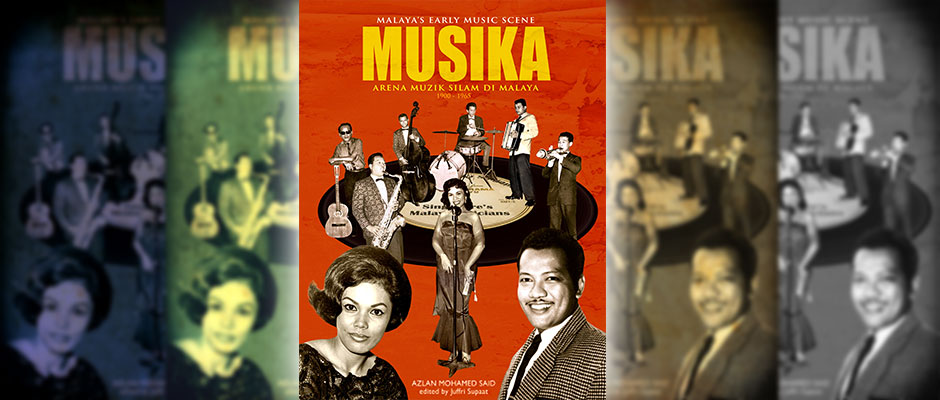

Muzika: Malaya’s Early Music Scene, 1900-1965.

Azlan Mohamed Said, edited by Juffri Supa’at.

Singapore: Stamford Printing, 2013. 256 pages.

The bilingual book in English and Malay is bound as an A4-sized paperback in full colour; necessary for the wealth of photographs that occupy its pages. In fact, readers could purchase the book for the images alone as most of them are rare photographs sourced from the personal collection of Azlan’s father and his colleagues. Unlike most depictions of music and musicians from this era, these are not images that you would find in commercial Malay-language film and music magazines. Unfortunately for scholars, specific dates and sources for most of the images are not stated. It could be that the dates for some photographs may have been forgotten by the owners themselves. Moreover, as some of the images are from private collections, the authors may be obscuring them upon the request of the owners. Nonetheless, the photographs reproduced in the book are important cultural documents and much can be gleaned from them. In addition, the photographs are credited to their contributors at the end of the book (p.248).

I am particularly struck by a photograph captioned ‘traditional Malay music ensemble’ dated ‘1947’ (pp.16-17). Readers will see fourteen young women, all are sitting in the front row, wearing Malay kebaya outfits and a young girl in a Western dress. Standing behind them are ten men holding musical instruments wearing Malay traditional clothes (baju Melayu) and Malay headpieces (songkok). The instruments they are holding contrast their traditional dress; trumpets, saxophones, a double bass, accordion and drum kit. This image signals the cosmopolitan hybridity of Malay music in the mid-1950s. It also indicates that women were not involved or not depicted as players of musical instruments – they were either singers, dancers, or actresses. In contrast to this, in a section on ‘entertainment centres’, readers will notice pictures of jazz cabaret orchestras posing on their bandstands (pp.32-33). One picture displays eight male musicians in white coats, dark slacks and bowties on a bandstand that displays above them in large letters ‘last dance, tango, quick step, slow foxtrot, waltz, samba, rumba, fast waltz’ (p.33). These words indicate the kind of dances and consequently, the international styles of music that these musicians performed for their patrons; further indication of the cosmopolitan environment of the Singaporean entertainment industry during the 1940s-1960s.

Of the 79 short biographies contained in the book, I will highlight a few interesting personalities rarely mentioned if not only recently emerging in musical scholarship on the Malay Peninsula. The musician ‘biodatas’ are listed in chronological order of the musicians’ birth year. The first musician listed in the biodata section is Khairudin, who was known under his alias, ‘K. Dean’. Born in 1890 of a Cantonese mother and Punjabi father, K. Dean became a prominent bangsawan theatre performer due to his talent as a comedian and a multi-lingual singer, performing to an audience of diverse ethnicities in ‘Cantonese, Punjabi, Malay and English’ (p.52). Aside from forming his own bangsawan troupe in 1932, he also acted in the first Malay-language sound film produced in Singapore, titled ‘Laila Majnun’ (1934, dir. B.S. Rajhans) alongside his wife, Miss. Tijah (p.53).

K. Dean’s wife, also featured in the book, was a famous bangsawan actress, singer and recording artist. She was known for her recording of popular Malay songs such as “Trek Tek Tek” that was later reproduced in the film Sumpah Orang Minyak (1958, dir. P. Ramlee), re-sung by Normadiah (p.57). What can be observed in K. Dean’s and Miss Tijah’s biographies is the extent of musical activity that existed across the region prior to World War Two. Bangsawan practitioners like Miss Tijah – who came from Pontianak in Indonesia – based their careers in Singapore and performed in travelling troupes across Indonesia and the Malay Peninsula. Similar observations can be made of the younger female singer, Momo Latiff who not only had a colourful bangsawan upbringing as a child in Indonesia but was also active as an actress and playback singer in Singapore’s booming Malay film industry in the 1950s (pp.120-121).

Of particular interest are the biographies of musicians and composers that were ‘behind-the-scenes’ in the Malay films of the 1950s to 1960s still popular today. These include the lesser-known film-music composers – aside from P. Ramlee and Zubir Said – such as Osman Ahmad, Yusof B. and Wandly Yazid. Other musicians involved in films include Said Tenor’s musical performance and appearance in numerous releases during the 1950s (pp.140-141) as well as Rahmat Ali’s trumpet playing for P.Ramlee’s famous film-song “Ibu” (p.88-89).

Muzika is a rare gem of a book on music and history in Southeast Asia. While it may not appear to be formatted in the conventions of western scholarship, this book is highly recommended as an earnest, thoroughly researched and personal account of the unknown Malay musicians who made a living as entertainers in Singapore from the early to mid-1900s. It is thus, a rich source of biographical information and photographs that depict the cultural life and social economy of Malay musicians who worked in Singapore during a period spanning the apex of British colonialism, the Japanese occupation and the transition to national independence in the Malay world.

Adil Johan

Adil Johan is a Ph.D. candidate in Music Research

Music Department, Strand Campus, King’s College, London

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 15 (March 2014). The South China Sea