peaceful resistance. The authors offer four future scenarios. First, Thanathorn and his supporters will eventually lead a democratic opening that subordinates the military and reforms monarchy. Second, nothing changes, as the monarchy, military, and judiciary maintain the status quo. Third, pandemonium erupts with the country violently divided. Finally, Thailand’s old order succeeds not only in maintaining physical control but forcing reluctant compliance by all political challengers.

This study has several strengths. First, it is the first book to analyze a new type of political party elected to parliament in the first election in Thailand since 2014. Second, it interestingly examines a youthful, vibrant, collegial “hyper”—party leadership rarely seen before in any country. Third it focuses on changing patterns of voting behavior and how FFP innovatively sought to influence voters’ perceptions. Fourth, this book utilizes a fresh, unorthodox approach to methodology, using “digital ethnography (173).”

The authors could have mentioned that FFP was not entirely distinctive from other Thai political parties in 2019 with regard to relying on digital marketing. Also, it was simply the latest in a long line of Thai leader-centered parties—including Thai Rak Thai, Chart Thai, Kwam Wang Mai, Kit Sangkom, Nam Thai, Palang Dharma, Prachakorn Thai, and Muanchon. Moreover, the book could have offered a much more expansive review of literature on political parties in theory and in Thailand. Finally, the authors might have stressed how effects from Thailand’s 2019 electoral formula of Multi-Member Apportionment benefited FFP in terms of gaining seats as a result of “hanging votes” in Bangkok. 1

Regardless of criticisms, this book clearly, innovatively and insightfully presents a rich analysis of the evolution of a novel form of political party which, despite its 2020 dissolution, continues to resonate as an active and popular political entity today—with the Progressive Movement even fielding candidates in December 2020 local elections (local level candidates are not formally required to be party members). The judiciary’s February 2020 demolition of FFP played a major role in bringing dissent to the streets in mid to late-2020 where youth-led demonstrations demanded immediate democratic and monarchical reform. With this in mind, this book’s concentration on FFP’s role in helping to boost the vigor of young Thai reformers represents an important read for those seeking to comprehend the current and future shaping of Thai democracy.

Reviewed by Paul Chambers

Center of ASEAN Community Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Naresuan University

Notes:

- Waitoolkiat, Napisa, Chambers, Paul. “Battlefield Transformed: Deciphering Thailand’s Divisive 2019 Poll in Bangkok.”Thai Data Points, June 7, 2019, https://www.thaidatapoints.com/post/battlefield-transformed-deciphering-thailand-s-divisive-2019-poll-in-bangkok ↩