Hong Kong has the highest income inequality among the developed economies of the world and worryingly this discrepancy is still increasing. While the Gini coefficient, which measures inequality, was already at an alarming 0.52 in 1996, that number had increased to 0.54 in 2011. This can be partially blamed on a business-dominated undemocratic political system which accords disproportionate power to the tycoons while neglecting the massive number of poor. Labor unions are extremely weak and unable to achieve much for their employees, who fear that striking could make them jobless in a highly competitive environment. Many people live in extremely crammed environments including cage homes that are so tiny it is impossible to sit upright. Recent measures to combat the problem such as the introduction of a minimum wage and the setting of an official poverty line have done little to stem the problem. This is due to the fact that these measures are highly insufficient as for instance the minimum wage of HK$30 (as of December 2014) is not enough to afford food and housing.

However, despite the massive inequality, protests for democracy in Hong Kong are neither driven by those worst affected nor are they primarily about economic equality. Instead, the principal goals are maintaining the high degree of civil liberties and creating democratic institutions to protect them. The democracy movement is largely rooted in the highly educated middle income groups. As such, it can be traced to the pressure group politics of the 1970s, which was largely driven by professionals. Social concerns only gained in prominence after the handover as the introduction of proportional representation led to the emergence of many new parties. Meant to weaken the once powerful Democratic Party, this led to many deep divisions within the pan-democratic camp over goals and strategies. Some pan-democratic parties nowadays call for more economic redistribution, which has increased the worries among business tycoons about the adverse impacts of democratization on their interests. For instance, on Oct. 20, 2014, the chief executive, a former businessman, said he was worried about having to represent “half of the people in Hong Kong who earn less than US$1,800 a month”. 2

The primary underlying factors driving the movement have therefore not been directly related to inequality but rather to the declining social mobility and worsening quality of life, 3 which affect those in the middle the most. In 2003, the inability of the government to deal with these problems were combined with the fear that even the civil rights, which are core values of Hongkongers, could be lost. It was triggered by the government’s proposal to pass security legislation under Article 23 of the Basic Law, which threatened to undermine freedom of speech and assembly. As a consequence, an estimated 500,000 people joined in a massive rally through the central areas of Hong Kong island. The government eventually shelved the law and one year and another massive protest later, Tung Chee-hwa, the chief executive, also resigned.

For many people, protesting in the streets became the only possible channel to influence the political decision-making process. Every year, there are many small and big protests. Besides the massive annual July 1st rally, there are also the January 1st rally and the June 4th candlelight vigil. The latter is conducted every year to commemorate the victims of the Tiananmen massacre in 1989. In addition to these annual events, many protests have been organized more spontaneously such as the anti-Express Rail Link protests of 2009 or the anti-national education protests of 2012. Both of these protest movements signal the return of youth activism, which is driven by social media and a growing awareness of socio-political issues. These protests also reflect a growing Hong Kong identity. Driven by deep cultural, economic and political differences, many Hongkongers see themselves alienated from the mainland while simultaneously negatively impacted by the massive influx of both Chinese migrants and tourists. Because they have contributed to the rising living costs, it is perhaps not surprising that some have vilified them as “locusts.”

The recent Umbrella Movement has some things in common with previous pro-democracy protests. The main drivers behind the call for real democracy came from both students and academics, who were frustrated by the very slow progress of political reforms and deeply worried about the future of the city. The vast majority of participants were from middle income groups and not from those most affected by the deep social problems. In fact, a city-wide worker’s strike, which was proposed by pan-democratic labor organizations, never materialized. The reality is that most workers rely on their meager salaries for survival and are not willing to risk their own jobs. The income inequality thus mattered more as a concern among academics. Much more close to the hearts of the activists was the fact that opportunities for upward mobility have become rare and housing costs make it very difficult to have a better life than previous generations.

The movement also differed in one important aspect from most previous protests. Instead of emphasizing economic concerns, the Umbrella Movement epitomized the rejection of materialism and the money-making culture. It aspired to more idealistic goals such as the development of a truly democratic community in which people trust each other. A number of noteworthy events highlight this character of the movement. While the annual pro-democratic protest on 1st of July is used by many political parties and non-governmental organizations to collect donations, this was not the case in the two-month occupation. No one sold anything and people gave away stickers or postcards for free. Even the T-shirts and umbrellas were sold at production costs. In addition, you could get free water, snacks, or hot soup from supply stations. Many Hongkongers who did not dare to participate, donated large amounts of resources for the supply stations that supported it.

