The Future of the Monarchy in Thailand

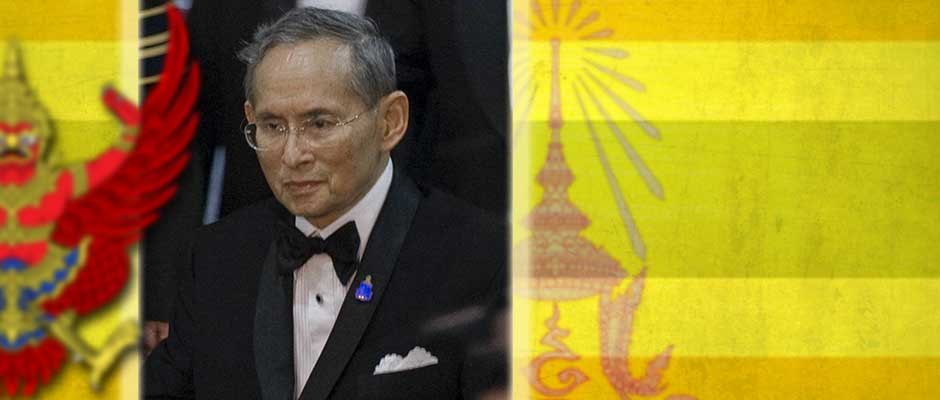

The future of any monarchy is at least partially determined by the strengths and weaknesses of its current reign and the path of succession to the next. This is particularly true in Thailand today where the present King, Bhumibol Adulyadej, is now the longest-reigning living monarch in the world. When coming to the throne in 1946 just fourteen years after the absolute monarchy had been overthrown, the institution of the monarchy had nearly been eclipsed by new political forces. By the 1960s, pro-royalists, allied with the Thai military, succeeded in re-securing the monarchy’s financial base and re-sacralizing the institution. In 1973 and 1992, the King intervened to end military violence against anti-dictatorship protesters, establishing his role as final arbiter in times of crisis.

With the King’s highly publicized trips into rural areas and the myriad royal projects throughout the country dedicated to alleviating rural poverty, the King was perceived as giving his life to the betterment of the people. Contributing to the King’s prestige was his world-record-breaking highest number of honorary degrees, patents for his inventions, and his considerable skill in art, music, and writing. The festivities surrounding the 60th anniversary of the King’s accession to the throne in June 2006 seemed to be the crowning achievement of the reign. Millions of Thai citizens streamed into Bangkok to take part in the celebration. Royal families and foreign dignitaries from around the world descended on Thailand to join in the ceremonies. At the time, the reign King Bhumibol seemed to have secured its legacy.

But the September 2006 military coup that removed the democratically elected and immensely popular government of Thaksin Shinawatra changed everything. The cumulative effect of choices made by the palace over the past four decades suddenly exposed the monarchy. While the King personally enjoys broad support, it is argued here that the monarchy as an institution was at its all time low in terms of both popularity and legitimacy.

How was the legacy of King Bhumibol’s reign so utterly squandered in so few years? The answer tells us much about the future of the monarchy in Thailand. Even without considering the issue of succession, the forces nominally supporting the monarchy have themselves placed the institution into a state of crisis. When the weighty issue of succession is placed upon such a weakened institution, the result might be catastrophic. Whether for better or worse, the long reign of King Bhumibol has come to define the Thai monarchy. Under his reign, a number of internal factors have tended to either strengthen or weaken the long term viability of the monarchy as an institution.

The opening up of the entities related to the monarchy to (relatively speaking) greater public scrutiny has on the whole strengthened the institution. The Privy Council and Crown Property Bureau have granted a certain level of access to scholars, and the palace seemed open to assisting with a new, relatively more balanced biography of the King which even includes a section on the previously taboo subject of lèse-majesté. 1 And while government internet censors routinely block thousands of webpages with content critical of the monarchy, like many of the Wikileaks diplomatic cables on Thailand, they have not blocked, certain critical online publications such as Andrew MacGregor Marshall’s “Thailand’s Moment of Truth.” 2 The government budget has also recently been made accessible online, which includes a certain amount of detail on the allocations made to the royal household and costs of head of state. Although this opening up may have been provoked by outside reports—such as Forbes magazine who listed the King as the world’s richest royal with an estimated “personal wealth” of $30 billion—the resulting dialogue on the whole strengthens the institution.

But on balance the monarchy as an institution has, especially in the last decade, substantially weakened for a number of reasons. First, King Bhumibol as a person has become the embodiment of the Thai throne. Whether this has been due to the mere longevity of his reign or the constant public relations efforts of the palace, the King has successfully become the object of the personality cult. On the downside, the more successfully the King as a person and his good works are portrayed, the weaker the monarchy as an institution becomes. There is no doubt that the King personally is enormously popular. But his personal popularity does not necessarily translate into legitimacy conferred to the institution. In fact, the opposite may be true. It may well be that for many Thais “loyalty to the throne” extends no further than the present reign. The palace succeeded in building up the image of the King’s personal connection to his people, playing up his sacred status, and making the monarchy the spiritual center of the nation. But successes of this type inevitably work against any successor to the throne.

