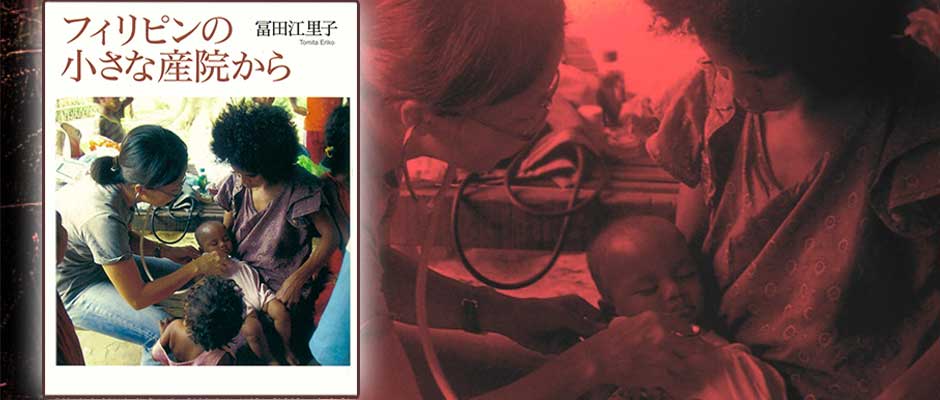

Book Title: 『フィリピンの小さな産院から』(From a Small Maternity Clinic in the Philippines)

Author: 冨田江里子 (TOMITA, Eriko)

Publisher: Tokyo: Seifusha (2012)

“If no medical care exists, can there be births?” This is the main question that Eriko Tomita raises in her work on maternity care in the Philippines. The book is a personal essay of her struggles over a 13 year period in working in a maternity clinic in a Mangahan resettlement in Subic, in the Northwest part of Luzon, the Philippines.

As a qualified nurse and obstetrician in Japan, Tomita learns the practice of maternity clinic in a modern medical care system. The intervention of modern medical technologies that assist childbirth have significantly reduced perinatal mortality and improved the growth rate of premature infants. She understands that while systematized modern medicine technologies have saved the lives of mothers and children exposed to life crises, hospital treatment has prioritized the sense of cleanliness and correctness in controlled environments that exude an “inorganic feeling.” This understanding drove her to look for a certain alternatives in terms of “traditional/ natural” childbirth.

Although Tomita is absorbed by the question of “local wisdom” and practices, her experiences in the field give her a strong standing on the appropriate selection of technologies to aid birth. She is aware of the recurring representations of “wrong behavior based on wrong knowledge” in the Philippines. Far from being a delusional idealist of wanting to “live in another culture,” she maintains an effective treatment with the limited economic freedom her clinic has, as it does not have adequate and regular funds to support modern technologies. Notwithstanding these constraints, she comes to understand the different meanings of cultural practices in the country to provide a holistic childbirth treatment that is locally-based but as effective as those modern technologies can offer.

Aside from the issue of traditional practices of childbirth, Tomita also addresses a number of issues related with her medical experiences in the field. One interesting discussion is about the universality of childbirth in human history. She notes that “whereas the history of medical obstetrics is about 100 years, we have been giving birth for several hundred of thousand years bringing forth the human race.” Childbirth is a process that is a fundamental part of our history and as far as we can predict, will continue to be so. It is a life event everyone has experienced and (many of them) want to experience again in greeting new life. Childbirth depicts the vivid reality of birth as a product of human relationships. It may be complicated and difficult to configure, but it takes the same form of female pregnancy that delivers offspring for the future. This universality of a life event itself makes childbirth different from other kinds of medical care. In its discussion, the book presents several situations where people from different backgrounds became pregnant. It offers the readers a glimpse into the contemporary conditions of our society to acknowledge the potentials of childbirth in human relationships in general.

The practice of development and health care as Tomita concludes is indeed an important issue that constitutes our existence as human race. With its deep reflection and strong description, the book offers a personal narrative on life-cycle episodes that are unique to the Philippines, but is an accessible read for people who don’t know the country.

Shiraishi Natsuko

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 15 (March 2014). The South China Sea