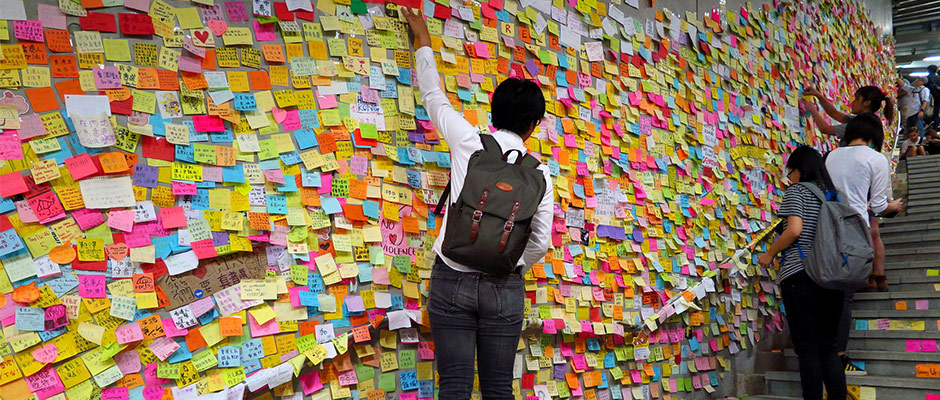

Another important difference was the fact that the Umbrella Movement was a site that stressed arts and handicrafts, which are generally held in low regard by the money-oriented society. Because the government has primarily focused on what it considers the four key pillars of the economy (financial services, trading and logistics, tourism, as well as producer and professional services), manufacturing and cultural industries have been neglected. In the main protest site, called Umbrella Square, volunteers erected a self-made study corner as well as a network of passageways for easier access. Yellow ribbons made out of leather were produced as well as T-shirts were printed with Umbrella themed logos for which people stood in long lines. Finally, impressive installation art and drawings of all kinds were displayed. These artworks dealt with underlying issues, such as the social problems, as well as the need to keep faith in a better, democratic future.

A key characteristic of the movement was moreover its educational nature. A group of professors and lecturers offered free lectures which began already during the student boycott in late September. During the occupation, the “democracy classroom” moved to the streets. The more than 110 different talks primarily focused on topics related to the movement including democratic politics, liberties, civil disobedience, as well as comparative perspectives. This aspect of the movement demonstrated the attempt to create a more sophisticated citizenry that is more aware of its rights and why those are important for the future development of the city.

While a great deal of the activity was concentrated on the three main protest sites, there was also an attempt to expand the movement into the larger society. The most prominent attempt was the use of a gigantic yellow banner, which was placed on Hong Kong’s landmark Lion Rock, an iconic mountain that can be seen from most of Kowloon. This was, however, not only an attempt to increase visibility but also an attempt to redefine the core meaning of the Hong Kong identity. In the 1970s, the mountain was seen as synonymous with the can-do spirit of Hongkongers, who can overcome any difficulties to climb the social ladder. The group announced in their Youtube video that “We think the spirit of Lion Rock isn’t just about money…the people fighting for universal suffrage all over Hong Kong have shown great perseverance in their fight against injustice and perseverance in the face of difficulties. This is the true Lion Rock spirit.” 4 With other words, Hongkongers are aiming for more than merely economic success to develop a democratic society that respects everyone.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The most obvious example of the anti-materialist bent of the protest movement was the most recent form of protest, the so-called “Shopping Revolution” which has driven hundreds of people to participate in unorganized but peaceful resistance protests almost every night. The movement emerged after the clearance of the Mongkok protest site. Inside the rugged shopping district, the protesters meet at the same movie theatre every night around 8pm and then proceed their “shopping” tour along Sai Yeung Choi Street, which is a very busy shopping street. It includes the frequent chanting of slogans, the use of yellow banners that call for democracy, and slow walking and tossing of coins and picking them up again. This form of protest emerged when CY Leung announced that, after the clearance of the protest site, people should go back to shopping, which had triggered the memory of a Chinese mainlander who had been interviewed by the media during an anti-democracy protest and had said that she was in Hong Kong for shopping. The protesters then upended this and went protesting that appears like shopping. As a result, hundreds of policemen are deployed every night in the area.

In conclusion, Hong Kong’s regime change is driven mainly by people in the middle income groups, who are worried about the future of the city. Economic concerns such as the high housing costs and the living expenses clearly play an important role but they are less important than more idealistic values such as personal liberties and democratic rights. The Umbrella Movement has been markedly anti-materialist and grassroots democratic as many participants were striving for something more valuable than financial wealth. At the same time, the majority of Hongkongers are still trapped in low-paying jobs with extremely long working hours, which has created significant barriers for more broad-based support. And even if they could be mobilized, the democratization process still depends on the willingness of the Chinese government to allow the necessary reforms. At the moment, this unfortunately seems unlikely.

Stephan Ortmann

Assistant Professor

City University of Hong Kong

Issue 17, Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, March 2015

Notes:

- The Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress decided that only allow two to three preselected candidates would be allowed to run for chief executive. ↩

- Ken Brown, “Hong Kong Leader Warns Poor Would Sway Vote,” The Wall Street Journal, 20 October 2014 <http://www.wsj.com/articles/hong-kong-leader-sticks-to-election-position-ahead-of-talks-1413817975> (accessed 17 December 2014). ↩

- Liyan Chan, “Beyond The Umbrella Movement: Hong Kong’s Struggle With Inequality In 8 Charts,” Forbes, 8 October 2014 <http://www.forbes.com/sites/liyanchen/2014/10/08/beyond-the-umbrella-revolution-hong-kongs-struggle-with-inequality-in-8-charts/> (accessed 17 December 2014). ↩

- Isabella Steger, “Pro-Democracy Banner Occupies Hong Kong’s Iconic Lion Rock, Spawns Memes,” The Wall Street Journal, 23 October 2014 <http://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2014/10/23/pro-democracy-banner-occupies-hong-kongs-iconic-lion-rock-spawns-memes/> (accessed 17 December 2014). ↩