Second, “the palace” is no longer synonymous with “the King.” In the construction of what McCargo has called the “network monarchy”, the King (and palace) intervened directly on a number of occasions, most notably in 1973 and 1992. 3 The King also endorsed at least a half dozen coups between 1957 and 1991. From 1992 to 2005, the network monarchy “refined” its approach, subtly undermining democratic institutions and prime ministers, and portraying the monarchy as “an alternative source of legitimacy to the electoral democracy.” 4 However, ongoing health issues since 2000 reduced the King’s role in the network monarchy. In his absence, “separate centers of influence”, each part of “the palace”, have emerged, as described in this Wikileaks diplomatic cable:

While many observers often refer to the Thai monarchy as if it were a unified, coherent institution, and use “the Palace” as short-hand in the same way “the White House” or “10 Downing Street” is employed as a metaphor for a clearly defined and located nexus of power, neither description is particularly appropriate in the current Thai context.

There are in fact multiple circles of players and influence surrounding the Thai royal family, often times with little overlap but with competing agendas, fueled by years of physical separation and vacillating relationships between principals. Separate centers of influence/players focus around: King Bhumibol; Queen Sirikit; Crown Prince Vajiralongkorn; Princess Sirindhorn; and the Privy Council… 5

If the King was opposed to the 2006 coup, as many sources seem to indicate, he was unable or unwilling to restrain others in the palace who supported it. Most Wikileaks cables indicate that Queen Sirikit and the president of the Privy Council, Prem Tinlasunonda, were the prime movers behind the coup. It was some of the same palace factions that supported demonstrators from the People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD), a movement that tried to obstruct and overthrow an elected government led by Thaksin supporters in 2008. While some argue that the King was pressured by the coup makers to sign off on the coup, such cannot be said of the Queen when she attended the funeral of a PAD protesters killed in clashes with the police.

Third, the unrestrained use of the lèse-majesté law has harmed the monarchy. The law has always limited freedom of expression but at least in the 1990s and early 2000s there were relatively few cases. Europe’s royal families benefit from the frequent polls conducted to measure the public views on their monarchies. The lèse-majesté law makes such public polls impossible. The law has deprived the monarchy of comment and criticism that would help it situate itself more legitimately within the growing democratic environs. On paper, the law protects the king, queen, heir-apparent, and regent but in practice it has seemingly been to protect other members of the royal family as well. Proponents of the law have attempted to extend the protection the law provides to even members of the Privy Council. Anyone can make an accusation, providing a convenient weapon to use against opponents. The law is also notoriously vague and courts have interpreted it broadly. As the law is found in the national security section of the criminal code, basic rights such as bail are routinely denied to those accused. Most disastrously, though, are the heavy sentence and the unprecedented number of cases. The maximum sentence is 15 years for each count, by far the highest anywhere in the world in the past century at least. The number of cases has skyrocketed from an annual average of five between 1992 and 2004, to a high of 478 in 2010. Those suggesting amendment to the law have been forced into exile, physically assaulted, and threatened with death.

Finally, there is another factor that has transformed the political landscape in which the monarchy is situated. The most significant change in the twilight of the present reign has been the deep and pervasive development of political consciousness amongst Thai citizens as a whole. The network monarchy approached the 2006 coup like all past coups in Thai history: the coup is endorsed by the monarchy, the coup makers justify the coup publicly by citing corruption of politicians and threats to the monarchy, an amnesty is given, and then the coup is eventually forgotten.

But a new politically aware citizenry did not forget the coup. The United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD, or “red shirts”) continues to organize to remove the effects of the coup—creating a new more democratic constitution, removing the amnesty clause and prosecuting the coup makers, and reconsidering any legislative or judicial action that led directly from the coup. The movement has given rise to a phenomena known as the Awakening, or eyes having been opened (ta sawang). Through internet networks and by mouth-to-mouth at protests, the Awakened have had their eyes opened to the role of the monarchy and have engaged in full-blown historical and political critiques of the institution. Expressed in coded language to evade arrest, the movement has no illusions about the palace’s repeated attempt to thwart popular sovereignty through the judiciary, the Privy Council, and some members of the royal family.

Rather than forgetting the Queen’s presiding over the funeral of a PAD protester in October 2008—a particularly galling event for red shirts—the newly awakened have christened the day as the “National Day of Awakening.” 6 A royal figure so openly taking sides stripped the palace of any pretence to neutrality. This negative impression was compounded when the monarchy opted not to intervene when red shirts were being killed by government forces in May 2010. More than anything else, the decision to act in 2008 and not to act in 2010, marked the end of the Thai monarchy as it has come to be known. 7 The active involvement of the palace in the coup, the appearance of taking sides by members of the royalty in political conflict, the indiscriminate use of the lese majeste law, and even the awareness of the immense wealth of the throne have all greatly diminished the legitimacy of the monarchy and seriously compromised its future.

But the greatest failure of the Ninth Reign might be the palace’s inability to offer a positive succession scenario. Rather than abdicating—as the King had considered in the late 1980s—and overseeing the transition himself, the King has stayed on. 8 Officially, Prince Vajiralongkorn was designated by the King as crown prince in 1972. But as the King’s health has worsened over the past decade, as efforts to rejuvenate the prince’s image have failed, and as palace infighting has increased, other succession scenarios have emerged. As there has not been a controversial succession within living memory in Thailand, there is a lot of “legal” wiggle room in these scenarios, most involving the Privy Council which might try “to effect a managed transition to the next reign.” 9

If, for instance, the King were to depart the scene, the legal status of the Privy Council and its president are ambiguous. It could be interpreted that Prem automatically becomes the regent upon the King’s death. As regent he could first revise the Succession Law of 1924 in a way that allows the Privy Council to name a different successor—presumably Princess Sirindhorn. Or it might delay forwarding the name of the successor to parliament by calling for an period of mourning of unspecified duration. 10 Or, failing this, a coup might be in order, justified for reasons of national security and the protection of the monarchy. The coup would abolish the parliament and allow the military to effectively name the successor or at least delay the process. Or another scenario may be that the Queen positions herself to be appointed regent by the ailing King and then continues in the position upon his passing.

None of the scenarios lend much legitimacy to the monarchy. The only scenario that has any chance of success is that, following Bhumibol’s wishes, Vajiralongkorn becomes king, adjusts his behavior, takes the opportunity to dismantle the monarchy network and the lèse-majesté law, and reigns in the manner of other constitutional monarchies in the world today. The other scenarios would lead to all-but-certain disasters: any attempts by the Privy Council to alter the King’s choice would further delegitimize the monarchy; any moves that would place Prem or the Queen as the regent would be met with massive opposition and might result in doing away with the monarchy altogether.

At the end of the day, the survival of the monarchy in Thailand will rest upon the question of legitimacy. The present reign has cultivated a set of values and interests that are antithetical to popular sovereignty and out of step with democratic constitutional monarchies in the world. It has consistently undermined democratically elected governments and shown shortsightedness in its public statements and actions. It has supported and endorsed the toppling of democratically elected governments. It has allowed the suppressive lèse-majesté law to be used in its name and it has too closely sided with the extreme agenda of the hyper-royalists. It has so built up the image of the King of the present reign that the successor, by comparison, might find it impossible to succeed. Finally, its improper preparation has made even the question of succession a perilous one, fraught with tempting but dangerous alternatives. In short, it has failed to bring the monarchy into line with the democratic values of a democratic Thailand.

The reign bequeaths to its successor a debilitated and factionalized institution with no clear path on which to continue.

David Streckfuss

Honorary fellow, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 13 (March 2013). Monarchies in Southeast Asia

Notes:

- Nicholas Grossman and Dominic Faulder (editors), King Bhumibol Adulyadej: A Life’s Work (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2012). ↩

- <http://www.zenjournalist.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/thaistory1.1.pdf>. ↩

- Duncan McCargo, “Network Monarchy and Legitimacy Crises”, The Pacific Review, vol. 18, no. 4 (December 2005), p. 501. ↩

- Thongchai Winichakul, “Toppling Democracy”, Journal of Contemporary Asia, vol. 38, no. 1 (February 2008). ↩

- <wikileaks.org/cable/2009/11/09BANGKOK2967.html>. ↩

- Thongchai Winichakul, “The Monarchy and Anti-Monarchy: Two Elephants in the Room of Thai Politics and the State of Denial”, edited by Pavin Chachavalpongpun, in “Good Coup” Gone Bad: Thailand’s Political Developments since Thaksin’s Downfall, (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, forthcoming, 2013), Chapter 4. ↩

- U.S. Ambassador Eric John described the Queen’s action as a “disastrous decision” that was “universally seen as dragging the monarchy, which is supposed to remain above politics, into the partisan fray”, in <wikileaks.org/cable/2009/11/09BANGKOK2967.html>. ↩

- Paul Handley, The King Never Smiles (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), pp. 315-24. ↩

- Michael J. Montesano, “Contextualizing the Pattaya Summit Debacle: Four April Days, Four Thai Pathologies,” Contemporary Southeast Asia, vol. 31, no. 2 (2009), p. 233. ↩

- Shawn W. Crispin, “Thaksin tests Thailand’s deal”, Asia Times, 23 September 2011 <http://www.atimes.com/ atimes/Southeast_Asia/MI23Ae01.html>. ↩